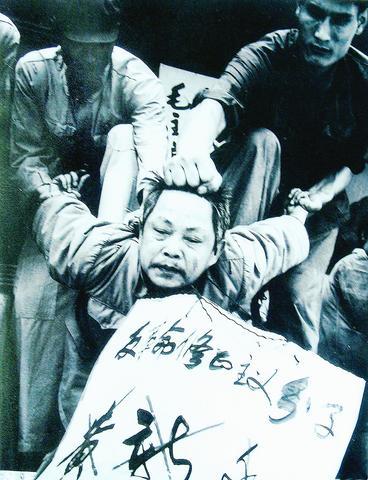

Even after two and a half decades of reform and opening to the outside world, Chinese rulers are not ready to discuss the chaos of the Cultural Revolution (1966 to 1976), when tens of millions of families suffered tragedies.

"Still in China there is very little chance of a thorough examination of that period," says Carma Hinton, who was studying in a Chinese school when Mao Zedong (

"Mao had a very delusional idea about his prestige ... in the way he would be able to control the situation," she said at the Foreign Correspondents Club of Hong Kong after a screening of Morning Sun, a film on those tumultuous times.

PHOTO: AFP

"Things went out of control, he couldn't follow the plans that he had envisioned and he had to call the army to clear up the situation."

Mao, whose 110th birthday was marked last month, died in 1976 and two years later Deng Xiaoping (鄧小平) usurped all power and ushered in reforms that have given China enviable rates of economic growth.

But politically, China is unready to open up, said Hinton.

"The South African model of coming out with the truth and forgiving would be a healthy process for China but for many cultural as well as political reasons, China is not ready for that," she said.

"Exposure to the atrocities of the Cultural Revolution perhaps in some ways will lead to revenge and another cycle of atrocities. Within the Cultural Revolution itself, the victims and victimizers weren't clear-cut. There's a cycle of victim turned victimizer, victimizer turned victim.

"That cycle has already spun several times even within the Cultural Revolution period. So it's a very difficult historical burden and to this day there is no fair, sincere debate," said Hinton, whose film was co-directed with her husband Richard Gordon and Australian academic Geremie Barme.

Her remarks were echoed by Wu Guoguang of the Chinese University of Hong Kong, who said China's current leadership under President Hu Jintao (

"So far I don't see any relaxation from the Hu leadership from the repression over free and critical discussions of Mao and the CR [Cultural Revolution]," Wu said.

"Rather, we saw that the new leadership made great efforts to praise Mao and to justify their status as Mao's successors," said Wu.

"This utilization of Mao in today's Chinese politics may help the new leaders to consolidate their

positions in a power struggle, but it is dangerous in terms of managing state-society relations.

"If the leadership continues to refuse political reform but only turns to Mao to find a way of governance, one day they will find that Mao is actually used by ordinary people to legitimize revolution and rebellion from the bottom up," said Wu.

Hinton too warned of the danger of popular revolt in China.

"We point out in the film that if a system doesn't allow legitimate protest and has no channel for the underclass to participate in the prosperity and participate in the political process, Mao's calls for the right to rebel becomes a real possibility for those types of people," Hinton said.

"Right now, with huge economic gaps and many workers losing their jobs and so on, some people think that during the Cultural Revolution at least, `I could voice my criticism,'" she said.

That remark brought her views as close as possible to those of her father William Hinton, author of Fanshen and other tomes extolling Mao's vision of proletarian revolution, who thinks the current leaders have turned their backs on socialism.

Her father was far from happy with her previous film, The Gate of Heavenly Peace, which examined the crushing of the 1989 student-led pro-democracy movement centered on Tiananmen square. He thought the students, who were opposing a regime he saw as no longer faithful to Mao, were unfairly depicted.

But despite her father's loyalty to Mao, Carma Hinton still found it hard to access precious documents for Morning Sun.

Although many of the people featured in the film still live in China, they were interviewed in the US, because it is "very difficult to do any filming in China," she said, adding that black and white archival footage used in the documentary was collected over a 20-year period.

"Some people [working for state-run media] made copies for themselves and it eventually came out [of China]," Hinton said.

"I wouldn't even bother to ask the Chinese authorities for permission to film because I know it it's a no," she said.

"You can't go to the front door and say we'd like to look at the archives of this period and buy footage ... But one day [when] China is completely open enough to reveal its entire archives, other filmmakers will be able to find other materials to put together other aspects of the story and I can't wait till that day."

For now, whatever material Hinton and her team can find, will make it to a Web site on the subject, www.morningsun.org.

The unexpected collapse of the recall campaigns is being viewed through many lenses, most of them skewed and self-absorbed. The international media unsurprisingly focuses on what they perceive as the message that Taiwanese voters were sending in the failure of the mass recall, especially to China, the US and to friendly Western nations. This made some sense prior to early last month. One of the main arguments used by recall campaigners for recalling Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) lawmakers was that they were too pro-China, and by extension not to be trusted with defending the nation. Also by extension, that argument could be

Aug. 4 to Aug. 10 When Coca-Cola finally pushed its way into Taiwan’s market in 1968, it allegedly vowed to wipe out its major domestic rival Hey Song within five years. But Hey Song, which began as a manual operation in a family cow shed in 1925, had proven its resilience, surviving numerous setbacks — including the loss of autonomy and nearly all its assets due to the Japanese colonial government’s wartime economic policy. By the 1960s, Hey Song had risen to the top of Taiwan’s beverage industry. This success was driven not only by president Chang Wen-chi’s

Last week, on the heels of the recall election that turned out so badly for Taiwan, came the news that US President Donald Trump had blocked the transit of President William Lai (賴清德) through the US on his way to Latin America. A few days later the international media reported that in June a scheduled visit by Minister of National Defense Wellington Koo (顧立雄) for high level meetings was canceled by the US after China’s President Xi Jinping (習近平) asked Trump to curb US engagement with Taiwan during a June phone call. The cancellation of Lai’s transit was a gaudy

The centuries-old fiery Chinese spirit baijiu (白酒), long associated with business dinners, is being reshaped to appeal to younger generations as its makers adapt to changing times. Mostly distilled from sorghum, the clear but pungent liquor contains as much as 60 percent alcohol. It’s the usual choice for toasts of gan bei (乾杯), the Chinese expression for bottoms up, and raucous drinking games. “If you like to drink spirits and you’ve never had baijiu, it’s kind of like eating noodles but you’ve never had spaghetti,” said Jim Boyce, a Canadian writer and wine expert who founded World Baijiu Day a decade