The Kasbah du Toubkal, a mountain retreat in the High Atlas outside Marrakesh, is not for the faint of heart or weak of knee. To reach it, you drive up a winding mountain road to the village of Imlil, walk for 20 long minutes up a gravel path, enter a wooden gate and keep walking. But once inside the central garden, you begin to get the point.

Filled with wildflowers, it opens onto a splendid vista — reddish-brown mountains dotted with green walnut groves and boxy mud-brick villages, farmers tending sheep on distant hills, and Mount Toubkal rising snow-capped and gray-blue in the distance.

A spirit of late-onset adventurism had compelled me to make my first trip to Morocco, a country I knew only through the paintings of Matisse; a poster of his Porte de la Casbah, a keyhole arch rendered in blue, hung on my wall for a decade. I've always loved chaotic cities, hidden courtyards and any climate where bougainvillea thrives, but I hadn't thought about hiking until I learned about the Kasbah, which offers day trips and longer hikes from the lodge, complete with a guide, cook and muleteer.

PHOTOS: NY TIMES NEWS SERVICE

When I arrived on a cloudless day in June, my sense of accomplishment was diminished only by a slight pang of guilt, commingled with relief: my luggage had been carried uphill from Imlil — by mule.

The Kasbah calls itself a “Berber hospitality center,” not a hotel. In the brochure, I found this rhetoric self-important; once there, I realized it was entirely accurate. Drinking syrupy sweet mint tea on the terrace, I was a guest; the Berber guides and waiters smoking cigarettes and talking on their cell phones at the low table in the corner were our hosts.

Once the fortified summer palace of a caid, or local governor, the property fell into disrepair after Morocco gained independence in 1956. A British tourism outfit, Discover Ltd., renovated it and opened it to guests in 1995, working in cooperation with local residents, who now run and staff it.

The Kasbah charges a 5 percent levy on rooms and services, which finances a village association that in recent years has bought an ambulance; built a hammam, or communal steam bath, in Imlil; and set up water systems in nearby villages. Martin Scorsese paid to film parts of Kundun, his 1997 movie about the Dalai Lama, at the Kasbah, which used the money to set up a local waste-management system. Discover has since worked with the association to protect the area from rapid development while improving the local economy.

I'm no sucker for eco-tourism boilerplate, but I was impressed by the Kasbah's approach.

I had easily convinced my friend Katja, a historian who lives in Los Angeles, to go along on the trip. The plan was to travel from Marrakesh and spend two nights at the Kasbah's main lodge, then two at its new remote lodge in a nearby Berber village -— which we would reach by trekking 18km over a mountain pass. Neither of us had hiked before, and we hoped our enthusiasm would trump our inexperience.

But first things first.

“Here is the terrace — for relax,” Mustafah, the lodge's doe-eyed steward, said with a shy, friendly smile after we had climbed a steep staircase. In a gesture at once welcoming and proprietary, he stretched his arm across the horizon, toward the cluster of houses in Imlil below, and Mount Toubkal, at 4,165m, the highest of the Atlas Mountains.

For two days, I sat in a canvas chair on that terrace, reading. The sounds of New York slowly dissipated until all I could hear was the “Allahu Akbar” of muezzins echoing across valleys, the occasional crowing of a rooster, the barely perceptible rustle of a faraway waterfall. On the one gray day, clouds enveloped everything beyond a little brown sparrow perched on the terrace railing.

Breakfast and lunch — simple fare like bread with thick local honey and fresh salads — were served on the terrace. Dinner was served in an atmospheric common room with low round tables and Berber carpets. The evening meals — a succulent lamb tagine one night, chicken with green olives the next — began with a ritual hand washing with water poured into a basin from a metal ewer.

The Berbers, or Imazighen as they're called in their own tongue — Berber implies barbarian in Arabic — resisted the Arab conquest of the seventh century and still practice a less rigid form of Islam today. The women we saw all wore bright kerchiefs, not burkas.

The economy is based on subsistence farming, and many Berber men have left Morocco in search of work. Illiteracy is high. I was taken aback when our guide, Lahcen, a moody man in his late 30s with a sensibility more complicated than his culture seemed able to accommodate, deferred to a friend when I asked him to jot his name in my notebook. But he spoke excellent French and decent English, and knew the Toubkal valleys by heart.

Before setting out for the remote lodge, we were handed ski poles to help us keep our footing. Although the trail was never particularly steep, the soft shale sloped gradually on the downhill side, perfect for twisting your ankles. Hiking boots were essential, as were hats and sunscreen. In the hot, dry mountain air, we were comfortable in long cotton pants and long-sleeved T-shirts, but wore sweatshirts on the chillier peaks.

Lahcen carried our large bottle of water in his backpack, along with a cell phone that worked only on the near side of the mountain. He gave us Arabic names, dubbing me Fatima, and Katja Leila. “Ca va, Fatima?” he would say, sometimes holding my hand, as I anxiously made my way along the trail.

The path wound its way through hillsides dotted with clumps of purple and yellow flowers, juniper bushes and a geological formation that looked like melted ice cream. At the top of the first mountain we stopped for lunch — salad with fresh vegetables, bread and cheese, hot mint tea — served to us under a wide tree, at a low table set with a golden cloth. We felt awkwardly pampered.

Toward the end of the six-hour trek, I was nearly hallucinating from the exertion. Finally, somehow, we reached our destination: the village of Id Issa in the Azzadene Valley, where electricity arrived only last year. From the dusty road I looked up at the remote lodge, a lovely pink stone house atop the town's highest hill. It was worth the final push. Our bathroom had a big marble tub and plenty of hot running water, heated by solar panels on the roof. I took a long shower, drank several liters of water and fell into a deep sleep.

When I woke up a few hours later, no one was around. From the terrace, I watched the sun setting pink over the rusty mountains. I followed voices downstairs to the compact kitchen. There, perched on square stools around a low table, were several men playing cards — and Katja.

“Hi,” she said cheerily. “Meet Omar, Omar, Omar, Omar and Hossein.”

While I napped, Katja had conducted a dissertation's worth of anthropological research, with Lahcen translating from Berber into French. Omar the cook had a 6-day-old baby; Omar Rouge, with the red jacket, stood guard outside the house overnight, Omar Vert, with the beguiling green eyes, was finishing the garden terrace (the lodge opened only in April), and Omar the young steward, whose black vest inspired us to call him Omar Noir, had a pregnant 16-year-old wife.

Omar Noir's mother had brought some delicious flatbread, and tomorrow we could visit her to see how she bakes it.

In the center of the hardscrabble village, Omar Noir's house was a cluster of mud-brick boxes stacked into the hillside, with a satellite dish on the terrace. His mother had a warm smile and several gold teeth. Her kitchen was a dark, igloo-shaped room with a small hole in the ceiling for ventilation. One exposed bulb hung on the wall. Rabbits scampered on the mud floor. They're good to eat during Ramadan, when food is scarce, Lahcen explained.

While Omar's luminous little sisters looked on, his mother pushed flat slabs of dough onto the inner walls of a low kiln. They quickly developed crackly black bubbles, like nan. The bread was chewy and crisp and delicious, and it occurred to me that women like Omar's mother had been baking it the same way for thousands of years. The recent arrival of electricity and running water had barely changed their daily lives.

A skinny man in his early 20s with a moustache of adolescent fuzz, Omar Noir spoke little French and less English, but was a physical comic to rival Chaplin. That evening, wearing a white waiter's jacket, he set a heavy tray of dishes on the dining table with an exaggerated sigh, then slumped down on the couch feigning exhaustion, as if to say: “You saw that my house has dirt floors. Why should I even bother with the farce of Cordon Bleu service?”

After dinner, Lahcen and the Omars sang call-and-response songs, drumming a rhythm on pots and pans. Sometimes, they lined up in a row and shimmied their shoulders in a dance. The songs were about courtship and love and the end of childhood friendships, and had no harmonies.

After three days in the mountains, Katja had developed blisters so raw that she couldn't hike back to the main lodge, even on a more direct three-and-a-half-hour route. And so, while I trudged along, she was carried most of the way by mule, a veritable Berber princess.

We walked the familiar stretch from Imlil to the Kasbah in slow motion, then soothed our aches in the hammam. In our absence, a new crop of guests had gathered on the terrace, some of them day-trippers from Marrakesh, 64km away. Greenhorns, we thought to ourselves, with the snobbery of the newly initiated. After our journey to the village and back, we felt like family.

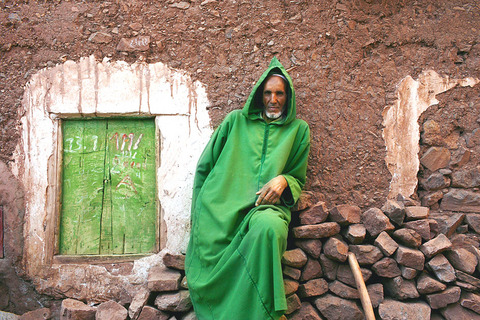

After the calm of the Atlas, Marrakesh was a blur — mopeds, mules and labyrinthine souks with kilims and spices, men in long robes and yellow pointy-toed slippers, little girls playing hopscotch in alleyways at dusk, the vast main square filled with snake charmers like a Delacroix painting come to life — and everything baked in an intense dry heat that gloriously saps you of all ambition.

On our last evening in Morocco, we ate well and drank crisp sauvignon blanc. The restaurant had white tablecloths, fish knives and elegant waiters. Our sandals still had traces of Atlas Mountain dust. We felt as if we'd traversed a thousand years of human development in one long day.

We took one look at the disastrously translated menu — “vinaigrette of tomatoes believed” was my favorite, “cru” meaning both cooked and believed in French — and began to laugh uncontrollably.

We were exhausted, and oddly despondent. The restaurant was fine — excellent, really — only nothing was right. We didn't want whitefish carpaccio and frisee salad with toasted chevre. We wanted the bread baked by Omar's mother in a house with one faucet — 80km and several centuries away.

GETTING THERE

Royal Air Maroc, British Airways and Air France are among a number of airlines that fly to Marrakesh, often via Casablanca, but sometimes through European cities.

Imlil, where the Kasbah du Toubkal is situated, is about 64km south of Marrakesh, or about an hour-and-a-half by car on a winding and sometimes dirt road; it is a five-hour drive from Casablanca. The lodge can arrange a car to Imlil from downtown Marrakesh or the airport; the cost is 800 dirhams a car, about US$88. Taxis from Marrakesh are generally cheaper, but be prepared to bargain. Rental cars are available at Moroccan airports and major cities.

ACCOMMODATIONS

The Kasbah -- altitude 1,799m -- has eight hotel-style rooms, three private houses, a luxury suite and several dormitory-style rooms with a shared bath. Starting in November, prices range from US$45 for a spot in a dormitory-style room, to US$935 for a separate house with three bedrooms.

The remote lodge in Id Issa has three double rooms with baths, each US$250 a night, with breakfast and dinner. Next year, the Kasbah plans to open a second lodge in another valley. See www.kasbahdutoubkal.com for more information.

WHEN TO GO

High season for trekking is April to October, when the snow has mostly melted from the mountains. Nights are cool, even in summer, but the air is dry and the sun warm. Temperatures can reach 32 degrees Celsius in August and drop to -3 degrees Celsius at night in December, with the most moderate weather in late spring and early fall

May 26 to June 1 When the Qing Dynasty first took control over many parts of Taiwan in 1684, it roughly continued the Kingdom of Tungning’s administrative borders (see below), setting up one prefecture and three counties. The actual area of control covered today’s Chiayi, Tainan and Kaohsiung. The administrative center was in Taiwan Prefecture, in today’s Tainan. But as Han settlement expanded and due to rebellions and other international incidents, the administrative units became more complex. By the time Taiwan became a province of the Qing in 1887, there were three prefectures, eleven counties, three subprefectures and one directly-administered prefecture, with

It’s an enormous dome of colorful glass, something between the Sistine Chapel and a Marc Chagall fresco. And yet, it’s just a subway station. Formosa Boulevard is the heart of Kaohsiung’s mass transit system. In metro terms, it’s modest: the only transfer station in a network with just two lines. But it’s a landmark nonetheless: a civic space that serves as much more than a point of transit. On a hot Sunday, the corridors and vast halls are filled with a market selling everything from second-hand clothes to toys and house decorations. It’s just one of the many events the station hosts,

Among Thailand’s Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) villages, a certain rivalry exists between Arunothai, the largest of these villages, and Mae Salong, which is currently the most prosperous. Historically, the rivalry stems from a split in KMT military factions in the early 1960s, which divided command and opium territories after Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石) cut off open support in 1961 due to international pressure (see part two, “The KMT opium lords of the Golden Triangle,” on May 20). But today this rivalry manifests as a different kind of split, with Arunothai leading a pro-China faction and Mae Salong staunchly aligned to Taiwan.

Two moves show Taichung Mayor Lu Shiow-yen (盧秀燕) is gunning for Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) party chair and the 2028 presidential election. Technically, these are not yet “officially” official, but by the rules of Taiwan politics, she is now on the dance floor. Earlier this month Lu confirmed in an interview in Japan’s Nikkei that she was considering running for KMT chair. This is not new news, but according to reports from her camp she previously was still considering the case for and against running. By choosing a respected, international news outlet, she declared it to the world. While the outside world