Thom Mayne, who has been called the bad boy and angry young man of Los Angeles architecture, is the winner of this year's Pritzker Architecture Prize, considered the profession's highest honor. Mayne, 61, is the first American to win the prize in 14 years.

"I've been such an outsider my whole life," he said in a telephone interview from his office at Morphosis, his firm in Santa Monica, California. "It's just kind of startling."

Given his reputation as a maverick, Mayne's selection as this year's Pritzker laureate would seem to signal his induction into the establishment. That shift would seem to have begun with his selection for three US government projects now rising under the General Services Administration's program to promote "design excellence" in architecture: a glass federal office building in San Francisco that eliminates corner offices in favor of a democratic space, with city views for 90 percent of the workstations; a federal courthouse in Eugene, Oregon, that elevates the courtrooms above a glass plinth; and a satellite facility, crowned with 16 antennas and partly submerged in the landscape, for the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration outside Washington.

PHOTOS: NY TIMES

But Mayne said he saw the prize as a recognition of his iconoclastic approach -- and as a mandate to keep agitating.

"I see this as a validation for architecture in general," he said, "and for me to push even harder."

To be sure, in its citation the Pritzker jury acknowledged Mayne's countercultural roots, calling him "a product of the turbulent 60s who has carried that rebellious attitude and fervent desire for change into his practice, the fruits of which are only now becoming visible in a group of large-scale projects."

Among those is his recent Caltrans District 7 building, a headquarters of the California Transportation Department in downtown Los Angeles. The hulking 1.2-million-square-foot building has cantilevered upper floors and a mechanized perforated skin that adjusts to the light throughout the day, becoming as transparent as glass at dusk.

Like the name of his firm, Morphosis, with its suggested embrace of constant change, Mayne's signature style has been difficult to pin down over the years.

Yet recurring elements run through many Mayne buildings, like blocky jutting shapes, glass and metal, double skins, shifting degrees of light, curvilinear walls and elevators that skip stops.

In New York Mayne has designed a nine-story art and engineering building for Cooper Union in Manhattan and an Olympic Village in Hunters Point, Queens -- a mixed-use waterfront development that is scheduled to go up whether or not the games come to New York in 2012. Reviewing the Cooper Union design, Nicolai Ouroussoff, the architecture critic for The New York Times, praised Mayne for his social optimism and "enthusiasm for the congestion and dynamism on which cities thrive."

Mayne described his style as idiosyncratic.

"The multiplicity of ideas is what I'm interested in," he said. "The hybrid in our society -- where there is no singular idea of what is beautiful."

The Pritzker jury acknowledged this eclectic quality in its citation. "Mayne's approach toward architecture and his philosophy is not derived from European modernism, Asian influences or even from American precedents of the last century," it says. "He has sought throughout his career to create an original architecture, one that is truly representative of the unique, somewhat rootless culture of Southern California, especially the architecturally rich city of Los Angeles."

Born in Waterbury, Connecticut, Mayne began his career as an urban planner after graduating with an architecture degree from the University of Southern California in 1968. Four years later, with five other architects, he formed a new school, the Southern California Institute of Architecture (SCI-Arc), which aimed to bring to Los Angeles the critical attitude toward the profession that was being practiced at Cooper Union in New York and the Architectural Association in London. The school is still operating, although Mayne now teaches at the University of California, Los Angeles.

Around the time of the founding of SCI-Arc, he founded an architectural firm with two school friends who were also teachers.

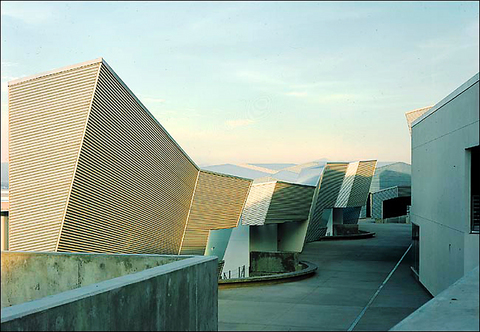

Ouroussoff has described Mayne's early works as "militaristic" and characterized by a "brooding aggression." That style was broken by his 1993 design of Diamond Ranch High School in Pomona, California, one of his first major public commissions, with two rows of fragmented buildings set on either side of a long central sidewalk "canyon" and a monumental stairway embedded in the hillside that doubles as an amphitheater.

His most recent commission, the result of a design competition, is for a new State Capitol building in Juneau, Alaska.

Internationally, Mayne has designed the Hypo Alpe-Adria Center, a mixed-use bank headquarters in Klagenfurt, Austria; the ASE Design Center in Taipei, Taiwan; the Sun Tower in Seoul, South Korea; and a housing project to be completed next year in Madrid.

Mayne is only the eighth American to be honored with a Pritzker since it was first awarded, in 1979 to Philip Johnson. He is to receive a US$100,000 grant and a bronze medallion on May 31 in Chicago's Millennium Park in a ceremony in the Jay Pritzker Pavilion, named for the founder of the prize and designed by the architect Frank Gehry, one of the Pritzker jurors, who won in 1989.

Gehry, who is based in Los Angeles, said he did not think of Mayne as an insurgent so much as an individual. "He's a really authentic architect," he said in a telephone interview. "He's developed his own space and language."

Mayne, too, questioned this persistent characterization of him as contrarian. "I think my clients would tell you I'm a problem solver," he said. "I'm not there to agree with people. I'm there to articulate a point of view."

"Am I insistent and tenacious?" he said. "Absolutely. I could not get this work done if I was not."

At the same time, Mayne added, experience has taught him the necessity -- if not the art -- of compromise. "I've grown up a little bit," he said. "I understand the importance of the negotiation. It is a collective act."

Behind a car repair business on a nondescript Thai street are the cherished pets of a rising TikTok animal influencer: two lions and a 200-kilogram lion-tiger hybrid called “Big George.” Lion ownership is legal in Thailand, and Tharnuwarht Plengkemratch is an enthusiastic advocate, posting updates on his feline companions to nearly three million followers. “They’re playful and affectionate, just like dogs or cats,” he said from inside their cage complex at his home in the northern city of Chiang Mai. Thailand’s captive lion population has exploded in recent years, with nearly 500 registered in zoos, breeding farms, petting cafes and homes. Experts warn the

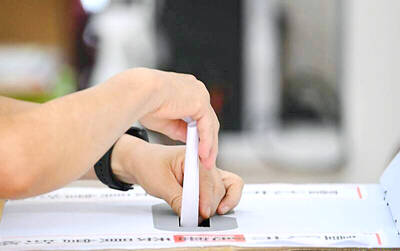

No one saw it coming. Everyone — including the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) — expected at least some of the recall campaigns against 24 of its lawmakers and Hsinchu Mayor Ann Kao (高虹安) to succeed. Underground gamblers reportedly expected between five and eight lawmakers to lose their jobs. All of this analysis made sense, but contained a fatal flaw. The record of the recall campaigns, the collapse of the KMT-led recalls, and polling data all pointed to enthusiastic high turnout in support of the recall campaigns, and that those against the recalls were unenthusiastic and far less likely to vote. That

The unexpected collapse of the recall campaigns is being viewed through many lenses, most of them skewed and self-absorbed. The international media unsurprisingly focuses on what they perceive as the message that Taiwanese voters were sending in the failure of the mass recall, especially to China, the US and to friendly Western nations. This made some sense prior to early last month. One of the main arguments used by recall campaigners for recalling Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) lawmakers was that they were too pro-China, and by extension not to be trusted with defending the nation. Also by extension, that argument could be

Aug. 4 to Aug. 10 When Coca-Cola finally pushed its way into Taiwan’s market in 1968, it allegedly vowed to wipe out its major domestic rival Hey Song within five years. But Hey Song, which began as a manual operation in a family cow shed in 1925, had proven its resilience, surviving numerous setbacks — including the loss of autonomy and nearly all its assets due to the Japanese colonial government’s wartime economic policy. By the 1960s, Hey Song had risen to the top of Taiwan’s beverage industry. This success was driven not only by president Chang Wen-chi’s