With its bold and luminous cut-glass design, the Shanghai Grand Theater can stake a claim to being the heart of this city, and the dazzling impression it makes fits this pulsing business center's glittery self-image to a T.

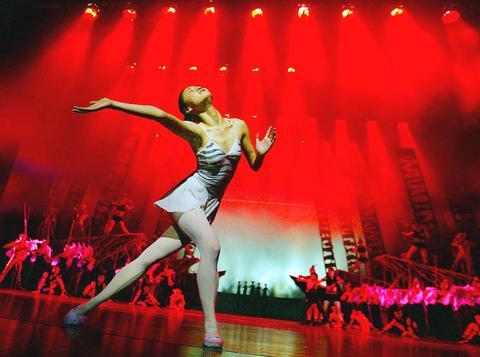

On a recent evening here, as a full house settled in to watch an entirely Chinese production of a Broadway-style dance theater show, Wild Zebra, the opening event in an international dance competition, the city's vice mayor delivered a booming inaugural exhortation that recalled the style of party cadres past.

Shanghai, he announced stiffly, is moving toward the great goal of creating a modern international culture center in Asia. His language was perhaps a bit blunt, but given Shanghai's cultural ambitions, it was difficult to gainsay the message for exaggeration.

PHOTO: NY TIMES

For as long as the Communist Party has ruled China, Shanghai has suffered a deep inferiority complex in relation to the capital, Beijing. The early 20th century was Shanghai's moment in the sun, when it had a global reputation as a flashy and fleshy sin city with top-flight Western architecture and a cabaret culture to match.

But much of what was most vibrant then was derived from abroad, at a time when the country was carved up into imperial concessions, and Shanghai was China's main door to the world. Before that, Shanghai, a mere infant of a city, had hardly registered in the long tableau of Chinese history.

Nowadays the city's cultural profile is changing as fast as its skyline, which barely 15 years ago was a drab and low-slung jumble and today ranks easily as one of the world's most fantastic. Determined to raise the city to the level of regional rivals like Tokyo and Hong Kong as well as Beijing, Shanghai officials have made culture a major priority.

PHOTO: NY TIMES

Beijing has its Forbidden City, its prestigious national schools and museums, its centuries-old neighborhoods that breathe Chinese culture, none of which Shanghai can realistically challenge. But like Tokyo, all but destroyed in World War II, this city is making a virtue of its newness.

As a cornerstone of the revival, which began in earnest in the early 1990s, the Shanghai government spent US$226.8 million, an immense sum in a country still classified as a developing nation, to build a world-class cultural complex in the center city. The recently built structures include the Shanghai Grand Theater, the equally striking Shanghai Museum -- in the shape of an ancient Tang vessel -- and the Shanghai Art Museum.

The city's investment in premium performance and exhibition spaces, though still modest in comparison with major Western artistic centers, has given Shanghai not only a blush of self confidence but also a cockiness in its rivalry with Beijing.

"Shanghai can already attract talent from all over the country, in fact all over the world," said Chen Feihua, director of the Shanghai dance school that created Wild Zebra. "Our production values are broader and fit international tastes. Wild Zebra has toured on the best stages of Europe, Paris, Berlin, Madrid and other cities, and there is a business element to this that is very particular to Shanghai."

Build and hope

Shanghai's strategy of build and hope the visitors come seems to be gathering momentum but draws mixed reviews even among the city's artists, who are debating how the city goes about becoming a world-class cultural center.

An ambitious private museum, the Shanghai Gallery of Art, opened in January at Three on the Bund, a lavishly restored building in the historic riverfront district. It has become a premier place for displaying new Chinese artists and established stars. "Shanghai has already become an attractive cultural city," Weng Ling, director of the museum, said. "What we need now is more professionalism, more cultural exchanges and more support for artists."

Across the Huangpu River in the Pudong district, reclaimed swampland that is now home to the city's tallest, most gaudily lighted skyscrapers, the city government is planning a new art museum in collaboration with the Guggenheim Museum in New York, raising doubts among some who wonder whether Shanghai is going too far, too fast.

Too much too fast?

"A year ago someone told me that China has built 35 cultural complexes, but who is going to perform in them?" asked Kai-Yin Lo, a Hong Kong designer who has advised that city on its artistic development. "The Germans and the Japanese have learned the lesson of hardware: that without the software, you can't maintain the flow. Just look at Bilbao."

"Freedom, too, is very important," she added. "That is what we in Hong Kong can boast."

Urban and cultural development experts agree that museums and other institutions are a starting point. But they say that to emerge as a real cultural powerhouse, a city must fulfill a variety of criteria, including some that defy government planning here.

"Cities that are really vibrant are creative in a lot of different ways," said Richard Florida, a professor of economic development at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh and the author of The Rise of the Creative Class: And How It's Transforming Work, Leisure, Community and Everyday Life. "You look at a city like Pittsburgh, which built huge artistic institutions, really huge places, and drove all of their artists out -- people like Andy Warhol or Billy Strayhorn, because they were too edgy and unconventional, or maybe gay."

Florida said that, so far, the greatest cities of East Asia were falling short of these criteria. "It is important to have the institutions, but you also need vibrant street culture and an open culture, not only openness toward ethnic diversity, but also diversity in sexual orientation and freedom of expression," he said. "Asia certainly needs a city like this, and Shanghai could be the one. Certainly the city that figures it out first will have some tremendous advantages."

By reputation Shanghai is China's most cosmopolitan city, but even some artists who have succeeded here say the city falls short of the diversity needed to become a world-class cultural center.

"They don't have any international students, and I haven't noticed any international teachers, either," said Yuan Yuan Tan, 28, a native of Shanghai who dances with the San Francisco Ballet. "If Shanghai wants to be an international cultural center, they have to do something about that. The reason I left is that I wanted to explore what ballet is all about, and if I had stayed put, that wouldn't have happened."

Standing on its own

By one important measure, however, Shanghai has already succeeded. Increasingly, artists based here have proved they can flourish internationally with little need, as in the past, to go to Beijing first to establish themselves.

"As a new city, the software or the quality of the people and their artistic taste has to be boosted gradually," said Yang Fudong, a specialist in elaborate and deliberately puzzling multimedia displays who has become one of China's best known artists internationally.

At the Shanghai Gallery of Art recently, Yang was putting the finishing touches on a new exhibit, a labyrinthlike construction with two film projectors casting their images across the faces of people who wander inside. "In Shanghai I see people taking in the shows, going to the museums, even taking their children to the museums, and that's a beautiful thing," he said. "One doesn't become a fat man overnight, so we shouldn't be impatient."

As we live longer, our risk of cognitive impairment is increasing. How can we delay the onset of symptoms? Do we have to give up every indulgence or can small changes make a difference? We asked neurologists for tips on how to keep our brains healthy for life. TAKE CARE OF YOUR HEALTH “All of the sensible things that apply to bodily health apply to brain health,” says Suzanne O’Sullivan, a consultant in neurology at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery in London, and the author of The Age of Diagnosis. “When you’re 20, you can get away with absolute

When the South Vietnamese capital of Saigon fell to the North Vietnamese forces 50 years ago this week, it prompted a mass exodus of some 2 million people — hundreds of thousands fleeing perilously on small boats across open water to escape the communist regime. Many ultimately settled in Southern California’s Orange County in an area now known as “Little Saigon,” not far from Marine Corps Base Camp Pendleton, where the first refugees were airlifted upon reaching the US. The diaspora now also has significant populations in Virginia, Texas and Washington state, as well as in countries including France and Australia.

On April 17, Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫) launched a bold campaign to revive and revitalize the KMT base by calling for an impromptu rally at the Taipei prosecutor’s offices to protest recent arrests of KMT recall campaigners over allegations of forgery and fraud involving signatures of dead voters. The protest had no time to apply for permits and was illegal, but that played into the sense of opposition grievance at alleged weaponization of the judiciary by the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) to “annihilate” the opposition parties. Blamed for faltering recall campaigns and faced with a KMT chair

A police station in the historic sailors’ quarter of the Belgian port of Antwerp is surrounded by sex workers’ neon-lit red-light windows. The station in the Villa Tinto complex is a symbol of the push to make sex work safer in Belgium, which boasts some of Europe’s most liberal laws — although there are still widespread abuses and exploitation. Since December, Belgium’s sex workers can access legal protections and labor rights, such as paid leave, like any other profession. They welcome the changes. “I’m not a victim, I chose to work here and I like what I’m doing,” said Kiana, 32, as she