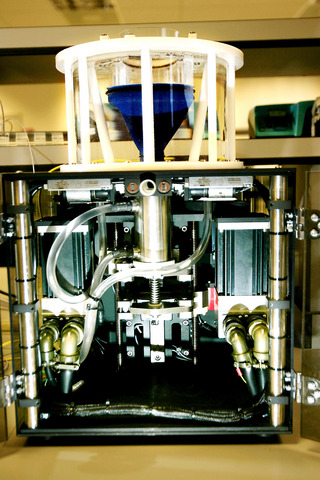

British scientists have built what they say is the world's first artificial stomach: a shiny, high-tech box that physically simulates human digestion.

Constructed from sophisticated plastics and metals able to withstand the corrosive acids and enzymes found in the human gut, the device may ultimately help in the development of super-nutrients, such as obesity-fighting foods that could fool the stomach into thinking it is full.

"There have been lots of jam-jar models of digestion before,'' said Martin Wickham of Norwich's Institute of Food Research, the artificial gut's chief designer, referring to the beakers of enzymes typically used to approximate the chemical reactions in the stomach.

PHOTO: AP

Wickham's patented artificial gut is a two-part model, and is slightly larger than the size of a desktop computer. The top half is a cylinder with a blue funnel, into which food is poured. This is where the food, stomach acids and digestive enzymes are mixed. Once this hydration process is finished, the food gets crunched underneath in a silver metal tube encased in a dark, transparent box. In a real human stomach, the food would then be absorbed by the human body.

Software sets the parameters of the artificial gut — how long food remains in a particular part of the stomach, predicted hormone responses at various stages, and whether it is an infant or adult gut.

Unlike previous gut models, Wickham's model incorporates the physiological elements of digestion, including the stomach contractions that break up food and move it along the assembly line of human digestion.

PHOTO: AP

The artificial gut is already attracting commercial attention.

One company wants to use it to test whether a biscuit can release a specific nutrient in the small intestine. Another group wants to determine if soil contaminants, which could potentially be swallowed by children playing outside, get absorbed by the human body.

The model gut's focus on the physical and chemical reactions that take place in the stomach promises to provide a more detailed understanding of food structure and its impact on digestion.

"This is an important tool that will allow us to understand what happens in the gut, which has essentially been like a black box,'' said Peter Ellis, a biochemistry expert at King's College in London, who was not connected to the project.

Other artificial stomach models have largely neglected the connection between food structure and digestion, according to Ellis.

"This model is important because it gets the science of digestion right," he said.

By understanding how food gets processed in the gut, and in which part of the stomach nutrients get absorbed, researchers may ultimately be able to develop foods designed to manipulate the digestive process, a strategy that would have broad implications for public health.

For instance, knowing how quickly glucose gets absorbed into the bloodstream would potentially help treat diabetes.

"Our knowledge of what actually happens in the gut is still very rudimentary," said Wickham, "but we hope that this model can help fill in some of the blanks."

Some experts say any artificial gut has inherent limitations.

"The stomach is an extraordinarily complex organ, so you cannot create a model that will undertake all of these functions," said Stephen Bloom, head of metabolic medicine at Imperial College in London, who was not involved in the project.

Still, Bloom said that looking at issues such as the breakdown of food and the role of enzymes in a model stomach is valuable.

"There are a number of questions that are very difficult to study in real life that could more easily be answered in the laboratory," he said, explaining that using human volunteers to collect information about digestion is usually a costly and uncomfortable process.

With a capacity about half the size of an actual stomach, the artificial gut can "eat'' roughly 600 milliliters of food, or a normal portion of fish and chips. To date, the most substantial meal it's enjoyed is vegetable soup.

"It's so realistic that it can even vomit," adds Wickham.

The model gut, which was publicly funded, was built at a cost of approximately US$1.8 million. Wickham and his colleagues are currently negotiating with about a dozen companies regarding future projects for the gut.

Aug. 25 to Aug. 31 Although Mr. Lin (林) had been married to his Japanese wife for a decade, their union was never legally recognized — and even their daughter was officially deemed illegitimate. During the first half of Japanese rule in Taiwan, only marriages between Japanese men and Taiwanese women were valid, unless the Taiwanese husband formally joined a Japanese household. In 1920, Lin took his frustrations directly to the Ministry of Home Affairs: “Since Japan took possession of Taiwan, we have obeyed the government’s directives and committed ourselves to breaking old Qing-era customs. Yet ... our marriages remain unrecognized,

During the Metal Ages, prior to the arrival of the Dutch and Chinese, a great shift took place in indigenous material culture. Glass and agate beads, introduced after 400BC, completely replaced Taiwanese nephrite (jade) as the ornamental materials of choice, anthropologist Liu Jiun-Yu (劉俊昱) of the University of Washington wrote in a 2023 article. He added of the island’s modern indigenous peoples: “They are the descendants of prehistoric Formosans but have no nephrite-using cultures.” Moderns squint at that dynamic era of trade and cultural change through the mutually supporting lenses of later settler-colonialism and imperial power, which treated the indigenous as

An attempt to promote friendship between Japan and countries in Africa has transformed into a xenophobic row about migration after inaccurate media reports suggested the scheme would lead to a “flood of immigrants.” The controversy erupted after the Japan International Cooperation Agency, or JICA, said this month it had designated four Japanese cities as “Africa hometowns” for partner countries in Africa: Mozambique, Nigeria, Ghana and Tanzania. The program, announced at the end of an international conference on African development in Yokohama, will involve personnel exchanges and events to foster closer ties between the four regional Japanese cities — Imabari, Kisarazu, Sanjo and

By 1971, heroin and opium use among US troops fighting in Vietnam had reached epidemic proportions, with 42 percent of American servicemen saying they’d tried opioids at least once and around 20 percent claiming some level of addiction, according to the US Department of Defense. Though heroin use by US troops has been little discussed in the context of Taiwan, these and other drugs — produced in part by rogue Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) armies then in Thailand and Myanmar — also spread to US military bases on the island, where soldiers were often stoned or high. American military policeman