A stone plaque next to the Wu Shi Ren Gong Temple (五十人公廟) near Nuannuan (暖暖), Taipei County, bears witness to the history of Taiwan's assam indigo industry, which thrived up until the end of the 19th century. "In the mid-Qing dynasty, a group of ancestors living near the Keelung River grew assam indigo at the present location of this temple, for trade in Mangga (present-day Wanhua)," it says.

One hundred years after chemical dyes replaced the assam indigo dyes, Wang Guo-wei (

PHOTO: VICO LEE, TAIPEI TIMES

All the fabrics were colored using dyestuff from Wang's assam indigo farm, which he tends by himself. He is currently awaiting approval for financial assistance from the Council of Labor Affairs that he hopes will allow him to hire more workers to begin larger-scale production of indigo handicrafts and have them sold in major cities in the country by the end of this year.

A member of Keelung's Culture and History Workshop, Wang started growing assam indigo to prepare for the 2001 Local Culture Exhibition at the Presidential Palace. Although outsiders often associate Keelung with marine industries, the workshop wanted to show a different side of Keelung. "Assam indigo agriculture is the oldest industry in Keelung," Wang said.

When Han Chinese came from Fujian province to the Keelung hills, which were inhabited by the Ketagalan Aboriginal tribe, they introduced assam indigo and sweet potatoes. Eventually their inter-married descendants grew the plant, produced dyestuff from it, and sold indigo dye to Fujian dress-makers.

"The damp climate of Keelung is perfect for the plant. They outshine their mainland-Chinese counterparts in depth and brilliance of the blue," said Wang, who still vaguely remembers seeing his grandparents harvesting the plant on the family farm.

In the late-19th century, two years of drought destroyed many of the indigo farms. At the encouragement of British traders, farmers turned to tea plantation, which is equally suited to Keelung's misty weather. Soon afterward, the Qing dynasty allowed coal mining in Taiwan, and the remaining indigo farmers then abandoned farming for the easier job of mining. Wang's parents were two of the last indigo farmers.

At its peak, assam indigo was Taiwan's top export in terms of income and Nuannuan's main source of revenue.

But Nuannuan residents were never dye craftsmen, because there were too few sunny days to dry the dye-work. Wang turned to the National Taiwan Craft Research Institute and craftsmen in Taipei county's Sanhsia, where a small amount of dyestuff and dye-work continues to be produced, for assistance in dyeing techniques.

Wang began by planting assam indigo on his land and extracting dyestuff from the plants months later. When the Keelung Culture and History Workshop expressed enthusiasm for the resulting indigo fabrics, Wang started recruiting students for his "Dyeing Workshop" (染工坊) in 2002. Classes were held at his garden.

"Indigo dyeing is the industry of our ancestors. I want to try and bring it back to Nuannuan," Wang said.

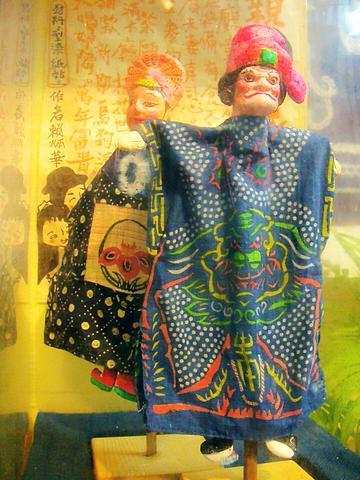

The works on show at the exhibition, mostly by local housewives with previous training in tailoring, quilting or painting, are mostly up to market standards. There are delicate purses and cushions dyed in star patterns using the stitch dyeing method, handkerchiefs dyed in floral designs with stencils, curtains dyed with clamping and pleating techniques and skirts soaked in the indigo vat five times to acquire gradual shades of blue. Many fabrics are even more refined and creative than the imported goods from China and Indonesia available in fashionable Taipei boutiques.

Wang attributed the rising popularity of learning indigo dyeing to the localized school curriculum in recent years. As part of the local culture and history education program, some elementary schools have introduced their pupils to the ancient craft.

Wang is eager to put works by his students on the market, but is taking cautious steps in that direction. "I don't want to have them on the market before the right time, otherwise they would end up in street stalls. If that happens, the students will feel very sad because they have put so much effort into their work," Wang said.

There are other obstacles to conquer, as well, before the fabrics can hit the market. "After residents gave up the plant 100 years ago, it's not easy to persuade them back into the business. I have talked two families into growing assam indigo, and have found farmers need a lot of convincing. I have to prove to them that it's a viable option," Wang said.

Wang's farm produced over 100kg of dyestuff last year, most of which was used by the 25 students in the workshop from December to March. From 1kg of dyestuff, only 40 45cm-by-45cm handkerchiefs can be dyed. Wang said the commercial potential is therefore limited. "The main problem is the source of assam indigo," Wang said.

"I just want to sow the seeds now, and if more people grow to love indigo dyeing, there will be more farmers and more people wanting to buy the works.9ji Then, indigo dyeing will return to Nuannuan."

Cozy East Nursery Garden is located at No. 12 Tong-ding Rd., Nuannuan, Keelung (基隆市暖暖區東碇路12號)

Following the shock complete failure of all the recall votes against Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) lawmakers on July 26, pan-blue supporters and the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) were giddy with victory. A notable exception was KMT Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫), who knew better. At a press conference on July 29, he bowed deeply in gratitude to the voters and said the recalls were “not about which party won or lost, but were a great victory for the Taiwanese voters.” The entire recall process was a disaster for both the KMT and the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP). The only bright spot for

Water management is one of the most powerful forces shaping modern Taiwan’s landscapes and politics. Many of Taiwan’s township and county boundaries are defined by watersheds. The current course of the mighty Jhuoshuei River (濁水溪) was largely established by Japanese embankment building during the 1918-1923 period. Taoyuan is dotted with ponds constructed by settlers from China during the Qing period. Countless local civic actions have been driven by opposition to water projects. Last week something like 2,600mm of rain fell on southern Taiwan in seven days, peaking at over 2,800mm in Duona (多納) in Kaohsiung’s Maolin District (茂林), according to

Aug. 11 to Aug. 17 Those who never heard of architect Hsiu Tse-lan (修澤蘭) must have seen her work — on the reverse of the NT$100 bill is the Yangmingshan Zhongshan Hall (陽明山中山樓). Then-president Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石) reportedly hand-picked her for the job and gave her just 13 months to complete it in time for the centennial of Republic of China founder Sun Yat-sen’s birth on Nov. 12, 1966. Another landmark project is Garden City (花園新城) in New Taipei City’s Sindian District (新店) — Taiwan’s first mountainside planned community, which Hsiu initiated in 1968. She was involved in every stage, from selecting

As last month dawned, the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) was in a good position. The recall campaigns had strong momentum, polling showed many Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) lawmakers at risk of recall and even the KMT was bracing for losing seats while facing a tsunami of voter fraud investigations. Polling pointed to some of the recalls being a lock for victory. Though in most districts the majority was against recalling their lawmaker, among voters “definitely” planning to vote, there were double-digit margins in favor of recall in at least five districts, with three districts near or above 20 percent in