In Swimming Pool Charlotte Rampling first appears in a belted tan raincoat, her hair cut short and her features a mask of no-nonsense Britishness. Her character, Sarah Morton, is a mystery novelist, whose Inspector Durwell books have a loyal, though aging readership. When Sarah encounters a young hotshot writer at her publisher's offices, he is sure to tell her how much his mother loves Inspector Durwell. This is meant as a compliment, but it only piques Sarah's frustration. To help her out of her midlife, midcareer rut, her oleaginous editor (Charles Dance) lends her his house in the Luberon region of southern France, a place swathed in greenery and bathed in soft sunshine.

The contrast with London could not be more obvious, and it is one of several that Francis Ozon, who wrote (with Emanulle Bernheim) and directed this clever, teasing entertainment, lays out with devious nonchalance. Shortly after her arrival at the house, Sarah is joined by the editor's daughter, Julie, whom she believes to be the issue of an unhappy dalliance he had with a local woman many years before.

PHOTO COUIRTESY OF FIDELITE

By parentage Julie may be half English (and Ludivine Sagnier speaks the language well enough), but, at least at first, she is pointedly Sarah's opposite and perhaps the embodiment of certain English prejudices about the rude, undisciplined French -- just as Sarah herself may personify certain cliches about the English. While the older woman values peace and privacy, Julie is loud and wanton. She plays music late into the night, walks around with nothing on and brings home a succession of men for noisy, drunken sex.

The disparity may seem a little overdrawn -- (Murder She Wrote meets Girls Gone Wild) -- but as the story takes shape, Ozon, Rampling and Sagnier complicate it in subtle and fascinating ways. Sarah's veneer of repression and prim disapproval softens in the Mediterranean light and you begin to suspect that what had seemed like reserve was really an

especially refined and graceful expression of sensuality. You can see this in the way Rampling smokes a cigarette, attacks a profiterole in a quiet outdoor cafe, or eyes the waiter, a rustic hunk named Franck (Jean-Marie Lamour), who seems destined to become one of Julie's easy conquests.

The relationship between the women thaws, as Sarah discovers the hurt, abandoned child underneath the late-adolescent bravado. Whereas Rampling is an actress of infinite nuance -- as shown in her wrenching, ravishing performance in Ozon's Under the Sand two years ago -- Sagnier's appeal lies in her directness. She wields her sexual magnetism casually and with the merest dash of self-conscious cruelty.

The two women, the handsome waiter, the hours of idleness, the swimming pool: it sounds like, and on one level is, a scenario worthy of Eric Rohmer.

But Ozon is as perverse as he is resourceful, so he slyly turns his delicate study in generational and cross-cultural sexual rivalry into a suspense thriller. There is a mystery lurking in Julie's past, a dead body in the pool house, a wizened dwarf all dressed in black: omens, premonitions, suspicions that things are not what they seem.

And they aren't, which is as much as I'm inclined to say. Ozon's gift, extended in different directions from movie to movie, is to combine low-key observational intelligence with high literary cunning. In movies like Water Drops on Burning Rocks and 8 Women (both of which featured Sagnier) he likes to wander around confined spaces and to indulge a taste for campy theatricality. And though the camp here is performed in natural light and everyday clothes, it is nonetheless tangible in the way the film plays with

formulas well known to the elderly devotees of Inspector Durwell.

There are comic elements -- like Franck's disco-stud dance moves and the house's caretaker, an obliging rustic named Marcel (Marc Fayolle) -- that are made even funnier by being played in life-and-death earnest. The characters in cheap mystery novels, after all, don't realize what they are: they think they are loyal servants, misunderstood young girls, innocent cafe waiters and plucky, curious English mystery writers. This time, though, the joke is on us.

Swimming Pool, Ozon's first English-language film (with a bit of French thrown in for local color), is simultaneously a thoroughly mannered, mischievously artificial confection and an acute piece of psychological realism. Whose psychology, and which reality, remains ambiguous even after the tart, delicious final twist. After that, the story itself seems to evaporate like the mist over the pool's luminous blue surface. The movie is alluringly insubstantial, like the light and air of the Luberon. You can't hold onto it, but it lingers in your senses and plays tricks with your memory.

May 26 to June 1 When the Qing Dynasty first took control over many parts of Taiwan in 1684, it roughly continued the Kingdom of Tungning’s administrative borders (see below), setting up one prefecture and three counties. The actual area of control covered today’s Chiayi, Tainan and Kaohsiung. The administrative center was in Taiwan Prefecture, in today’s Tainan. But as Han settlement expanded and due to rebellions and other international incidents, the administrative units became more complex. By the time Taiwan became a province of the Qing in 1887, there were three prefectures, eleven counties, three subprefectures and one directly-administered prefecture, with

President William Lai (賴清德) yesterday delivered an address marking the first anniversary of his presidency. In the speech, Lai affirmed Taiwan’s global role in technology, trade and security. He announced economic and national security initiatives, and emphasized democratic values and cross-party cooperation. The following is the full text of his speech: Yesterday, outside of Beida Elementary School in New Taipei City’s Sanxia District (三峽), there was a major traffic accident that, sadly, claimed several lives and resulted in multiple injuries. The Executive Yuan immediately formed a task force, and last night I personally visited the victims in hospital. Central government agencies and the

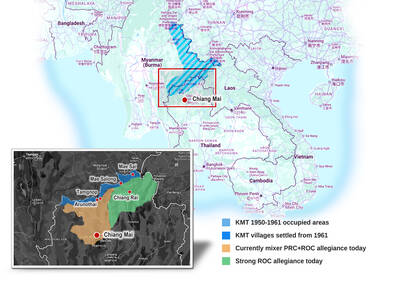

Among Thailand’s Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) villages, a certain rivalry exists between Arunothai, the largest of these villages, and Mae Salong, which is currently the most prosperous. Historically, the rivalry stems from a split in KMT military factions in the early 1960s, which divided command and opium territories after Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石) cut off open support in 1961 due to international pressure (see part two, “The KMT opium lords of the Golden Triangle,” on May 20). But today this rivalry manifests as a different kind of split, with Arunothai leading a pro-China faction and Mae Salong staunchly aligned to Taiwan.

As with most of northern Thailand’s Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) settlements, the village of Arunothai was only given a Thai name once the Thai government began in the 1970s to assert control over the border region and initiate a decades-long process of political integration. The village’s original name, bestowed by its Yunnanese founders when they first settled the valley in the late 1960s, was a Chinese name, Dagudi (大谷地), which literally translates as “a place for threshing rice.” At that time, these village founders did not know how permanent their settlement would be. Most of Arunothai’s first generation were soldiers