Over a year had slipped by since I first landed in Singapore and cycled through Malaysia, Thailand, Cambodia, Vietnam and Laos. Rust had eaten into my once-proud-looking mountain bike and the cobwebs were setting in, reminding me that the time had come once again to swap the concrete confines of Bangkok for the wide open road.

I chose Thailand's northernmost province of Chiang Rai as the next destination for a mountain bike tour. It offered a mountainous landscape and a turbulent political history, besides adjoining the porous borders of Burma to the north and Laos to the east. Besides which, the mist-shrouded mountains near Chiang Rai are still referred to by tour operators, with a deliberate air of mystery, as "The Golden Triangle."

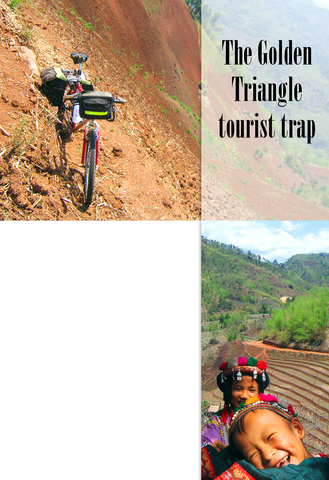

I was keen, firstly, to get off the beaten track, and secondly to explore the region unencumbered and free of tour guides. Thus it was that a few kilometers out of Chiang Rai I found myself swinging off the road, down a mud track and into the woods.

PHOTOS: BEN HOPKINS, TAIPEI TIMES

For the first two nights the villages I stopped in were Akha and Lisu hill tribe settlements. The hill tribes of this region are semi-nomadic and each tribe has a dialect which differs from Thai, rendering my phrase-book useless. Their customs, mode of dress, spiritual beliefs and, I imagined, cuisine were unique to themselves.

Instead, instant noodles from the nearest 7-Eleven (only half a day's walk away) are generously served up, indicating the modern world is fast encroaching upon these charming and friendly people.

The following night, however, in a Lisu village, I'm offered a feast that includes birds and squirrels, all roasted on an open fire beneath a brilliantly luminous sky that now seems light years away from the modern world.

After three days tracing my way through the tribal paths of the Chiang Rai region, I emerge at the foot of a 13km climb to Mae Salong. The road up the mountain offers breathtaking views and as I near the top the sinking sun illuminates my guest house like a shining palace set against a darkening skyline.

My wake-up call comes courtesy of an American. As I poke my head through the shutters of my guest house, he immediately spots me and hollers, "What are ya doin' here man? Come down to breakfast!"

My new buddy introduces himself with a bone-crushing handshake as Rambo and before I have a chance to order coffee plummets into a speech about the dangers that lurk in the hills above Chiang Rai.

"The government wants you to believe it's safe up here, but it's not."

"What's not safe?" I ask.

"Man, ya don't know? They're still growing poppies and shooting anyone who goes near. Nothing's changed since '79. Everyone knows it but no one dares speak out. Everyone's in business with them drug lords. You'd better just stick to the road."

Until some years ago, Chiang Rai was reputedly Thailand's major producer of opium. But, as a result of a military crackdown and a crop-substitution program, the trade has been successfully pushed over the border. I decide to explore this so-called lawless region for myself.

The town of Mae Salong straddles a 1,800m-high hilltop and every open space offers a vista of green rolling hills rich with tea plantations. The town was founded by Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) soldiers led by general Tuan Shiwen from southern China who refused to surrender when the communists finally gained power in 1949.

Originally on their way to Burma, these KMT soldiers and their families were later forced across the border into Thailand in 1961 by a Burmese government eager to appease their Chinese neighbors to the north. Many of them therefore settled in Mae Salong and formed a Yunnanese community in the Thai kingdom.

Opium was reputedly one of the main sources of income for Mae Salong until the mid-1980s. Then a road was built linking the town with the outside world and creating easy access for the Thai military.

There are no signs of the dangers that Rambo spoke of. The cool climate and dramatic surroundings complemented the relaxed atmosphere of the town. Shops were well stocked with local produce such as tea, coffee, dried mushrooms and fruit wrapped in fancy packaging. Old men with wispy beards sit in the shop fronts sipping tea while the women serve up Chinese cuisine and the kids play as if there was no tomorrow.

By the following morning I'm on the road from Mae Salong to Mae Sai, which roller-coasts over some of the steepest hills I've ever climbed. The heat soars, and the thick humid air has sweat seeping out of me, as from a perforated teabag.

Thailand's northernmost town of Mae Sae is 70km north of Mae Salong and straddles the border with Burma, and shops and stalls stacked with produce sneaked across the frontier river are sold there at remarkably cheap prices.

Most of the guest houses in Mae Sai run alongside this river. Taking an early evening stroll up to the water's edge, I focus my camera on the other side. Before I have a chance to click I'm grabbed by a Thai. On the other side a handful of men are shouting and waving their arms. Later I learn the spot where I attempted to take the photo is a section of the river where Burmese cross the border and then return home every night. Gunmen on both sides guard it, and the produce coming over is the subject of many legends.

The town of Mae Sai, so colorful and alive with activity during the day, takes on a bleak and eerie chill once night falls. People stay indoors; most of the bars and restaurants close, and the streets become the domain of the reputed smugglers. The only places that appear to be busy are the massage-parlors that service them.

The next day, under a sun that's been peeling the skin off the back of my neck I pull up in a small village called Sop Ruak, the official center of the Golden Triangle. It's located where Laos, Burma and Thailand merge at the confluence of the Ruak and Mekong rivers.

Tempting as it is to invent sightings of one-eyed bandits boiling vats of opium in forests where intoxicated monkeys fall from the trees, the sad truth is the adventure quota here is next to zero.

Tourism has replaced opium as the local source of gold. There's the Golden Triangle Souvenir Shop and the Golden Triangle Restaurant. It really is time to re-name the place The Golden Triangle Tourist Trap.

For the following two days I follow the burnt ochre mud-tracks away from the heart of the Golden Triangle back to Chiang Rai and the point where I started the tour.

The following evening, sore from sunburn, I'm refueling in a restaurant when suddenly someone wallops me on the shoulder.

"Hey man, ya made it back in one piece!"

It's Rambo, who pretty much followed the same route I took, only where I saw old ladies picking tea he saw heavily-armed outlaws leading convoys of smugglers through the forests to the border.

"So then, did ya see 'em?" he asks.

We share a pizza and drink some beer, toasting our respective adventures like two Vietnam veterans.

KLM flies from Taipei to Bangkok daily for a return fare of around NT$8,000. There is an overnight train from Bangkok to Chiang Mai, and Chiang Rai is a short bus journey from there.

On April 26, The Lancet published a letter from two doctors at Taichung-based China Medical University Hospital (CMUH) warning that “Taiwan’s Health Care System is on the Brink of Collapse.” The authors said that “Years of policy inaction and mismanagement of resources have led to the National Health Insurance system operating under unsustainable conditions.” The pushback was immediate. Errors in the paper were quickly identified and publicized, to discredit the authors (the hospital apologized). CNA reported that CMUH said the letter described Taiwan in 2021 as having 62 nurses per 10,000 people, when the correct number was 78 nurses per 10,000

As we live longer, our risk of cognitive impairment is increasing. How can we delay the onset of symptoms? Do we have to give up every indulgence or can small changes make a difference? We asked neurologists for tips on how to keep our brains healthy for life. TAKE CARE OF YOUR HEALTH “All of the sensible things that apply to bodily health apply to brain health,” says Suzanne O’Sullivan, a consultant in neurology at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery in London, and the author of The Age of Diagnosis. “When you’re 20, you can get away with absolute

May 5 to May 11 What started out as friction between Taiwanese students at Taichung First High School and a Japanese head cook escalated dramatically over the first two weeks of May 1927. It began on April 30 when the cook’s wife knew that lotus starch used in that night’s dinner had rat feces in it, but failed to inform staff until the meal was already prepared. The students believed that her silence was intentional, and filed a complaint. The school’s Japanese administrators sided with the cook’s family, dismissing the students as troublemakers and clamping down on their freedoms — with

As Donald Trump’s executive order in March led to the shuttering of Voice of America (VOA) — the global broadcaster whose roots date back to the fight against Nazi propaganda — he quickly attracted support from figures not used to aligning themselves with any US administration. Trump had ordered the US Agency for Global Media, the federal agency that funds VOA and other groups promoting independent journalism overseas, to be “eliminated to the maximum extent consistent with applicable law.” The decision suddenly halted programming in 49 languages to more than 425 million people. In Moscow, Margarita Simonyan, the hardline editor-in-chief of the