Oh, to have been a fly on the wall when Blair Tindall discussed her new tell-it-all with legal counsel!

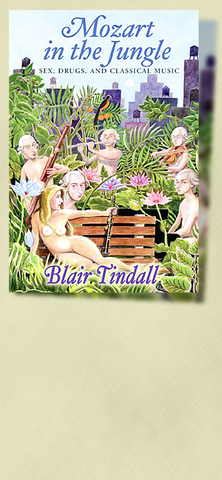

In Mozart in the Jungle: Sex, Drugs and Classical Music the oboist-turned-journalist chronicles her life as a freelance musician in New York City with a candor meant to set tongues clucking.

Tindall spares almost no one in her tale of indulgence and career advancement. Characterizations are so unflattering and frequently scandalous, she had to use 13 pseudonyms.

In her accounting, the North Carolina School for the Arts, where she attended high school in the mid-1970s, was a merry-go-round of sexually manipulative classmates, bingeing ballet students and rapacious faculty members. She sold baggies of pot there and then used her "dope profits" to buy a ticket to hear violinist Itzhak

Perlman.

For her, the New York freelance world was an arena of drunks and druggies. "I'd tried working my way into the coke scene since drug use had become a way of networking with the top freelancers."

Then there was the play-for-pay. After recounting a night with the conductor of a touring Broadway show, she pauses to ask, "Why, I thought, did I bother with an answering machine? Between Sam (Sanders, a well-known accompanist) and my former oboist boyfriends, I got hired for most of my gigs in bed."

As for her catalog of the sexual styles of specific types of instrumentalists, you'll need to turn to page 70. Tindall names Keith Lockhart, conductor of the Boston Pops Orchestra, as one of her sex partners. In a statement reported by Boston newspapers, Lockhart denied any relationship beyond friendship.

In a similar vein, Tindall relates taking drugs and falling into bed with the oboist "Jimmy," who, she says, took a job at the Houston Symphony in 1984. Houston Symphony principal oboist Robert Atherholt joined the orchestra that year after working in the New York orchestras she mentions. Reached by us, Atherholt said, "I'm not the Jimmy described in the book."

Though there are parallels to his career, he said, "what she says in the book is an absolute fabrication." He added, "The reality was that she wasn't that good a player."

Tindall begins her story with a visit to a seedy apartment where students are snorting cocaine while listening to Wagner's Ring Cycle. "How did classical music ever bring me to this place?" she asks.

"Young and inexperienced, I wanted this in-crowd of classical musicians to accept me so I would be asked to play with them in the city's hottest orchestras and chamber music groups" -- even though, at age 22 and four years into her life in New York, she already was substituting with the New York Philharmonic.

By the time Tindall arrives at this point in her story, it's clear that she's anything but young and inexperienced. At 14, she was drinking with older men and sneaking tokes on the loading dock of the music store where she worked. And so on through the years as a boarding-school student and as an undergraduate at the Manhattan School of Music.

For housing in New York, she chose the Allendale, an old, run-down apartment house stocked with musicians like herself. During the 21 years she lived there, they ranged from wide- and wild-eyed college students to well-known performers to aging musicians trapped in a life that Tindall depicts as sad.

She soon started getting freelance jobs and settled into a hectic pace, juggling romances with hustling jobs and playing with such prestigious ensembles as the Orpheus Chamber Orchestra and the St. Luke's Orchestra. As jobs in classical music became scarcer around 1990, she turned to playing in orchestra pits on Broadway.

Along the way, she indulged in a lot of behavior typical of the late 1970s and 1980s. By the mid-1980s, when "Jimmy" was ready to leave for Houston, Tindall writes that she was involved with "three of the city's most powerful oboists, each of whom could make or break my career."

"My scenario with these men had felt like wildly romantic fantasy, as if I were starring in a film about the music business. Now it was turning into a bad dream that affected my livelihood."

She saw one of them while at a concert in Carnegie Hall with Jimmy. Looking across the balcony, "I saw a rush of understanding in Jayson's eyes. He turned away. He had finally realized why I toured with Orpheus and he did not."

In return, "Jayson would never again hire me for his studio dates. Other oboists would penalize me for the work Jimmy had provided me and denied them, and I wouldn't play with Orpheus or in Randy's pit again for some time."

On the surface, she was successful. By 1999, she was earning US$82,000 a year and had health insurance, pension contributions and a flexible schedule. But she was also deeply unhappy. That year, she left New York to study journalism at Stanford University.

What happened?

Tindall burned out. She dreamed of getting a full-time job with a symphony orchestra but never got past the first stage of endless auditions. With that, many people can sympathize.

Annoyingly, though, Tindall offers little sense of recognizing her own limitations as a musician. She relates cockily playing a wrong note three times during an audition -- even after a member of the audition committee suggested she look hard at the music. That slip doesn't suggest the perception and attentiveness necessary for a top-notch professional career.

On April 26, The Lancet published a letter from two doctors at Taichung-based China Medical University Hospital (CMUH) warning that “Taiwan’s Health Care System is on the Brink of Collapse.” The authors said that “Years of policy inaction and mismanagement of resources have led to the National Health Insurance system operating under unsustainable conditions.” The pushback was immediate. Errors in the paper were quickly identified and publicized, to discredit the authors (the hospital apologized). CNA reported that CMUH said the letter described Taiwan in 2021 as having 62 nurses per 10,000 people, when the correct number was 78 nurses per 10,000

As we live longer, our risk of cognitive impairment is increasing. How can we delay the onset of symptoms? Do we have to give up every indulgence or can small changes make a difference? We asked neurologists for tips on how to keep our brains healthy for life. TAKE CARE OF YOUR HEALTH “All of the sensible things that apply to bodily health apply to brain health,” says Suzanne O’Sullivan, a consultant in neurology at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery in London, and the author of The Age of Diagnosis. “When you’re 20, you can get away with absolute

May 5 to May 11 What started out as friction between Taiwanese students at Taichung First High School and a Japanese head cook escalated dramatically over the first two weeks of May 1927. It began on April 30 when the cook’s wife knew that lotus starch used in that night’s dinner had rat feces in it, but failed to inform staff until the meal was already prepared. The students believed that her silence was intentional, and filed a complaint. The school’s Japanese administrators sided with the cook’s family, dismissing the students as troublemakers and clamping down on their freedoms — with

As Donald Trump’s executive order in March led to the shuttering of Voice of America (VOA) — the global broadcaster whose roots date back to the fight against Nazi propaganda — he quickly attracted support from figures not used to aligning themselves with any US administration. Trump had ordered the US Agency for Global Media, the federal agency that funds VOA and other groups promoting independent journalism overseas, to be “eliminated to the maximum extent consistent with applicable law.” The decision suddenly halted programming in 49 languages to more than 425 million people. In Moscow, Margarita Simonyan, the hardline editor-in-chief of the