The FBI doesn't like it. The Department of Homeland Security in the US is so concerned that it has closed down Web sites related to it. The Moving Picture Association of America (MPAA) is waging a war against it. And every day millions of people around the world use it to share music, TV programs and movies.

The "it" is BitTorrent -- a computer program that's the brainchild of the softly-spoken Bram Cohen. It is a super-smart way to share huge files over the Internet, and one which, depending on whose side of the argument you listen to, is either an evil tool for those involved with copyright theft, or a work of genius set to transform the media industry as we know it.

Recent research has shown that last year BitTorrent was responsible for one third of all traffic on the Internet. That's one third. And this despite a wave of legal activity against the peer-to- peer technology (P2P) that un-derpins Cohen's brainchild.

PHOTO: NY TIMES

In essence, BitTorrent is just the latest in a line of programs that started with Napster and allows individuals to swap information with each other over the internet. An Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development report on digital music released this week revealed that at any one time there are as many as 10 million people exchanging files using all forms of P2P. Business Week has estimated that the total number of users could be as high as 100 million.

BitTorrent has become more popular than its competition because it is much more efficient. Systems such as Napster and Kazaa often used to grind to a halt because the files that were being shared sat on one computer and could only be downloaded as quickly as the lines going in and out of that computer would allow.

Cohen's idea was to break the files up into bits. Once someone downloaded a bit, they also became a source for that bit. As a result, more people downloading a file meant there were also more people uploading it, which meant it actually became faster rather than slower.

Originally intended for software developers to move their work around the net, it wasn't long before BitTorrent became popular with music and video fans. This shouldn't have come as much of a surprise: Instead of people simply swapping songs of around 3-4 megabytes, using BitTorrent they could swap whole movies of about 500 times bigger (1.5 gigabytes).

And swap they do. Anything and everything digital is shared. Legal and illegal. People gather on sites where they can download files or "torrents," which they then run on their own computer using special software. If you have a broadband connection and can set it all up (and you need to be reasonably technically competent to do so), you can download an album in an hour, an hour's worth of TV in a couple of hours; and a movie overnight.

Needless to say, the advent of torrent sharing is not making the movie industry happy -- and, like the recording industry before it, the response is lawsuit-shaped.

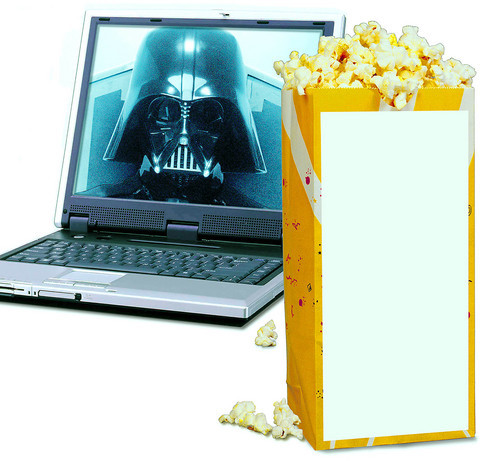

The Motion Picture Association of America -- the organization that has been most vehemently against the growth of BitTorrent -- has, until now, focused its attention not on BitTorrent itself, but on sites that allow the downloading of torrents. One such site was EliteTorrents.org. It was here that around 100 movies and the final instalment of Star Wars: Revenge of the Sith, appeared -- six hours before it was due to open in US cinemas. On May 28, officers from the FBI swooped on a number of homes and offices across the US in what was called operation D-Elite. Within hours, the site was no more.

If you go to EliteTorrents.org today, you will find that its sleek grey design is replaced by the logos of the FBI and the US Department of Homeland Security alongside a bold announcement: "This site has been permanently shut down by the Federal Bureau of Investigation and US Immigration and Customs Enforcement. Individuals involved in the operation and use of the Elite Torrents network are under investigation for criminal copyright infringement."

Dan Glickman the president of the MPAA declared the closure of EliteTorrents was "bad news for internet movie thieves and good news for preserving the magic of the movies."

It's fair to say that the movie industry is rarely first in line for a sympathy vote. It claims that piracy costs it US$3.5 billion a year, a figure that doesn't include the losses from internet file sharing. However, the very thing that lays behind the dramatic increase in piracy -- the arrival of the DVD -- has also brought the industry some quite spectacular dividends. The DVD market in the US last year was worth US$21.2 billion, with the retail market alone up year on year by 33 per cent. And it continues to grow every year.

The precise impact of P2P on sales is also a moot point. While the industry believes it has a detrimental effect, this week's report from the OECD on digital music admitted that "digital piracy may be an important impediment to the success of legitimate online content markets" but "it is difficult to establish a basis to prove a causal relationship between the 20 percent fall in overall revenues experienced by the music industry between 1999 and 2003."

The other debate is whether BitTorrent itself (and, by extension, Cohen) is responsible for piracy. No one is arguing whether or not copyright infringement happens, but whether by banning the software that allows it you are also stifling a new and exci-ting technology.

At the moment, the US Supreme Court is making its mind up in the case of MGM vs. Grokster -- where the issue is whether a piece of software itself can be held responsible for the piracy that is committed using it.

The landmark case in this area goes back to 1984 when the movie industry tried to kill off the video recorder. The defen-dant back then was Sony which now, as a studio owner, finds itself on the other side of the divide. Whatever develops in the courts, it is clear that BitTorrent offers much more than movie piracy; it might change the future of TV too.

Last week, on the heels of the recall election that turned out so badly for Taiwan, came the news that US President Donald Trump had blocked the transit of President William Lai (賴清德) through the US on his way to Latin America. A few days later the international media reported that in June a scheduled visit by Minister of National Defense Wellington Koo (顧立雄) for high level meetings was canceled by the US after China’s President Xi Jinping (習近平) asked Trump to curb US engagement with Taiwan during a June phone call. The cancellation of Lai’s transit was a gaudy

Following the shock complete failure of all the recall votes against Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) lawmakers on July 26, pan-blue supporters and the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) were giddy with victory. A notable exception was KMT Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫), who knew better. At a press conference on July 29, he bowed deeply in gratitude to the voters and said the recalls were “not about which party won or lost, but were a great victory for the Taiwanese voters.” The entire recall process was a disaster for both the KMT and the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP). The only bright spot for

From Godzilla’s fiery atomic breath to post-apocalyptic anime and harrowing depictions of radiation sickness, the influence of the nuclear bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki runs deep in Japanese popular culture. In the 80 years since the World War II attacks, stories of destruction and mutation have been fused with fears around natural disasters and, more recently, the Fukushima crisis. Classic manga and anime series Astro Boy is called “Mighty Atom” in Japanese, while city-leveling explosions loom large in other titles such as Akira, Neon Genesis Evangelion and Attack on Titan. “Living through tremendous pain” and overcoming trauma is a recurrent theme in Japan’s

As last month dawned, the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) was in a good position. The recall campaigns had strong momentum, polling showed many Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) lawmakers at risk of recall and even the KMT was bracing for losing seats while facing a tsunami of voter fraud investigations. Polling pointed to some of the recalls being a lock for victory. Though in most districts the majority was against recalling their lawmaker, among voters “definitely” planning to vote, there were double-digit margins in favor of recall in at least five districts, with three districts near or above 20 percent in