A housewife calls to talk about a broken sewer pipe. A student calls to talk about a lost love. A shopkeeper calls to say what he thinks of the violent insurgency that has swept his country.

The callers have reached Iraq's first talk radio station, Radio Dijla, which opened in April and has been putting Iraqis' opinions directly on the air, mainlining democracy from a two-story villa in central Baghdad for 19 hours a day.

PHOTO: NY TIMES

In all, about 15 private radio stations have sprung up since the US occupation began, but Dijla, whose name is Arabic for "Tigris," is the first to serve only talk. The station is one of the most listened-to in Baghdad, according to its employees, a claim that appears to have merit, judging by its broad following among the city's taxi drivers, housewives, students and late-night listeners, who tune in to a night talk show about relationships.

The station receives an average of 185 calls an hour, far more than it can handle, according to its owner, Ahmed al-Rakabi, who said he planned to buy more telephone lines to accommodate callers. Most calls are about the nuts and bolts of life. Many public services have not recovered since the US occupation began more than a year ago. Daily power failures persist. Piles of trash are heaped on city streets. In poorer areas, leaky sewage pipes taint water supplies.

"Iraqi citizens have big problems but nobody listens to them," said Haidar al-Ameen, 34, a businessman, who listens to Dijla while driving. "If I have no gun, there's no one who is going to listen to me. The government has no time to listen."

The station forces the government to make time. Local and federal officials come as guests and are grilled by listeners. The talk shows result in uncomfortable situations, which would have been unheard of in the time of Saddam Hussein, when government officials were royalty and ordinary citizens were mere supplicants who were easily ignored.

On a recent Thursday, callers from the Mansour neighborhood questioned its local government leader, Ali Laaibi, about one of life's basic necessities.

"Why aren't there any garbage trucks?" a woman caller asked in an urgent voice. "It's been so long since anyone came to take out the garbage."

Another woman caller added, "Please, I don't know where to throw the garbage," and said she had even followed someone she had mistakenly thought was a garbage collector. Laaibi squirmed, trying to reassure the callers that he did in fact have a plan. "We've got 13 million garbage bags and we're going to give them out to people," he said.

Beyond easing the frustrations of daily life, the station provides a chance for Iraqis to talk publicly about politics for the first time in decades. Listeners' calls open a window onto the lives of ordinary Iraqis, whose opinions often go unheard in the frantic pace of bombings, kidnappings and armed uprisings.

"After 35 years of people not being able to say what they wanted, we need something that can translate our feelings," said Imad al-Sharaa, a news editor at the station.

One such program was broadcast June 30, on the day before Saddam first appeared in court. The program director and host, Majid Salim, asked listeners what they wanted to see happen to him. The answer was something of a surprise for Salim.

"Most people wanted him executed," Salim said.

Another time, Salim asked listeners what they thought about the violent insurgency that has roiled Iraq.

"We asked them, is it terrorism or is it resistance," Salim said. "A very large proportion -- almost 100 percent -- said terrorism. They did not like it."

In the time of Saddam, Iraqi stations other than the official state station were forbidden. Even so, dedicated listeners like Ameen secretly tuned in to the Voice of America and the British Broadcasting Corp and strained to hear Iraq news reports in Arabic.

Those days are still fresh for Salim, who was a host at a station called Youth Radio run by one of Saddam's sons. Callers were prerecorded, and content was censored. "Now I'm free to say anything I want," Salim said.

The radio's staff is overwhelmingly young, which Salim said was a policy of the station from its inception in April. Women in hejabs, the Islamic head covering, and high heels click around the office. Sound engineers move mice at computers. Photocopied pictures of employees' smiling faces are pinned to a bulletin board near a staircase.

Employees like Sharaa, who is 26, bring a fresh sense of optimism to the station. He also writes for the Institute for War and Peace Reporting in London. He said he had been interested in politics from the age of 12, but was not able to apply any of that knowledge until now.

The station was started with seed money from the Swedish government. Its founder, Ahmed al-Rakabi, the former chief of the US-financed Iraqi Media Network, was born in 1969 in Prague, in what was then Czechoslovakia, after his family was forced to leave Iraq to escape political repression under Saddam.

On the station's first day, Salim simply sat at the microphone and asked listeners what they wanted to talk about. Now, in addition to the government official call-in shows, the station has programs in which lawyers answer questions. It also has a program called Fatwa, led by both Sunni and Shiite clerics, which invites callers to discuss differences in religious practices. A fatwa is an order from a religious leader.

The late-night show in which people call in to dedicate songs and discuss their relationships is particularly popular. The topic is a racy one in Iraq, which has become more conservative since the 1980s, when Saddam, in an effort to appease religious leaders here, required stricter adherence to religious rules.

One night a few weeks ago, a woman called to confess that her boyfriend of four years had just married her closest friend, after she introduced them several weeks before, Salim said. Listeners called to offer sympathy for the unforgivable betrayal.

Ameen welcomes such public heart-to-hearts. "Let everyone talk," he said. "All of Iraqis in different lines must talk, must talk under sun, not in secret."

May 18 to May 24 Pastor Yang Hsu’s (楊煦) congregation was shocked upon seeing the land he chose to build his orphanage. It was surrounded by mountains on three sides, and the only way to access it was to cross a river by foot. The soil was poor due to runoff, and large rocks strewn across the plot prevented much from growing. In addition, there was no running water or electricity. But it was all Yang could afford. He and his Indigenous Atayal wife Lin Feng-ying (林鳳英) had already been caring for 24 orphans in their home, and they were in

President William Lai (賴清德) yesterday delivered an address marking the first anniversary of his presidency. In the speech, Lai affirmed Taiwan’s global role in technology, trade and security. He announced economic and national security initiatives, and emphasized democratic values and cross-party cooperation. The following is the full text of his speech: Yesterday, outside of Beida Elementary School in New Taipei City’s Sanxia District (三峽), there was a major traffic accident that, sadly, claimed several lives and resulted in multiple injuries. The Executive Yuan immediately formed a task force, and last night I personally visited the victims in hospital. Central government agencies and the

Australia’s ABC last week published a piece on the recall campaign. The article emphasized the divisions in Taiwanese society and blamed the recall for worsening them. It quotes a supporter of the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) as saying “I’m 43 years old, born and raised here, and I’ve never seen the country this divided in my entire life.” Apparently, as an adult, she slept through the post-election violence in 2000 and 2004 by the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT), the veiled coup threats by the military when Chen Shui-bian (陳水扁) became president, the 2006 Red Shirt protests against him ginned up by

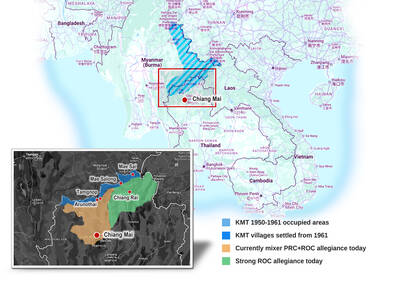

As with most of northern Thailand’s Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) settlements, the village of Arunothai was only given a Thai name once the Thai government began in the 1970s to assert control over the border region and initiate a decades-long process of political integration. The village’s original name, bestowed by its Yunnanese founders when they first settled the valley in the late 1960s, was a Chinese name, Dagudi (大谷地), which literally translates as “a place for threshing rice.” At that time, these village founders did not know how permanent their settlement would be. Most of Arunothai’s first generation were soldiers