If you go up Zhongshan North Road near the Taipei American School you'll find the old shop for chic dresses gone. In its place is now a bustling restaurant with perhaps the tastiest pizza in town, among other things. It is Scoozi (for the Italian "scuzsi," meaning "excuse me") with its huge sign painted parrot green over the entrance.

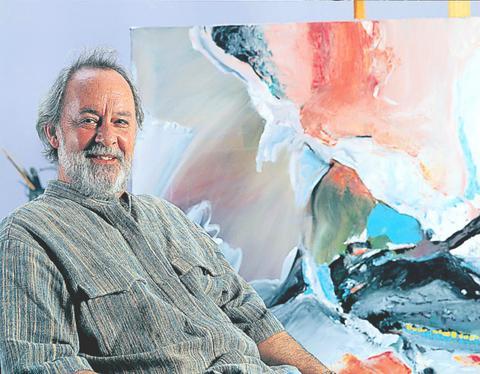

Once acclimatized, you will realize you are not only in a pleasant new culinary world, but in a world of flamboyant art, of spicy, tangy food for the emotions. The restaurant, in fact, doubles as an art gallery, and the one-man show now up on the walls of both floors for the next couple of months and making its unadvertised debut for the artist, is the first-ever public showing of watercolors, acrylics and oil paintings by veteran American landscape architect Robert Egan.

Landscape architects are fond of drawing and creating images from, with and of nature. In the case of Robert Egan, some of the most charming drawings I have seen are his sketches of California dwellings and seasides, filled as they are with his lyrical pencil lines that caress the trees and houses, and dance dappled shadows onto the sunlit ground.

PHOTO COURTESY OF JUSTIN CHOU

In those days, he had already an uncommon eye for lines forever in joyful motion, and managed to incite them no matter what he was rendering. But over the past two decades, the urge has been to break out of the limner's realm, where forms are encased and confined and their boundaries glorified, as in so many sketches of landscapes or landscaped dwelling complexes that enliven the notebooks of architects.

A rumbling began in the early 1990s, when Egan's erstwhile lighthearted sketches began to behave more like paintings, and the watercolors became heavier, turning into acrylics saturated with opacity and a new complexity. The yellows and oranges of the sketch-like paintings now darkened, turning into bluish magentas that seek conflict with teal greens in an onrush of broad and energetic clashing currents. The struggle is between the warm, burning tones of the greens and the fiery ice of the blues, between harmony and conflict, where on many occasions it is the tension in unresolved riddles that reigns triumphant.

But these are part and parcel of a genuine artist's life in art. There is no attempt to pose as something one is not, to present an image that does not come straight from the guts, or to select only a "representative" group that would cohere to reinforce some kind of profound "artist's statement." The paintings in this debut are, in fact, a miniature retrospective, pulling together different types of works from the past 15 years or so that Egan has worked and lived in east Asia, with Taiwan as his base.

PHOTO COURTESY OF JUSTIN CHOU

Innocent exuberance celebrating the enchantment of form of the early 1990s can be seen gradually to give way to a growing inner turbulence that finds expression in ever-broader strokes in ever more abstract movements. In Egan's eye the powerful passion inherent in seething tropical island scenes acquires a compelling undercurrent of deep, ominous foreboding, as if some unconscious loathing or fear would sweep all form and color into some black hole of annihilation.

Egan's most recent works are often entirely nonfigurative and tend to converge in pounding beats, as if imploding from beyond cognition toward a central fatality in tidal waves of grays, magentas, even eerie greens and reds like haunting aurora borealis, growing in vehemence as they converge toward a center of convoluted discord.

In the world of abstract painting, just as in abstract or classical music, there is no identifiable formal imagery to organize time or space with pre-determinates in relative proportion and interrelationships. Artists must search the depths of their souls to recognize their own persona, and at the same time recognize the techniques and devices that best give it life. And Egan, in true form, has been searching for his own style, and stretching his inner ear to recognize his own voice.

PHOTO COURTESY OF JUSTIN CHOU

The voice -- in his particular use of colors -- is increasingly identifiable as Egan and the style remains on the whole ambiguous and fraught with unresolved conflicts of direction and approach.

The first phases of an artist's flight to artistic maturity often reveal such hesitations and conflicts. They are engendered by the ghosts of extraneous concepts, by the tyrannical influence of revered masters, and by the cruel weight of self-imposed demands that are usually based on value judgments extrinsic to the artist's inner flow of creative energies. Then there is also the problem of spatial, planar unrest that results when particular color combinations produce two- and three-dimensional effects unintended in the original dialogue of shades and hues.

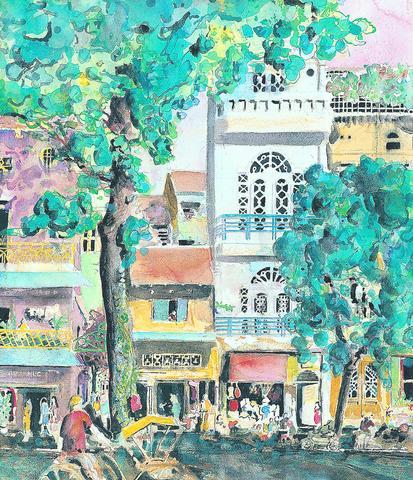

On the overall surface, however, all is bright and rosy, if with the feel of a Mardi Gras samba. The colors alone light up the entire restaurant space with their vibrant energy. The touch is often lively, even fun, with firmly daubed accents of bright, whitened greens and teals laid down in unctuous slabs. The more successful works in terms of overall harmony, balance or resolution are those with veiled figurative references where silhouettes of familiar forms of trees, buildings, waves, ocean rocks, boats, umbrellas, still life and even human figures, manage to impart a zingy virility that effectively pulsates, although seemingly from the colors alone.

PHOTO COURTESY OF JUSTIN CHOU

While the colors give the objects form, it is the brush strokes that give the colors life and spice. Whether painting children staring from behind a barred window in Vietnam, Thai buildings by a khlong, French-style Vietnamese buildings fronted by elegant trees, the sandy rocks of Kenting's coast, or beach palms swaying over crashing waves, Egan always comes across as a seasoned draftsman, an assured hand at the painting easel, and someone with an uncanny eye for the reality of colors in perception. In short, Egan's paintings exude a personal vitality and a highly emotional aura that we do not usually notice in such scenes.

This is because each time Egan returns to do figurative paintings after his self-searching in abstract compositions, he brings to the works the power of colors that most ordinary landscape painters do not explore.

From his nonfigurative works Egan learns about the weight of colors in space, and the power of colors in motion. And once back in a relatively more figurative mode, Egan puts this weight and motion to work.

It is not often that painters wait so long before making their professional debut as artists. Robert Egan, even in this first showing, has proved himself to be a painter of uncommon technical command, as well as of unusual emotional intensity. The tensions and knots are very much part of our particular time and our particular place. But the energy, the heaving inner torment and the dynamic palette, are Egan's alone.

Exhibition note

What: Asia Landscape Passages by Robert Egan

When: Open for the next three months.

Where: Scoozi, 762 Zhongshan N Rd, Sec 6, Taipei (

On April 26, The Lancet published a letter from two doctors at Taichung-based China Medical University Hospital (CMUH) warning that “Taiwan’s Health Care System is on the Brink of Collapse.” The authors said that “Years of policy inaction and mismanagement of resources have led to the National Health Insurance system operating under unsustainable conditions.” The pushback was immediate. Errors in the paper were quickly identified and publicized, to discredit the authors (the hospital apologized). CNA reported that CMUH said the letter described Taiwan in 2021 as having 62 nurses per 10,000 people, when the correct number was 78 nurses per 10,000

As we live longer, our risk of cognitive impairment is increasing. How can we delay the onset of symptoms? Do we have to give up every indulgence or can small changes make a difference? We asked neurologists for tips on how to keep our brains healthy for life. TAKE CARE OF YOUR HEALTH “All of the sensible things that apply to bodily health apply to brain health,” says Suzanne O’Sullivan, a consultant in neurology at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery in London, and the author of The Age of Diagnosis. “When you’re 20, you can get away with absolute

May 5 to May 11 What started out as friction between Taiwanese students at Taichung First High School and a Japanese head cook escalated dramatically over the first two weeks of May 1927. It began on April 30 when the cook’s wife knew that lotus starch used in that night’s dinner had rat feces in it, but failed to inform staff until the meal was already prepared. The students believed that her silence was intentional, and filed a complaint. The school’s Japanese administrators sided with the cook’s family, dismissing the students as troublemakers and clamping down on their freedoms — with

As Donald Trump’s executive order in March led to the shuttering of Voice of America (VOA) — the global broadcaster whose roots date back to the fight against Nazi propaganda — he quickly attracted support from figures not used to aligning themselves with any US administration. Trump had ordered the US Agency for Global Media, the federal agency that funds VOA and other groups promoting independent journalism overseas, to be “eliminated to the maximum extent consistent with applicable law.” The decision suddenly halted programming in 49 languages to more than 425 million people. In Moscow, Margarita Simonyan, the hardline editor-in-chief of the