The 19th century Japanese Gothic novelist Kyoka Izumi's works have been drawing new attention. His play Tenshu Monogatari, or "The Tale of Himeji Castle," has been repeatedly adapted for stage, TV and cinema in Japan in recent years.

Tonight, as part of the CKS Cultural Center's (

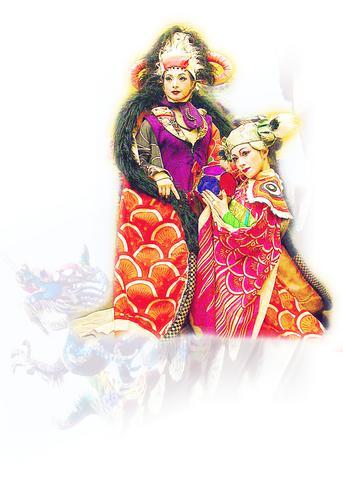

PHOTO: VICO LEE, TAIPEI TIMES

The tragic love story is set in western Japan around the 17th century. Tomihino, a beautiful married princess, commits suicide because of her obsessive love for the lord of Himeji castle. Her spirit possesses the wooden head of a lion, making it cry tears of blood. As a result, people in the feudal realm of Himeji believe that devils live in Tenshu, on the top floor of Himeji castle.

On an autumn evening, Tomi, princess of Himeji castle is having a feast to welcome her sister. The Prince is out hunting and catches a beautiful giant eagle. Tomi steals the eagle to give it to her sister. The Prince's henchmen later find that the eagle is missing. They assume that it has escaped to Tenshu, but no one dares to set foot there to catch it. A young warrior Zusyonosuke, whom the prince blames for losing the eagle, is assigned to search for the eagle in Tenshu. He is told that if he does not come back with the eagle, he must commit suicide.

When the princess meets Zusyonosuke she is immediately moved by his loyalty and asks him to run away from the castle. In love with Tomi at first sight, Zusyonosuke returns in no time to see Tomi again. Tomi returns his love, but other warriors are now in hot pursuit of Zusyonosuke. The two lovers escape to Tenshu and hide behind the possessed lion's head. Failing to find Tomi and Zusyonosuke, their angry pursuers stab at the eyes of the lion head, blinding the two behind it. After the warriors leave, the two lovers realize that they have to die for their secret love.

In adopting the play, Satoshi Miyagi, director of Tenshu Monogatari said he aims to satirize modern Japanese society.

"When Kyoka Izumi wrote the play around 1910, he was using a tale set in the 17th century to satirize post World War I Japan. To remain true to the author's intention, my adaptation also expresses the issue of modern Japan," said Satoshi at the rehearsal of the show.

Satoshi's main adjustment is in his use of bunraku, which has two performers playing the same role. One acts as a voice-over while the other silently acts out the movements of the character in a puppet-like manner. An elegant and delicate actress plays Tomi, but her voice rumbles like an old man. The warrior Zusyonosuke's narrator is a young girl with a sweet voice.

"The status of Japanese women 90 years ago was lower. They were not allowed to do anything. Even if their lovers betrayed them, they were not supposed to complain. I have a male voice speaking for the princess to show that women at the time had strong feelings but lacked a voice for their indignation," Satoshi said.

Satoshi went on to explain how he hopes the audience will perceive the role-reversal in the performance. "If we think that the male voice is powerful and solemn and the female voice tender, it's just that we have been conditioned by the society to see that men are are powerful. With the voice of the sexes reversed, we are free to reconsider the strength of both sexes."

Founded in 1995, Ku Na'uka's performances have been credited with ingeniously blending tradition with the modernity. One example is the accompanying contemporary, or pop music, with Greek tragedies or Shakespearean plays. This quality is also evident in Tenshu Monogatari, in which even the genres of bunraku, kabuki and noh become one seamless new style. For the director, the mixture was, in a way, traditionally Japanese.

"Japanese culture has always been a mixture of different customs and eras. Japan's theater performances were also meant to reflect their times, so we're just trying to reflect that. There's no divide of the traditional and the modern. What is traditional now used to be modern in its time," Satoshi said.

For your information :

Ku Na'uka Theater Company will perform Tenshu Monogatari at 7:30pm tonight and tomorrow, and at

2:30pm on Sunday, at the National Theater. Tickets range from NT$400 to NT$1,500 and are available at the CKS Cultural Center. As of Wednesday, some 70 percent of the tickets had been sold. For more information, call (02) 2343 1647 or go to www.artsticket.com.tw

In the next few months tough decisions will need to be made by the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) and their pan-blue allies in the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). It will reveal just how real their alliance is with actual power at stake. Party founder Ko Wen-je (柯文哲) faced these tough questions, which we explored in part one of this series, “Ko Wen-je, the KMT’s prickly ally,” (Aug. 16, page 12). Ko was open to cooperation, but on his terms. He openly fretted about being “swallowed up” by the KMT, and was keenly aware of the experience of the People’s First Party

Aug. 25 to Aug. 31 Although Mr. Lin (林) had been married to his Japanese wife for a decade, their union was never legally recognized — and even their daughter was officially deemed illegitimate. During the first half of Japanese rule in Taiwan, only marriages between Japanese men and Taiwanese women were valid, unless the Taiwanese husband formally joined a Japanese household. In 1920, Lin took his frustrations directly to the Ministry of Home Affairs: “Since Japan took possession of Taiwan, we have obeyed the government’s directives and committed ourselves to breaking old Qing-era customs. Yet ... our marriages remain unrecognized,

Not long into Mistress Dispeller, a quietly jaw-dropping new documentary from director Elizabeth Lo, the film’s eponymous character lays out her thesis for ridding marriages of troublesome extra lovers. “When someone becomes a mistress,” she says, “it’s because they feel they don’t deserve complete love. She’s the one who needs our help the most.” Wang Zhenxi, a mistress dispeller based in north-central China’s Henan province, is one of a growing number of self-styled professionals who earn a living by intervening in people’s marriages — to “dispel” them of intruders. “I was looking for a love story set in China,” says Lo,

During the Metal Ages, prior to the arrival of the Dutch and Chinese, a great shift took place in indigenous material culture. Glass and agate beads, introduced after 400BC, completely replaced Taiwanese nephrite (jade) as the ornamental materials of choice, anthropologist Liu Jiun-Yu (劉俊昱) of the University of Washington wrote in a 2023 article. He added of the island’s modern indigenous peoples: “They are the descendants of prehistoric Formosans but have no nephrite-using cultures.” Moderns squint at that dynamic era of trade and cultural change through the mutually supporting lenses of later settler-colonialism and imperial power, which treated the indigenous as