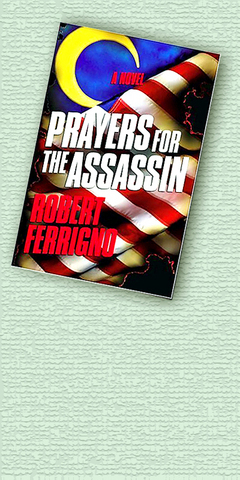

Robert Ferrigno's Prayers for the Assassin is a futuristic fantasy that puts an Orwellian nation, the Islamic Republic, where the United States of America used to be. The author does not treat this as a pleasant prospect. He imagines a 2040 in which New York and Washington are gone, Mecca is radioactive, Mount Rushmore has been eradicated and the aircraft carrier Ronald Reagan has been renamed for Osama bin Laden. Super Bowl cheerleaders are men. Barbie's got a burqa. At least Starbucks prices aren't much higher than they used to be.

The book is a thriller, and in some ways a surprisingly common-place one. But Ferrigno has given serious thought to his hypothetical scenario. He tries to envision the complexities of daily life in a world where all the rules have changed -- except in the Bible Belt, which has become a Christian refuge. In the Muslim nation, the black robes enforce religious laws and goats' heads are delicacies at butcher shops. Amusement-park attractions include AK-47s and suicide belts for children. Popular songs deliver constructive moral lessons. Needless to say, nobody draws political cartoons.

These aspects of the book are by far its most involving. Ferrigno has done his best to take an outline of Islam and morph it with US tradition, catalyzing these changes with a whiff of nuclear war. And since he is not on a suicide mission, he takes care to note that many Muslims in the new regime are good citizens, reasonable people both modern and moderate. They are wary of funda-mentalism, and they tolerate anything-goes zones where strict religious rules of behavior are suspended. Las Vegas remains ground zero for forbidden games.

While the book's background exerts a grim sci-fi fascination, its central story manages to be surprisingly ordinary. Even in this radically altered future, heroes and villains and romantics behave pretty much as expected. Declar-ations of love sound the same, even if threats have a new ring. ("I'm gonna snap your neck so fast you'll be rolling in perfumed virgins before you know you're dead.") And a chase is a chase, even if the leading man is a skilled fedayeen fighter and the bad guy, an assassin pointedly named Darwin, is on his trail. Throughout the book, from hidden lairs to corridors of power, the same quaint, melodramatic command is heard: Find the girl.

The girl is the feisty young historian Sarah Dougan, daughter of the new regime's first and most famous martyr. She is an influential scholar. Also, in a pinch, she can stick a chopstick in a rapist's eye. Dougan is the author of "How the West Was Really Won," a study of debased popular culture in pre-Islamic US. It is Dougan's contention, as well as Ferrigno's, that the seeds of destruction can be seen in the US' present-day reverence for celebrities, extreme tastes in pornography and across-the-board decadence. "They were so free, so unencumbered by morality, that they craved chains," one character says about the late 20th century.

Ferrigno has a cautionary message to deliver, and Dougan is his mouthpiece. Despite "the supple harlotry of her limbs" and her by-the-numbers love affair with Rakkim Epps, the book's hero, Dougan is on a serious mission. History states that the dire nuclear events of 2015 and subsequent US political upheaval were a result of a Zionist plot. As a consequence of this claim, American Jews have taken refuge in Canada and Russia. Israel has been destroyed. Dougan questions that version of events.

She is writing a second book called "The Zionist Betrayal?" Lest readers miss the point, Ferrigno writes, "that question mark had made all the difference."

Needless to say, a lot of people wish Dougan would shut up. The US' conversion was neatly expedited by both civil war and by public pronouncements from Hollywood, where converting to Islam became all the rage. (The book's denouement manages to feature the Academy Awards.) But Dougan has a conspiracy theory and she is out to prove it. That angle, plus the wild-card status of China in Ferrigno's imaginary geopolitics, ought to give Prayers for the Assassin a vigorous plot, but the book still manages to move slowly. It screeches to a halt whenever Dougan and Epps take a lovebird break.

The story's momentum is not helped when the same hollow threats are repeated over and over. A sinister powermonger known as the Old One sits in his lavish 90th-story Las Vegas apartment, scheming predictable schemes. Redbeard, the noble and powerful security chief who raised both Dougan and Epps, continues to voice the same worries about their welfare. Darwin smirks and taunts in lively fashion. ("Well, look at you. Aren't you the tenacious lawman.") But even he overstays his welcome. The book's wild stabs at novelty yield a scene of bleak depravity. Formerly known as "the happiest place on earth," Disney-land is now full of so-called rent-wives, whose services can be engaged very briefly, then terminated by improvised Muslim divorce.

Prayers for the Assassin weakens its ingenuity with cliched thriller touches. Still, it has enough novelty to attract attention and enough substance to be genuinely frightening. "The nuclear attack merely toppled a rotten tree," the Old One intones.

Ferrigno propounds the rotten-tree theory and also appreciates Islam's power to persuade. "Muslims were the only people with a clear plan and a helping hand," one character explains, "and everyone was equal in the eyes of Allah. That's what they said, anyway."

A note on product placement: in the Islamic Republic, the sanctioned drink is Jihad Cola. Nobody likes it. And Coca-Cola has become much-coveted contra-band. "Who could imagine something this good would be illegal?" Epps wonders. Somebody in advertising could imagine it more easily than somebody truly interested in the future.

As we live longer, our risk of cognitive impairment is increasing. How can we delay the onset of symptoms? Do we have to give up every indulgence or can small changes make a difference? We asked neurologists for tips on how to keep our brains healthy for life. TAKE CARE OF YOUR HEALTH “All of the sensible things that apply to bodily health apply to brain health,” says Suzanne O’Sullivan, a consultant in neurology at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery in London, and the author of The Age of Diagnosis. “When you’re 20, you can get away with absolute

When the South Vietnamese capital of Saigon fell to the North Vietnamese forces 50 years ago this week, it prompted a mass exodus of some 2 million people — hundreds of thousands fleeing perilously on small boats across open water to escape the communist regime. Many ultimately settled in Southern California’s Orange County in an area now known as “Little Saigon,” not far from Marine Corps Base Camp Pendleton, where the first refugees were airlifted upon reaching the US. The diaspora now also has significant populations in Virginia, Texas and Washington state, as well as in countries including France and Australia.

On April 17, Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫) launched a bold campaign to revive and revitalize the KMT base by calling for an impromptu rally at the Taipei prosecutor’s offices to protest recent arrests of KMT recall campaigners over allegations of forgery and fraud involving signatures of dead voters. The protest had no time to apply for permits and was illegal, but that played into the sense of opposition grievance at alleged weaponization of the judiciary by the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) to “annihilate” the opposition parties. Blamed for faltering recall campaigns and faced with a KMT chair

A police station in the historic sailors’ quarter of the Belgian port of Antwerp is surrounded by sex workers’ neon-lit red-light windows. The station in the Villa Tinto complex is a symbol of the push to make sex work safer in Belgium, which boasts some of Europe’s most liberal laws — although there are still widespread abuses and exploitation. Since December, Belgium’s sex workers can access legal protections and labor rights, such as paid leave, like any other profession. They welcome the changes. “I’m not a victim, I chose to work here and I like what I’m doing,” said Kiana, 32, as she