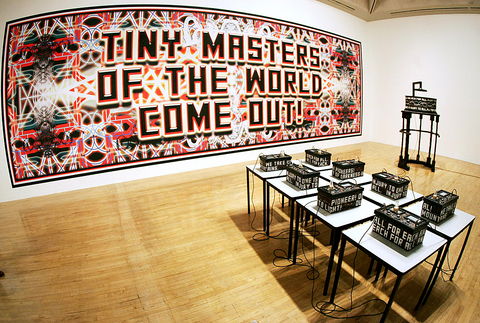

Weird and incomprehensible objects, machines of unknown purpose, mystifying slogans and unprovable propositions: it must be Turner prize time again. All of the above, and much more, are to be found in Mark Titchner's peculiar arrangements of the mechanical and the hand-chiseled, the computer-animated and the mechanically challenged.

Titchner quotes Nietzsche and the biblical exhortations of trade union banners; he dabbles in phenomenology and new age nonsense — and I haven't the faintest idea what he is on about, or why he does what he does, the way he does. Titchner's optical art discs, whose pattern is borrowed from Roger Dean's original design for the Vertigo record label, revolve on their stands with an eccentric, mesmerizing wobble. Watching them turn, one is reminded of early Bridget Riley, of Marcel Duchamp's rotoreliefs and of a trillion teenage acid trips. TV monitors flare with strobe lighting, and dates taken from a Liberty human rights audit flash back at me. There are throbbing, animated Rorschach blots, a clackety racket of machinery and a deeper sonorous hum, tuned to the wavelength of the human brain.

It's like that scene in The Ipcress File, when the bad guys try to drive Michael Caine around the bend. Without a doubt, Titchner is trying to brainwash me. Critical resistance is futile. He will win the Turner prize. He is the best. Give him the money. He is the Master. I will obey.

PHOTOS: AGENCIES

The best I can say about Titchner's work is that it looks bizarre. There's the hand-carved wooden tree-thing-cum-hat-stand surmounted by a wooden model of a crystal, wired up to a heavy-handed Victorian pulpit-like object nearby, which is in turn connected to a number of boxes reminiscent of car batteries, each of which has on it a little jar containing the sawdust collected when Titchner carved the phrases emblazoned on their sides. There must be those who take Titchner's willful obscurantism for creative thinking and artistic depth, but his appeal passes me by. It's all too clever by half, I keep thinking: too many complications, too much self-conscious eccentricity.

The aesthetic is grim. Is this the kind of ugliness that we later come to see as beauty? It's the sort of question Rebecca Warren's sculpture raises. Warren has been nominated partly on the basis of her contribution to the recent Tate Triennial. Soon, artists will be nominated for the Turner prize on the strength of their previous Turner prize nominations. This is a much better show for the sculptor. I must confess to being bored by her Robert Crumb-meets-Willem de Kooning-meets-Helmut Newton big-arsed and -breasted clay floozies. Why must she always make a joke out of her sculptures?

What I like best here are her great globbery inchoate clay lumps. They bulge and seethe with life — nascent ears, tongues, orifices, nipples. They remind me of some of Lucio Fontana's sculpture.

In her deliberately scrappy, wall-mounted vitrines, Warren is beginning to go somewhere new. Inevitably, one thinks of Beuys's vitrines, of Richard Tuttle and a number of other artists. In these stage-set like interiors, populated with furry pompoms, mounds of clay planted with sticks, scraps of woodshavings, twigs, twisted bits of glowing neon, and odds and ends as seemingly inconsequential as a cherry pit and a single human hair, Warren manages to build up a strange and tense portentousness.

One work is called Sylvesternacht. Does she mean us to think of David Sylvester, whose best writing was on Giacometti? The work consists of two wall-mounted vitrines. Among other things, both contain large spheres. Is this meant to be the rotund Sylvester, hanging around in a studio or gallery?

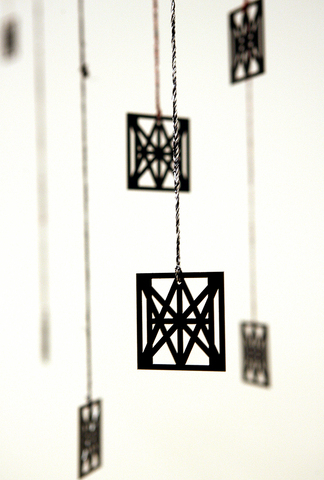

Being comprehensible isn't everything. Art is not always there to be understood. Who knows what all the elements in Rebecca Warren's vitrines signify, or what, exactly, Tomma Abts means by what she paints? Abts shows 11 paintings here, all identically sized, all completed in the past six years. Each presents something like a spatial conundrum, with impossible perspectives and folds, inconsistent shadows and highlights, baffling geometries and unreadable progressions.

What is Abts painting, and what do her paintings allude to? Each is an event on a plane. You don't look at Abts' paintings, so much as observe them. Each is a foreign country, bounded by a vertically orientated 48cm by 38cm canvas. Sometimes the surface is marked with canals or walls, or has the appearance of scored and folded papers, struggling to achieve three dimensions. Some are reminiscent of the kinds of swirls one can only ever see in polarized light, their outlines as frozen as metal inlay in enamel.

Abts' paintings are somehow being produced at the wrong time, and belong to an alternative parallel history of modernism. She has spoken of wanting to make paintings that belong in the future. People talk about experiencing art in the here and now: hers exists at a tangent to the present, in an unspecifiable there and then. This, in part, is what is so good about them.

Some paintings depict a kind of imaginary space — inside the drawer of an old desk, the folds of a patterned handkerchief in a pocket. One thinks of wooden marquetry, of crumpled cellophane, of targets, unknown semaphores and flags. Why are these paintings so memorable? I think it is because of their evident conviction, the restraint and reserve with which each is delivered. Every painting is unmistakably by its author, each quite unlike its neighbor. The world Abts depicts is utterly consistent, even with all its anomalies and flaws.

Phil Collins was short listed for this year's Deutsche Borse photography prize, and his presence there struck me as something of a category error. Collins uses photography, and is concerned very much with what happens to people when they have a camera pointed at them, but he is not — at least not in a way I find interesting — a photographer; he's a filmmaker. Encountering his work for the first time, people might confuse his Turner prize show for the work of Kutlug Ataman, who was short listed two years ago (and not simply because Collins's subjects here are Turkish, as is Ataman, although that compounds the problem).

Collins' The Return of the Real (gertcegin geri donusu), originally commissioned for the 2005 Istanbul Biennial, consists of a number of interviews, each about an hour long. Because of a technical glitch during my visit, only one interview was being replayed, over and over. Cajoled into marrying a stranger on a reality TV show, Meral (“I marry a lot, so I'm used to divorcing a lot!”) told her life story — her abusive father, her psychotic brother, her many mistaken marriages. I was so fascinated with this damaged woman's story, I completely forgot it was meant to be part of an artwork in the Turner prize.

A second version of Return of the Real is in production in Bilbao, and Collins plans a third with British participants. He has built a fully functioning office within the Turner prize show at the Tate, called shady lane productions and staffed five days a week.

There may well be those who feel their lives have been ruined by their participation in the Turner prize, which itself includes a modicum of television exposure. Will the Turner contenders be queuing, in the full gaze of visitors to the show, to tell the stories of their ruin for Collins's project, after the winner is announced? Who should win anyway? Who is making the best art, and what does that mean nowadays? Abts and Collins are the most developed in my view. I think Collins has made more concise and telling works elsewhere. Abts' quiet and disturbing paintings seem utterly right and unexpected. They ought to win.

June 2 to June 8 Taiwan’s woodcutters believe that if they see even one speck of red in their cooked rice, no matter how small, an accident is going to happen. Peng Chin-tian (彭錦田) swears that this has proven to be true at every stop during his decades-long career in the logging industry. Along with mining, timber harvesting was once considered the most dangerous profession in Taiwan. Not only were mishaps common during all stages of processing, it was difficult to transport the injured to get medical treatment. Many died during the arduous journey. Peng recounts some of his accidents in

“Why does Taiwan identity decline?”a group of researchers lead by University of Nevada political scientist Austin Wang (王宏恩) asked in a recent paper. After all, it is not difficult to explain the rise in Taiwanese identity after the early 1990s. But no model predicted its decline during the 2016-2018 period, they say. After testing various alternative explanations, Wang et al argue that the fall-off in Taiwanese identity during that period is related to voter hedging based on the performance of the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP). Since the DPP is perceived as the guardian of Taiwan identity, when it performs well,

The Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) on May 18 held a rally in Taichung to mark the anniversary of President William Lai’s (賴清德) inauguration on May 20. The title of the rally could be loosely translated to “May 18 recall fraudulent goods” (518退貨ㄌㄨㄚˋ!). Unlike in English, where the terms are the same, “recall” (退貨) in this context refers to product recalls due to damaged, defective or fraudulent merchandise, not the political recalls (罷免) currently dominating the headlines. I attended the rally to determine if the impression was correct that the TPP under party Chairman Huang Kuo-Chang (黃國昌) had little of a

At Computex 2025, Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang (黃仁勳) urged the government to subsidize AI. “All schools in Taiwan must integrate AI into their curricula,” he declared. A few months earlier, he said, “If I were a student today, I’d immediately start using tools like ChatGPT, Gemini Pro and Grok to learn, write and accelerate my thinking.” Huang sees the AI-bullet train leaving the station. And as one of its drivers, he’s worried about youth not getting on board — bad for their careers, and bad for his workforce. As a semiconductor supply-chain powerhouse and AI hub wannabe, Taiwan is seeing