Three Kings may not be the only movie about the Gulf War, but it can still claim to be the first movie that tried to present Operation Desert Storm for what it was: an exercise in confused motivations, undecided objectives and media-fuelled political paranoia. And since director David Russell spent some US$48 million dollars of Warner Bros' money bringing Three Kings into existence, the movie also has some claim to being the most anti-American studio movie of its generation.

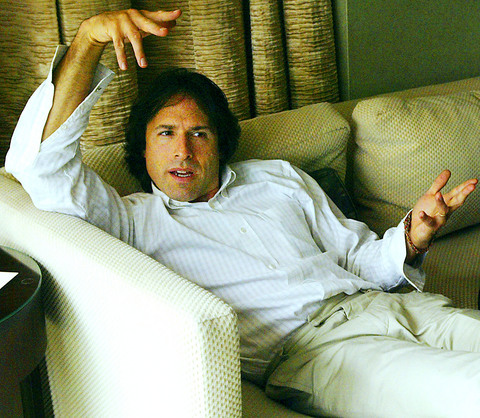

At first sight, Russell cuts an unlikely figure as the standard-bearer of Hollywood agit-prop. He's the kind of person who thinks before he speaks, who's wary of being dragged into much-ploughed side-issues. He's also the very model of concise expression when a point demands it.

This last quality, clearly, is what persuaded Warner Bros that Russell could hack it in the big leagues when he took on the project.

PHOTO: AP

"When they welcomed me, I couldn't believe they would let me do anything," he recalled. "You may remember Warner Bros had just had a terrible two years. They'd done all these franchise movies -- Lethal Weapon 4 and Batman and Robin -- and all their movies had a certain flavor to them. The New York Times business section ran a piece that encouraged them to step up and start using more independent filmmakers. Three Kings is now perceived as a new archetype: an independent-minded studio picture. I think it's seen as a hybrid. It was way too big to be a boutique independent film; it's not exactly the paint-by-numbers commercial film; it's somewhere in the middle."

Three Kings was undoubtedly a unique proposition. Russell harnessed all the slash-and-burn tropes of the modern war movie, creating expansive firefights, injecting pitch-black humor wherever feasible, and unleashing unambiguous disapproval of presidential foreign policy in the wake of Operation Desert Storm.

As it happens, the political content of Three Kings was perfectly in keeping with Russell's pre-filmmaking career. A literature and political-science student in the early 1980s, Russell spent four months teaching in Nicaragua as the Contra insurgency gathered steam. Back in the US, he continued working with immigrants before turning to documentary-making at the Smithsonian

Institute.

Russell isn't a firebrand, exactly -- just an astute observer of American society in action. "I think the war smelled a little funny to people at the time, and they'd just as soon not think about it," he said.

Russell went about researching the Gulf War meticulously, soaking himself in the plentiful documentary material from this most media-infiltrated of conflicts. The complex torture techniques Three Kings shows were drawn from actual photographs and the testimony of US and British prisoners of war.

There were well-documented troubles on the shoot. The studio shaved US$10 million off the budget Russell had requested, resulting in a schedule truncated by 12 days. The pressure got to the whole crew, with Clooney and his director facing off towards the end of their arduous stint in the desert -- Arizona, as it happens, rather than the Middle East. Clooney remained outspoken in his praise for Russell's talent. "We had about three good screaming matches. Never a fist fight. We had some good arguments. It was a much bigger film than David had ever been involved in, and we were having to trust that. I was in over my head, too.

"David is really brilliant at this. His idea was to resensitize people to violence. He didn't just want to show the effect of the gunshot, he wanted to show it literally."

For his part, Russell remained grateful to Clooney -- a real Hollywood liberal, if ever there was one -- for sticking his neck out for the project.

"The main proposition," said Russell, with finality, "is to have a cinematic experience that grabs you and doesn't let go of you until the end, and constantly surprises you. And then at the end you realize -- jeez, there was this historical-political expose along the way. You want to put people in spin cycle. Because if it doesn't work at that level, then you've made a boring film."

On April 26, The Lancet published a letter from two doctors at Taichung-based China Medical University Hospital (CMUH) warning that “Taiwan’s Health Care System is on the Brink of Collapse.” The authors said that “Years of policy inaction and mismanagement of resources have led to the National Health Insurance system operating under unsustainable conditions.” The pushback was immediate. Errors in the paper were quickly identified and publicized, to discredit the authors (the hospital apologized). CNA reported that CMUH said the letter described Taiwan in 2021 as having 62 nurses per 10,000 people, when the correct number was 78 nurses per 10,000

As we live longer, our risk of cognitive impairment is increasing. How can we delay the onset of symptoms? Do we have to give up every indulgence or can small changes make a difference? We asked neurologists for tips on how to keep our brains healthy for life. TAKE CARE OF YOUR HEALTH “All of the sensible things that apply to bodily health apply to brain health,” says Suzanne O’Sullivan, a consultant in neurology at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery in London, and the author of The Age of Diagnosis. “When you’re 20, you can get away with absolute

May 5 to May 11 What started out as friction between Taiwanese students at Taichung First High School and a Japanese head cook escalated dramatically over the first two weeks of May 1927. It began on April 30 when the cook’s wife knew that lotus starch used in that night’s dinner had rat feces in it, but failed to inform staff until the meal was already prepared. The students believed that her silence was intentional, and filed a complaint. The school’s Japanese administrators sided with the cook’s family, dismissing the students as troublemakers and clamping down on their freedoms — with

As Donald Trump’s executive order in March led to the shuttering of Voice of America (VOA) — the global broadcaster whose roots date back to the fight against Nazi propaganda — he quickly attracted support from figures not used to aligning themselves with any US administration. Trump had ordered the US Agency for Global Media, the federal agency that funds VOA and other groups promoting independent journalism overseas, to be “eliminated to the maximum extent consistent with applicable law.” The decision suddenly halted programming in 49 languages to more than 425 million people. In Moscow, Margarita Simonyan, the hardline editor-in-chief of the