In about two-thirds of the way through Something's Gotta Give, Diane Keaton bursts into tears. Her character, a divorced, middle-aged playwright named Erica Barry, has seen her quiet life of professional fulfillment and romantic disappointment unexpectedly disrupted by love and then, in short order, by heartbreak. Erica's sobs, sniffles and wails seem endless and uncontrollable, expressing every conceivable combination of hurt, humiliation and anger. Her crying jag, which seems to last for several months, continues without interruption through a half-dozen cuts and scene changes, carrying Erica through nearly every room in her large, airy East Hampton beach house.

But Something's Gotta Give, which opens in Taiwan today, is a comedy. At the sneak preview I attended, the harder Erica cried, the harder the audience laughed, which I might have found disturbing if I had not been laughing so helplessly myself.

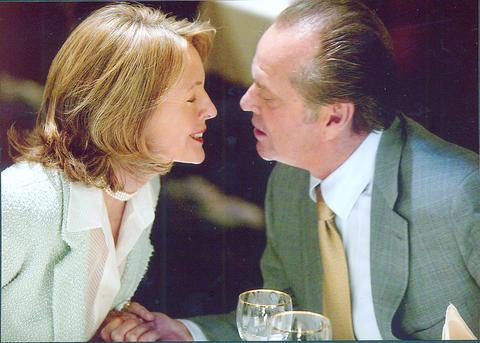

PHOTO COURTESY OF WARNER MOVIES

This mirth was not cruel or derisive; it was instead an odd but nonetheless apt measure of the audience's sympathy and affection for Erica and a tribute to Keaton's unparalleled comic skill. Nobody else working in movies today can make her own misery such a source of delight or make the spectacle of utter embarrassment look like a higher form of dignity. Erica is by turns prickly, indecisive, uptight, vulnerable, self-assured and skittish: traits Keaton blends into a performance that is at once entirely coherent and dizzyingly unpredictable.

The smash hit play Erica eventually writes -- her delicious revenge on the man who caused her such pain -- is called A Woman to Love, which would have been a much better title for this unusually satisfying comic romance than the empty and generic one it has. Erica lifts the phrase from one of her two suitors, a smooth-faced, star-struck young doctor named Julian, played in tongue-in-cheek Ralph Bellamy deadpan by Keanu Reeves. The movie is built around the wonderful and entirely persuasive conceit that both Reeves and Jack Nicholson could find themselves hopelessly smitten with an intelligent and accomplished woman in her 50's.

Nicholson plays Harry Sanborn, a rich, 62-year-old bachelor who has devoted his life to philosophy: the Playboy Philosophy, circa 1966. Harry prides himself on never having dated a woman over 30, and at the start of the movie his babe of the moment is Erica's daughter, Marin (Amanda Peet).

Nicholson may not, strictly speaking, be playing himself, but he seems to have prepared for the role by studying a few decades' worth of interviews and magazine profiles celebrating his unapologetic libertinism. And if his casting is an obvious joke, it is nonetheless a good one, thanks to his devilish combination of high-spi-rited rakishness and old-school gallantry.

After suffering a heart attack during a bit of hanky panky with Marin, Harry finds himself under Erica's reluctant care, stranded in her house, where the rules of bedroom farce are strictly enforced. Logy and disoriented, Harry

stumbles into Erica's bedroom and sees her naked, an event that casts an awkward pall over their relationship as well as foreshadowing its eventual consummation.

Something's Gotta Give was written and directed by Nancy Meyers, who has, from Private Benjamin to What Women Want, demonstrated a thorough, if not always breathtakingly original, flair for the conventions of mainstream quasi-feminist comedy. She and Keaton have worked together before, in the yuppie crisis comedy Baby Boom and the retrofitted Father of the Bride pictures, in which Keaton was unimaginatively relegated to the role of Steve Martin's patient wife and obliging straight man.

Something's Gotta Give, true to form, does not really depart from the genial, sentimental formulas of its genre. Some of the jokes are flat, and some scenes that should sparkle with screwball effervescence sputter instead. But what Meyers lacks in inventiveness she makes up for in generosity, to the actors and therefore to the

audience.

Nicholson and Keaton -- last seen together, in rather different circumstances, as Eugene O'Neill and Louise Bryant in Warren Beatty's Reds -- spar with the freedom of professionals with nothing left to prove, and Nicholson has the gentlemanly grace to step aside and let Keaton claim the movie. She in turn brings out the best in everyone around her. Reeves, liberated from the Matrix and the burden of being the One, mocks his own mellow blandness but conveys his character's ardor for Erica without the slightest hint of facetiousness.

Frances McDormand, as Erica's sister, a professor of women's studies, sidesteps the temptations of caricature and tosses off some of the movie's funniest lines. Peet, zany and appealing in an underwritten role, continues her steady, zigzagging growth into one of the most interesting (and, by this critic at least, often underestimated) young actresses around. If she keeps it up, she could be the next Diane Keaton.

Which, as of this writing, is about the highest praise I can confer. After Erica's tears have dried, she and the audience are rewarded with a giddy, Lubitschean third act, which swirls through Manhattan and the Caribbean before touching down -- but of course -- in Paris for a sweetly predictable denouement. If Erica's distress makes you laugh, her richly deserved joy might just bring a tear to your eye.

Julian had it right: she is a woman to love. "You're incredibly sexy," he says to her at one point.

"I swear to God, I'm not," she replies.

I swear to God, she's wrong.

The canonical shot of an East Asian city is a night skyline studded with towering apartment and office buildings, bright with neon and plastic signage, a landscape of energy and modernity. Another classic image is the same city seen from above, in which identical apartment towers march across the city, spilling out over nearby geography, like stylized soldiers colonizing new territory in a board game. Densely populated dynamic conurbations of money, technological innovation and convenience, it is hard to see the cities of East Asia as what they truly are: necropolises. Why is this? The East Asian development model, with

June 16 to June 22 The following flyer appeared on the streets of Hsinchu on June 12, 1895: “Taipei has already fallen to the Japanese barbarians, who have brought great misery to our land and people. We heard that the Japanese occupiers will tax our gardens, our houses, our bodies, and even our chickens, dogs, cows and pigs. They wear their hair wild, carve their teeth, tattoo their foreheads, wear strange clothes and speak a strange language. How can we be ruled by such people?” Posted by civilian militia leader Wu Tang-hsing (吳湯興), it was a call to arms to retake

This is a deeply unsettling period in Taiwan. Uncertainties are everywhere while everyone waits for a small army of other shoes to drop on nearly every front. During challenging times, interesting political changes can happen, yet all three major political parties are beset with scandals, strife and self-inflicted wounds. As the ruling party, the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) is held accountable for not only the challenges to the party, but also the nation. Taiwan is geopolitically and economically under threat. Domestically, the administration is under siege by the opposition-controlled legislature and growing discontent with what opponents characterize as arrogant, autocratic

When Lisa, 20, laces into her ultra-high heels for her shift at a strip club in Ukraine’s Kharkiv, she knows that aside from dancing, she will have to comfort traumatized soldiers. Since Russia’s 2022 invasion, exhausted troops are the main clientele of the Flash Dancers club in the center of the northeastern city, just 20 kilometers from Russian forces. For some customers, it provides an “escape” from the war, said Valerya Zavatska — a 25-year-old law graduate who runs the club with her mother, an ex-dancer. But many are not there just for the show. They “want to talk about what hurts,” she