In January 2000 I was sitting in the fourth row of Taipei's National Concert Hall listening to Vladimir Ashkenazy conduct the Philharmonia Orchestra in a rehearsal of Brahms's frequently boisterous First Symphony. Watching the famous man, I whispered to myself under my breath, "He's acting out every note!" To my utter amazement, Ashkenazy turned round and looked at me. His acute musician's hearing had detected my presence, and possibly even heard every word.

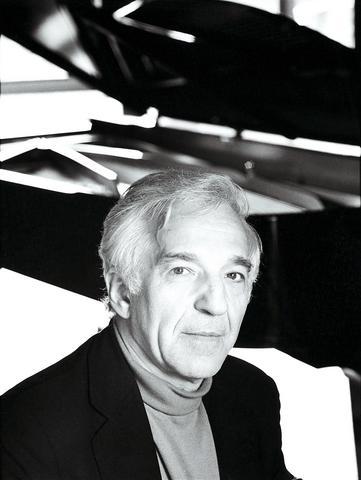

Ashkenazy and the Philharmonia's return visit to Taipei this coming Monday and Tuesday is a major musical event by any standard. London's Philharmonia is the world's most recorded orchestra, and Ashkenazy himself is a giant both as pianist and conductor. This is despite his relatively diminutive stature -- legend has it that he has always avoided playing Liszt because his hands were simply not big enough.

He conducts more than he plays these days -- he conducted over 100 concerts last year, for example. Nevertheless, his recording of Shostakovich's Preludes and Fugues for solo piano won a Grammy for Best Instrumental Soloist in 1999, this despite his saying he has the beginnings of arthritis in the middle finger of his right hand.

PHOTOS COURTESY OF THE NATIONAL CONCERT HALL

Ashkenazy defected from his native Russia in 1963 at the age of 26. By then he had already married his Icelandic-born wife, Thorunn, a music student in the USSR, and found the extra suspicion that having a Western spouse aroused only added to the pressure from the ever-paranoid Soviet authorities.

He took Icelandic citizenship in 1972, but the couple now have their main home in Switzerland. Thorunn Ashkenazy, and their two sons Vovka and Dimitri, are all also recorded classical musicians in their own right.

Pride of place in Monday's concert goes to Mahler's Fifth Symphony, with its famous Adagietto, used to such great effect in Visconti's 1970 film Death in Venice. To hear this long symphony -- it lasts an hour and a quarter -- played live by the Philharmonia will be an experience indeed.

Before the symphony will be Elgar's Enigma Variations, a nostalgic work very popular in the UK but rather less well-known elsewhere. Ashkenazy, however, spends much of his year in London, and has expressed his affection for the English musical scene. When asked, for instance, to comment on Simon Rattle's move from the UK to Berlin last year, he replied that he thought that, contrary to popular belief, there was more genuine enthusiasm for the classics in England than there was in Germany, despite the latter's lavishly-subsidized orchestras and opera houses.

Tuesday's concert will open with Mozart's Piano Concerto No:17 in G, K.453, with Ashkenazy at the keyboard. He has recorded extensively among Mozart's mature piano concertos, some 16 works, but this is clearly a personal favorite as it's the same one he played when he was in Taipei in 2000.

It's particularly interesting that Ashkenazy will be conducting Shostakovich's 10th Symphony, the other item in Tuesday's concert, on this visit. This has been the most discussed of all the composer's 15 symphonies. Some of them have been judged simply as examples of a musical poster art, but rarely the monumental and titanic 10th.

It was premiered in December 1953, following Stalin's death the previous March, and was immediately the subject of an impassioned ideological debate. What was it about? Was it the work of a composer isolated from political events? Or was it, as had been expected, a tribute to the late, great leader?

For most of his life Shostakovich was paraded by the Russian communists as the premier musical spokesman for their socialist system. But Ashkenazy is in no doubt about the composer's real attitude to Stalin. "I was always sure Shostakovich hated the Soviet system, because we all hated it," he once told a UK reporter.

In his youth Ashkenazy was himself persecuted by Stalin's regime, dragged in off the Leningrad streets and roughly told to inform on his fellow students. So it will be fascinating to hear his interpretation of this particular work, dating as it does from a time when he was still living in the USSR.

In the book Testimony, published four years after Shostakovich's death, and offered to the public as his secret credo, the composer speaks frankly about his dissident, anti-Stalin, beliefs. "It's about Stalin and the Stalin years," is what he unambiguously writes about the 10th Symphony.

Whether or not Testimony was really written by Shostakovich, he certainly published what looks very like a mock confession about the 10th. The third movement was "a bit long," he wrote, "though here and there it is a bit short. It would be very valuable to have comrades' opinion on this." Clearly this was intended as a joke, so ridiculous that everyone would see through it, though hopefully not the senior Party officials.

Most probably the 10th Symphony is, as Ian MacDonald -- the Beatles and Shostakovich expert who so tragically took his own life last month -- wrote, "a musical monument to the 50 million victims of Stalin's madness and the supreme thing of its kind composed in the last half century." (The New Shostakovich, 1990)

MacDonald was a friend of mine and he told me on one occasion that the probable reason Shostakovich wasn't shot in the mass purges of the 1930s, when many famous Russian artists perished, was his value to the regime as an internationally famous name, and his supposed status as a major representative of socialist art.

Ashkenazy has spoken about his admiration for MacDonald's book, and endorsed its view of Shostakovich as a lifelong secret dissident.

Taipei is lucky to be seeing both Ashkenazy and the Philharmonia. Both have very busy work schedules. In addition to his position as Conductor Laureate of the Philharmonia, Ashkenazy is also chief conductor of the Czech Philharmonic, musical director of the European Youth Orchestra, and will take up the post of Musical Director of Tokyo's NKH Orchestra for next year's season (he is already their musical adviser).

As well as all this, plus his recordings, he also undertakes one-off projects such as his arrangement of the score for Michael Cacoyannis's film of Chekhov's The Cherry Orchard, starring Charlotte Rampling, in 1999. As one of his friends put it, when Ashkenazy has five minutes free, he puts in ten minutes' work.

June 2 to June 8 Taiwan’s woodcutters believe that if they see even one speck of red in their cooked rice, no matter how small, an accident is going to happen. Peng Chin-tian (彭錦田) swears that this has proven to be true at every stop during his decades-long career in the logging industry. Along with mining, timber harvesting was once considered the most dangerous profession in Taiwan. Not only were mishaps common during all stages of processing, it was difficult to transport the injured to get medical treatment. Many died during the arduous journey. Peng recounts some of his accidents in

“Why does Taiwan identity decline?”a group of researchers lead by University of Nevada political scientist Austin Wang (王宏恩) asked in a recent paper. After all, it is not difficult to explain the rise in Taiwanese identity after the early 1990s. But no model predicted its decline during the 2016-2018 period, they say. After testing various alternative explanations, Wang et al argue that the fall-off in Taiwanese identity during that period is related to voter hedging based on the performance of the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP). Since the DPP is perceived as the guardian of Taiwan identity, when it performs well,

The Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) on May 18 held a rally in Taichung to mark the anniversary of President William Lai’s (賴清德) inauguration on May 20. The title of the rally could be loosely translated to “May 18 recall fraudulent goods” (518退貨ㄌㄨㄚˋ!). Unlike in English, where the terms are the same, “recall” (退貨) in this context refers to product recalls due to damaged, defective or fraudulent merchandise, not the political recalls (罷免) currently dominating the headlines. I attended the rally to determine if the impression was correct that the TPP under party Chairman Huang Kuo-Chang (黃國昌) had little of a

At Computex 2025, Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang (黃仁勳) urged the government to subsidize AI. “All schools in Taiwan must integrate AI into their curricula,” he declared. A few months earlier, he said, “If I were a student today, I’d immediately start using tools like ChatGPT, Gemini Pro and Grok to learn, write and accelerate my thinking.” Huang sees the AI-bullet train leaving the station. And as one of its drivers, he’s worried about youth not getting on board — bad for their careers, and bad for his workforce. As a semiconductor supply-chain powerhouse and AI hub wannabe, Taiwan is seeing