To the anti-spam researchers at Message-Labs, an e-mail filtering company, each new wave of a recent stock-pumping spam seemed like a personal affront.

The spammers were trying to circumvent the world's junk-mail filters by embedding their messages -- whether peddling something called China Digital Media for US$1.71 a share, or a "Hot Pick!" company called GroFeed for just US$0.10 -- into images.

In some ways, it was a desperate move. The images made the messages much bulkier than simple text messages, so the spammers were using more bandwidth to churn out fewer spams. But they also knew that, to filters scanning for telltale spam words in the text of e-mail messages, a picture of the words "Hot Stox!!" is significantly different from the words themselves.

PHOTO: NY TIMES NEWS SERVICE

So the bulk e-mailers behind this campaign seemed to calculate that they had a good chance of slipping their stock pitches past spam defenses to land in the in-boxes of

prospective customers.

It worked, but only briefly. Anti-spam developers at MessageLabs, one of several companies that essentially reroute their clients' e-mail traffic through proprietary spam-

PHOTO: NY TIMES NEWS SERVICE

scrubbing servers before delivering it, quickly developed a "checksum," or fingerprint, for the images, and created a filter to block them.

Advances in spam-catching techniques mean that most computer users no longer face the paralyzing crush of junk messages that began threatening the very utility of e-mail communications just a few years ago.

But spammers have hardly given up, and as they improve and adapt their techniques, network managers must still face down the pill-pushers, get-rich-quick artists and others who use billions of unwanted e-mail messages to troll for income. "For the end user, spam isn't that much of a problem anymore," said Matt Sergeant, MessageLabs' senior anti-spam technologist. "But for the network, and for people like us, it definitely is."

PHOTO: NY TIMES NEWS SERVICE

Shortly after MessageLabs created a filter to catch the stock spams, the images they

contained changed again.

They were now arriving with what looked to the naked eye like a gray border. Zooming in, however, the MessageLabs team discovered that the border was made up of thousands of randomly ordered dots. Indeed, every message in that particular spam campaign was generated with a new image of the border -- each with its own random array of dots.

"That was kind of cool and kind of funny," said Sergeant, a soft-spoken British transplant who spends his days helping to douse spam fires from his home office outside Toronto.

During a recent meeting at the company's New York office, in Midtown Manhattan,

Sergeant and a colleague, Nick Johnson, an anti-spam developer visiting from Message-Labs' headquarters in Gloucester, England, expressed both amusement and respect over the sheer creativity of the world's most

prolific spammers, who continue to dump hundreds of millions of junk messages into the e-mail stream each day.

"It was almost like they knew what we were doing," Sergeant said.

Several surveys -- from AOL, the Pew Internet and American Life Project and others -- have indicated that the amount of spam reaching consumer in-boxes has at least stabilized.

That is true for users whose networks are protected by off-site, third-party filtering

services like MessageLabs', as well as those protected by network software or in-house equipment that filters messages before they hit a company's e-mail server.

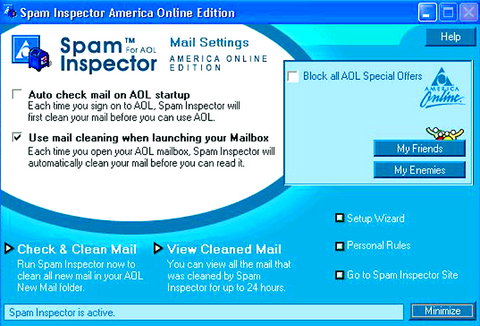

If individual users also have personal spam filters installed on their computers, their in-box spam count can be reduced to a trickle.

But spam continues to account for roughly 70 percent of e-mail messages on the Internet, despite tough anti-spam laws across the globe (including the Can-Spam Act in the US), despite vigorous lawsuits against individual junk-mail senders and despite the famous prediction, by Bill Gates at the World Economic Forum in 2004, that spam would be eradicated by this year.

The continuing defiance of spammers was demonstrated last week when one of them forced Blue Security, an anti-spam company based in Israel, to shut down its services. The company gave customers the power to enact mob justice on spammers by overloading them with requests to be removed from mailing lists.

A spammer in Russia retaliated by knocking out Blue Security's Web site and threatening virus attacks against its customers. Blue

Security said it would back off rather than be responsible for a "cyberwar."

A PLATEAU IN GROWTH

While there are some indications that the growth rate of spam has reached a plateau or even slowed, experts say spikes are always looming. That is partly because spammers can hide themselves or their operations in

countries where law enforcement is lax, like Russia, Eastern Europe, China and Nigeria.

Because some spammers can churn out 200 million or more messages a day, and because less than 1 percent of those need to elicit responses from naive, click-happy users to turn handsome profits, there is little incentive to stop.

"That's really just the daily battle," said

Sergeant, who routinely shares intelligence on individual spammers with other anti-spam

organizations, and with the FBI and other law enforcement agencies. "That 1 percent is the wall, really; it's the spammers creating something new that we just haven't seen before. And for us it's a matter of how quickly we can deal with it."

There is plenty to deal with. Most spam is still just, well, spam: low-rent pitches for stocks and penis-enlargement pills. But there are also the more immediate menaces, including attempts to trick consumers into giving up bank and credit card information or the use of spam to deliver viruses and other malicious software.

From an industry perspective, anti-virus and anti-spam scanning are virtually inseparable, and MessageLabs is among many companies jockeying to position themselves as full-service contractors, offering to filter, scan, scrub and archive both incoming and outgoing mail.

It's a lucrative strategy.

IDC, the research firm, estimates that the global market for "messaging security" will grow to US$2.6 billion by 2009, from US$675 million last year. The category consists mostly of anti-spam services, but also covers outbound filtering -- something that employers now demand and all vendors include, said Brian Burke, an IDC analyst.

IDC estimates that the larger market for "secure content management," which folds in virus protection, Web filtering and spyware protection, will grow to US$11.4 billion by 2009 from US$4.8 billion last year.

This year, about 60 percent of businesses were using software to combat spam, with the rest split between using managed services and anti-spam hardware, according to Osterman Research, which conducts market analysis on the messaging industry. But the percentage of businesses moving to managed services is expected to double, to almost 40 percent, during the next two years.

In that context, it may not be surprising that Microsoft recently acquired FrontBridge, the third-largest provider of managed e-mail

services. MessageLabs and Postini, based in San Carlos, California, have long been the leaders in the category.

While much growth in this field will be driven by the threat of viruses and other bugs attached to messages, the wave of simple but inventive marketing spam remains a big

concern, and, in many ways, is the harder thing to catch. Consider the stock spam using random dots in the borders.

"We actually developed some technology to detect borders in images and figure out the entropy -- that is, to figure out if the border was random," Sergeant said. "So that was fine." Of course, shortly afterward, "they decided to stop using the borders," he added.

From there, the senders began placing a small number of barely perceptible and, again, randomly placed dots -- a pink one here, a blue one there, a green one near the bottom -- throughout the images. Then they shifted to multiple images, with words spelled partially in plain text and partially as images, so that the content, when viewed on a common e-mail reader like Outlook or AOL, would look like an ordinary message.

"There are loads of different kinds of obfuscation," Johnson said. "They've realized that people are looking for V1agra spelled with a '1' and st0ck with a `zero' and that sort of thing, so they might try some sort of meaning obfuscation, like just referring to a watch as a `wrist accessory' or something like that. So they say something like, `Drape your wrist with this elegant accessory.'

"Any way not to say `Rolex,'" he added, "so it's quite cryptic."

HTML TRICKS AND ZOMBIE BOTS

Johnson described another trick that a spammer had recently deployed so that messages peddling Viagra would move into recipients' in-boxes.

By default, most modern e-mail software can display messages that are written with the same text formatting code used to create Web pages -- known as hypertext markup language, or HTML. Like viewers of Web pages, e-mail users never actually see the underlying code, or "tags" used to make some words appear, say, bold or italicized. But spam filters scan this code, too, looking for "spammy behavior," as Johnson put it.

In this instance, a clever spam writer

slipped a Viagra message past many filters by spelling the word with several I's, then using HTML code to shove all of the I's together. "Whenever you view this in your e-mail

program," Johnson said, "the letter spacing is set to minus-3 pixels, so it will show all these I's on top of each other, and it will look like one I.

"That was quite an impressive one, actually," he said.

And vexing, Sergeant added. Without a

special rule created by the team, it would have been virtually impossible for a machine to

examine the source code of a message and determine that this was the word "Viagra."

"The word appears on screen as it should," Sergeant said. "But if you actually are examining the HTML, you just couldn't pull out a word from it. So while a computer can't figure out what the words are in the e-mail, the human eyes can."

A company like MessageLabs tries to avoid examining messages at this level. Instead, it prefers to stop much of the junk at the door, using what is called IP blocking. This prevents the receipt of messages from a particular Internet protocol address already identified as a spamming source.

This technique is sometimes frowned upon by Internet purists, because it can punish innocent users by blacklisting a whole range of addresses from a single host. But Sergeant said IP blocking had become more refined since the early days of spam fighting. "It's very, very important to us," he said. "It's our first line of defense, really."

Still, spammers can often get around this by turning to zombie bots. These are vast networks of personal computers that have been surreptitiously infected with malicious software, permitting a spammer to use their computing power, without the owners'

knowledge, to spew or relay spam, viruses, keyloggers, phony "update your bank account" messages and other dark payloads.

Zombies now deliver half to three-quarters of spam, according to a US Federal Trade Commission report to Congress in December on the state of the spam problem. Among the zombies' many advantages is an ever-shifting collection of IP addresses.

TELLTALE INTRODUCTION

Messagelabs' filtering database tries to discover new zombie bots by studying the behavior of e-mail messages from new addresses. Normally, for instance, a machine looking to deliver a message to another machine essentially says "hello" by passing an identifying string of code. Most legitimate mail servers will say "hello" with the same string over and over, for every message.

"When a machine communicates with us in two, three, four different ways within a small time frame," Sergeant said, "that makes the sending machine look kind of weird." That behavior can indicate "it's not a real machine, it's just one of these drone armies."

Some low-end spamming software, too, may leave characteristic fingerprints -- for instance, the telltale way in which it forges the header information on e-mails -- that spam fighters gradually add to their cumulative anti-spam wisdom.

For all the algorithmic derring-do, however, sooner or later the game turns not on IP addresses or software fingerprints, but on the content of the message. It's the approach that MessageLabs researchers like least, but one that spammers constantly force on them.

Nigerian e-mail scams are a particular nuisance in this regard. Familiar to any e-mail user, these are the ones seeking an advance payment from the recipient to help rescue a deposed prince or to collect a percentage on some elaborately portrayed fortune. They are difficult to weed out because the senders often use Web-based e-mail services like Yahoo or Gmail, so IP blocking is impractical.

The language used in the e-mail messages, too, is often common enough that no particular string lends itself to safe rule-making; the risk of filtering out legitimate communications would be high.

MessageLabs has spent a year compiling a database, Scam DNA, of 15,000 Nigerian scam messages, and used pattern analysis to build a family tree of the scams. It has found that most of the pitches are derived among a few hundred templates.

"Scam DNA basically codifies this into an algorithm," Sergeant said, "where, hopefully, we can detect this going on and find new scams based on the old scams."

But even if it works, the amount of spam it would eliminate from the overall deluge of junk mail would be negligible by almost any measure, and Sergeant and his team will still be forced into encounters with "Cialis" and "st0x" and "Viiiiagra."

Following the shock complete failure of all the recall votes against Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) lawmakers on July 26, pan-blue supporters and the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) were giddy with victory. A notable exception was KMT Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫), who knew better. At a press conference on July 29, he bowed deeply in gratitude to the voters and said the recalls were “not about which party won or lost, but were a great victory for the Taiwanese voters.” The entire recall process was a disaster for both the KMT and the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP). The only bright spot for

Water management is one of the most powerful forces shaping modern Taiwan’s landscapes and politics. Many of Taiwan’s township and county boundaries are defined by watersheds. The current course of the mighty Jhuoshuei River (濁水溪) was largely established by Japanese embankment building during the 1918-1923 period. Taoyuan is dotted with ponds constructed by settlers from China during the Qing period. Countless local civic actions have been driven by opposition to water projects. Last week something like 2,600mm of rain fell on southern Taiwan in seven days, peaking at over 2,800mm in Duona (多納) in Kaohsiung’s Maolin District (茂林), according to

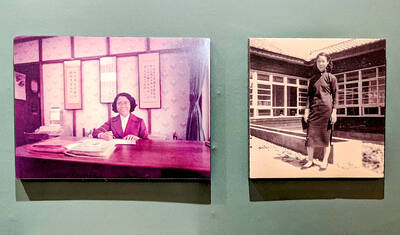

Aug. 11 to Aug. 17 Those who never heard of architect Hsiu Tse-lan (修澤蘭) must have seen her work — on the reverse of the NT$100 bill is the Yangmingshan Zhongshan Hall (陽明山中山樓). Then-president Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石) reportedly hand-picked her for the job and gave her just 13 months to complete it in time for the centennial of Republic of China founder Sun Yat-sen’s birth on Nov. 12, 1966. Another landmark project is Garden City (花園新城) in New Taipei City’s Sindian District (新店) — Taiwan’s first mountainside planned community, which Hsiu initiated in 1968. She was involved in every stage, from selecting

The latest edition of the Japan-Taiwan Fruit Festival took place in Kaohsiung on July 26 and 27. During the weekend, the dockside in front of the iconic Music Center was full of food stalls, and a stage welcomed performers. After the French-themed festival earlier in the summer, this is another example of Kaohsiung’s efforts to make the city more international. The event was originally initiated by the Japan-Taiwan Exchange Association in 2022. The goal was “to commemorate [the association’s] 50th anniversary and further strengthen the longstanding friendship between Japan and Taiwan,” says Kaohsiung Director-General of International Affairs Chang Yen-ching (張硯卿). “The first two editions