It is not often that a great power vanishes into thin air overnight, but that is exactly what happened to Prussia. With the stroke of a pen, a state that had stood at the center of European politics for centuries was abruptly ordered off the stage of history, dismissed as “a bearer of militarism and reaction in Germany” by Law No. 46 of the Allied Control Council, signed on Feb. 25, 1947.

Few tears were shed. But Iron Kingdom, Christopher Clark's stately, authoritative history of Prussia from its humble beginnings to its ignominious end, presents a much more complicated and compelling picture of the German state, which is too often reduced to a caricature of spiked helmets and polished boots. Prussia and its army were inseparable, but Prussia was also renowned for its efficient, incorruptible civil service; its innovative system of social services; its religious tolerance; and its unrivaled education system, a model for the rest of Germany and the world. This, too, was Prussia — a tormented kingdom that, like a tragic hero, was brought down by the very qualities that raised it up.

Clark, a senior lecturer in modern European history at Cambridge University, does an exemplary job. A lively writer, he organizes masses of material in orderly fashion, clearly establishing his main themes and pausing at crucial junctures to recapitulate and reconsider. Prussia, a self-invented artifact right down to its name, demands the kind of careful demythologizing that it receives from Clark, who gently but insistently exposes the flaws in most of the received wisdom about his subject. A result is an illuminating, profoundly satisfying work of history, brightened by vivid character sketches of the principals in his drama.

To take just one example of many, Clark challenges the notion that Frederick William I (1713-40) achieved what one 19th-century Prussian historian called “the perfection of absolutism.” While it is true, Clark acknowledges, that Frederick curbed the power of the nobility and from Berlin imposed centralized rule over the region known as the Mark Brandenburg, posterity has greatly exaggerated the power of the nascent Prussian state, whose officials numbered not more than a few hundred men.

“Official documents passed to their destinations through the hands of pastors, vergers, innkeepers, and schoolchildren who happened by,” Clark writes. In one principality, an investigation found that most government communications took up to 10 days to travel just a few kilometers, partly because their first stop was the local tavern, where they were unsealed, passed around and discussed over glasses of brandy, finally arriving at their destinations, in the words of investigators, “so dirtied with grease, butter or tar that one shudders to touch them.” The supposedly well-oiled machine of Prussian absolutism squeaked and creaked, especially in the hinterlands.

The myth of Prussian militarism, likewise, receives careful scrutiny. A large, disciplined army transformed the Mark Brandenburg, with its poor soil, scant natural resources, and lack of access to the sea, into a regional power. But the militarization of society did not really begin until the late 19th century, and even then Clark questions whether the Prussian experience set it apart from the rest of Europe. France and Britain were equally committed to empire-building and military might. “The ‘civility’ and anti-militarism of British society were perhaps more a matter of self-perception than a faithful representation of reality,” he writes. “It is also worth noting that the German peace movement developed on a scale unparalleled elsewhere.”

Similarly, in the 1930s conservative Prussian landowners provided the Nazis with widespread enthusiastic support, but most of the officers who plotted against Hitler came from the Prussian officer corps. Prussia, under the Social Democrat Otto Braun and his police chief, Albert Grzesinski, was a stronghold of democracy in the days leading up to the Nazi assumption of power, and Braun, in his own way, epitomized the Prussian ideal.

“His endless appetite for work, his fastidious attention to detail, his dislike of posturing and his profound sense of the nobility of state service were all attributes from the conventional catalog of Prussian virtues,” Clark writes.

Prussian problems and flaws were acute, intractable and ultimately fatal. If geography is destiny, Prussia was doomed from the start. Surrounded by hostile powers, it could secure its future only by acquiring territory, but each acquisition created new, troubled borders, which fed the appetite for conquest.

Under rulers like Frederick William (the Great Elector, 1640-88) and Frederick the Great (1740-86), the modest state of Brandenburg played a weak hand brilliantly, selling its favors to the highest bidder, fighting or remaining neutral as self-interest demanded, arranging advantageous dynastic marriages and gradually acquiring coveted parcels of territory, including the Duchy of Prussia.

There could be no happy ending to Prussia's restless ambitions, driven by a profound sense of insecurity that deepened with German unification. A patched-together kingdom assumed primacy within a patched-together country.

“There was an unsettling sense that what had so swiftly been put together could also be undone, that the empire might never acquire the political or cultural cohesion to safeguard itself against fragmentation from within,” Clark writes. Deep-seated fears of encirclement by hostile powers, a purely Prussian obsession, he writes, found expression in military planning that called for lightning offensives against France and Russia.

Perhaps most dangerous, Prussia's security depended on an army that had never been subject to civilian control. It was, Clark writes, “a praetorian guard under the personal command of the king.”

This, he adds, was “Prussia's most fateful legacy to the new Germany.” And, he might have added, to the rest of the world.

May 26 to June 1 When the Qing Dynasty first took control over many parts of Taiwan in 1684, it roughly continued the Kingdom of Tungning’s administrative borders (see below), setting up one prefecture and three counties. The actual area of control covered today’s Chiayi, Tainan and Kaohsiung. The administrative center was in Taiwan Prefecture, in today’s Tainan. But as Han settlement expanded and due to rebellions and other international incidents, the administrative units became more complex. By the time Taiwan became a province of the Qing in 1887, there were three prefectures, eleven counties, three subprefectures and one directly-administered prefecture, with

President William Lai (賴清德) yesterday delivered an address marking the first anniversary of his presidency. In the speech, Lai affirmed Taiwan’s global role in technology, trade and security. He announced economic and national security initiatives, and emphasized democratic values and cross-party cooperation. The following is the full text of his speech: Yesterday, outside of Beida Elementary School in New Taipei City’s Sanxia District (三峽), there was a major traffic accident that, sadly, claimed several lives and resulted in multiple injuries. The Executive Yuan immediately formed a task force, and last night I personally visited the victims in hospital. Central government agencies and the

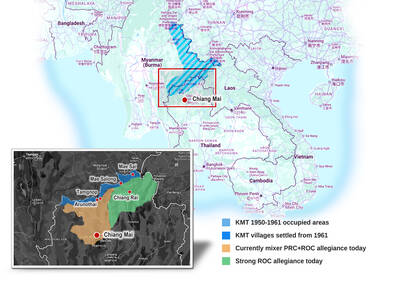

Among Thailand’s Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) villages, a certain rivalry exists between Arunothai, the largest of these villages, and Mae Salong, which is currently the most prosperous. Historically, the rivalry stems from a split in KMT military factions in the early 1960s, which divided command and opium territories after Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石) cut off open support in 1961 due to international pressure (see part two, “The KMT opium lords of the Golden Triangle,” on May 20). But today this rivalry manifests as a different kind of split, with Arunothai leading a pro-China faction and Mae Salong staunchly aligned to Taiwan.

As with most of northern Thailand’s Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) settlements, the village of Arunothai was only given a Thai name once the Thai government began in the 1970s to assert control over the border region and initiate a decades-long process of political integration. The village’s original name, bestowed by its Yunnanese founders when they first settled the valley in the late 1960s, was a Chinese name, Dagudi (大谷地), which literally translates as “a place for threshing rice.” At that time, these village founders did not know how permanent their settlement would be. Most of Arunothai’s first generation were soldiers