With Who Wants to Be a Millionaire, the writer Steven Knight conjured up a TV show with a rugged punch of a title. It encouraged the worst in contestants, daring them to keep their wits about them while competing in a Dutch-oven environment for the possibility of walking home with up to seven figures in newly disposable income.

By contrast, Knight's script for Dirty Pretty Things, a swift, tangy drama with an equally terse title, pits London's illegal immigrants against the alluring hope of propriety. There's no lifeline that's a phone call away, either. The immigrants are expendable manpower in the war to man the mops, kitchens and bottom-drawer duties of the world of luxury hotels, where they are unnoticed by the public and underpaid and overworked by their employers.

This understated and sure film is set in a world of survivors, a forgotten group of people struggling to bring in enough income so that they don't become disposable. One of them -- the Nigerian Okwe (Chiwetel Ejiofor), who drives a cab and also works as a hotel porter under the large thumb of a smooth-operating night manager named Sneaky (Sergi Lopez) -- seems to be as haunted as he is obsessed.

Portraying Okwe's plight could help to absolve Knight of the flame-out success of Millionaire, which placed a planet-sized karmic debt on the writer's shoulders for sparking the reality show glut. This movie is just the opportunity for Knight to square that account. It is an urban horror story rendered with grim intelligence by the man with the right tools for the job: the British director Stephen Frears.

Okwe, red-eyed and cruising on minimal energy because he works double shifts, is a doctor on the run from his homeland. The movie doesn't elaborate on the troubles that have sent him so far from home; all we really know is that he has left a wife and a daughter behind, and part of his pain comes from pining for them.

That lingering misery is what keeps him safely on the couch of his Turkish roommate, the virginal Senay (Audrey Tautou), refusing to act on the magnetism that keeps her gazing at him adoringly. He's capable of loyalty to the rest of his ad hoc family: Guo Yi (Benedict Wong), a mortuary attendant, and Juliette (Sophie Okonedo), the dangerously close-to-cliche, lovable hooker. The actress's clever portrayal brings shading and warmth to an otherwise stereotyped part.

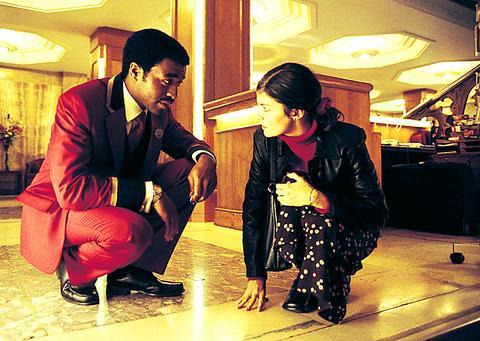

PHOTO COURTESY OF PANDASIA

Dirty Pretty Things suggests a demented sequel to Paul Mazursky's Moscow on the Hudson, a dog-eared fairy tale in which industry and hard work could deliver refugees from evil, or at least into the middle classes. In Dirty Pretty Things, diligence is not its own reward. The decent have to fight the treacherous undertow of their employers, as well as opportunistic and predatory immigration agents.

The tactful, adroit Frears, whose credits include The Grifters, High Fidelity and Dangerous Liaisons, doesn't overemphasize the acrid, fetid atmosphere of hard-working immigrants clambering from one job to the next to stay alive. The spartan, bleary-eyed plainness of the urban landscape of immigrant London makes the film all the more arresting. Frears's low-key curiosity toward what drives outsiders is a crucial element that lubricates the tough, noir melodramatics of the narrative engine. (It's good to see Frears reunited with the immensely gifted cinematographer Chris Menges, who adds a funereal grace to the film.)

As businesslike as the immigrants who work several jobs to stay afloat, Dirty Pretty Things grows grimier and more compelling as it builds a head of steam. The movie gets into gear when Okwe, summoned to clean up a blood-drenched hotel suite, fishes an unusual clog out of the room's toilet: a human heart. Eventually he finds a criminal ring that uses immigrants for body parts; they're organ meat in a butcher's window. And unlike the B-picture hysteria of films from the last few years like The Harvest (1993) that tried to wring drama from this idea yet underdramatized the surrounding circumstances, Dirty Pretty Things plays it straight and cool.

And though it has its share of earnest moments, the movie doesn't sink to gaudy moralizing. Knight's climactic story-beat achieves its purpose with a minimum of fuss, abetted by the elegant thoughtfulness of Frears and the no-nonsense charisma of Ejiofor. After watching Frears ply his refined skills in mainstream studio fare, it's enthralling to see him employ that jazziness to spark his ticking impatience with injustice. This is a return to the dancing sympathy that suffused Frears' My Beautiful Laundrette (1985).

This film has a conquering spirit. The dankness is replaced by an optimistic blast of sunlight at the end, a contrast to the earlier lighting dimmed with human misery. Frears blasts away the blight, though he doesn't have to work to restore Okwe's dignity. It shines through from the start.

The canonical shot of an East Asian city is a night skyline studded with towering apartment and office buildings, bright with neon and plastic signage, a landscape of energy and modernity. Another classic image is the same city seen from above, in which identical apartment towers march across the city, spilling out over nearby geography, like stylized soldiers colonizing new territory in a board game. Densely populated dynamic conurbations of money, technological innovation and convenience, it is hard to see the cities of East Asia as what they truly are: necropolises. Why is this? The East Asian development model, with

Desperate dads meet in car parks to exchange packets; exhausted parents slip it into their kids’ drinks; families wait months for prescriptions buy it “off label.” But is it worth the risk? “The first time I gave him a gummy, I thought, ‘Oh my God, have I killed him?’ He just passed out in front of the TV. That never happens.” Jen remembers giving her son, David, six, melatonin to help him sleep. She got them from a friend, a pediatrician who gave them to her own child. “It was sort of hilarious. She had half a tub of gummies,

The wide-screen spectacle of Formula One gets a gleaming, rip-roaring workout in Joseph Kosinski’s F1, a fine-tuned machine of a movie that, in its most riveting racing scenes, approaches a kind of high-speed splendor. Kosinski, who last endeavored to put moviegoers in the seat of a fighter jet in Top Gun: Maverick, has moved to the open cockpits of Formula One with much the same affection, if not outright need, for speed. A lot of the same team is back. Jerry Bruckheimer produces. Ehren Kruger, a co-writer on Maverick, takes sole credit here. Hans Zimmer, a co-composer previously, supplies the thumping

There is an old British curse, “may you live in interesting times,” passed off as ancient Chinese wisdom to make it sound more exotic and profound. We are living in interesting times. From US President Donald Trump’s decision on American tariffs, to how the recalls will play out, to uncertainty about how events are evolving in China, we can do nothing more than wait with bated breath. At the cusp of potentially momentous change, it is a good time to take stock of the current state of Taiwan’s political parties. As things stand, all three major parties are struggling. For our examination of the