The east side of Tokyo's Shinjuku Station is a place with thousands of pubs, karaoke bars, brothels, gigolo clubs and pachinko parlors. It is also a world which has absorbed over 10,000 Taiwanese women over the past two decades, women whose lives have been neglected in the teeming and highly lucrative connection between Taiwan and Japan.

Ling-chien (

When the men come in, she attends to them, pouring wine or whisky, chatting or singing a few songs. If the guests are generous with money, she doesn't mind if they put their hand on her thigh. There might even be a few friendly kisses. Then it's lots of smiling and bowing and calling out her thanks. Just very occasionally, she goes home with a guest.

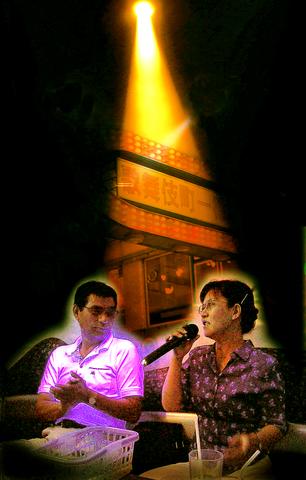

PHOTO COURTESY OF YANG LI-CHOU

"I'm very tired," she says. "This is a land of troubles. If I hadn't been in debt, I would not have come here."

Road to ruin

Ling-chien and Chien-hui (

"When we first got here, money was easy to earn. We earned more than twice what we could in Taiwan. So when my three-month visa came due, I bought a fake marriage certificate so I could keep on working," said Chien-hui.

According to Chien-hui, most of them came to Japan to earn money to take care of their family. Others were heavily in debt back home or had many young siblings to take care of. They usually hoped to make some quick money and return home, but things did not always work out that way.

Earning money was easy. But spending money was also easy. Money lenders where always there to help out, but suicide was sometimes the only way out of their clutches. "Last month, my sister committed suicide because of large debt," said Chien-hui. "Her last words were, `I regret coming to this place.'"

In the blocks of Kabuki Cho in 2002, there were more than 3,000 registered bars and brothels, 1,000 of them owned by Taiwanese.

Shinjuku also has the highest crime rate in Japan. Kabuki Cho registered 5,400 criminal cases in 2002, 40 times more than the average for Tokyo as a whole.

"If you want to survive in Kabuki Cho, you have to play tricks. That's the lesson I've learned over the years," said Fu-dai (富代), a Taiwanese mama-san who owns three bars. "I have opened my own bars. I work 24-7. I grit my teeth and I'll work until I die here. I don't feel ashamed of myself, because I don't steal."

Documenting a hidden life

Ling-chien's life, and that of her Taiwanese sisters has become the subject of a documentary film by Yang Li-chou (

"The thing I thought about most making this film, is that it portrays a version of Taiwan's history in the 1970s," said Yang.

"In the 1970s, many people from Taiwan were sent overseas to study. People such as Boris Chang (

Of the many women living in this world, some have risen to be mama-san, female proprietors of a bar or similar establishment, who run a couple of girls of their own.

One mama-san says in the film: "In a way, it's like we were sent to Japan to serve in the military draft. Taiwanese men take two years to finish, but for us here, it took 20 years. And this is voluntary draft, and there is no retirement."

Looking back 20 years, it's not difficult to find on reports about the wave of Taiwanese prostitutes working in Japan.

An AFP report from March 1980 was one of the first to report on Taiwanese bar girls in Tokyo. It reported the rise in illegal female workers from Taiwan, most of whom where taking jobs as bar girls or strippers. The report cited statistics from Japan's immigration bureau, saying out of the 557 illegal foreign female workers arrested in 1979, 384 were from Taiwan.

According to a United Daily News report the following month (April 1980), the AFP report so shocked the Taiwanese public that the matter was raised by then premier Chiang ching-kuo (

Taiwan had lifted its ban on overseas travel for citizens in 1979. This move opened the floodgates and waves of Taiwanese women headed to Japan to dig for gold in Japan's red-light districts.

News reports on Taiwanese prostitution in Japan became frequent in Taiwan's Chinese-language press, often in the society pages and often related to murder or robbery.

Every month, the police reportedly arrested hundreds of women, travel agents and brokers involved in this trade. Travel agents would often provide fake papers for the women to make them eligible for business visas, allowing a longer stay in Japan.

A Helping hand

Someone Else's Shinjuku East was screened at the 2003 Taipei Film Festival and audience response was strong, as many people were unaware of this chapter in Taiwan's history. Yang and Chu found very little documentation on this group of women when they were doing research for the film.

Wang Fang-Ping (王芳萍), a labor activist from the Collective of Sex Workers and Supporters (日日春關懷互助協會), pointed out that such groups are easily overlooked even on research focusing on the conditions of sex workers.

"We are excited to see the launch of the film. These women are Taiwan's first group of migrant workers. Like the Filipino and Indonesian workers now in Taiwan ... their journey traces the course of globalization. They are actually the vanguard of globalization," said Wang.

Masato (who declined to give his last name) from the Tokyo Sex Worker Movement, said foreign sex workers are much harder to reach. They easily become the most powerless of groups.

"Shinjuku's Kabuki Cho is basically an underworld. It's already hard to reach sex workers and give them assistance," Masato said. "But for foreign sex workers, they are an underground part of the underworld."

The People’s Republic of China (PRC) invaded Vietnam in 1979, following a year of increasingly tense relations between the two states. Beijing viewed Vietnam’s close relations with Soviet Russia as a threat. One of the pretexts it used was the alleged mistreatment of the ethnic Chinese in Vietnam. Tension between the ethnic Chinese and governments in Vietnam had been ongoing for decades. The French used to play off the Vietnamese against the Chinese as a divide-and-rule strategy. The Saigon government in 1956 compelled all Vietnam-born Chinese to adopt Vietnamese citizenship. It also banned them from 11 trades they had previously

Growing up in a rural, religious community in western Canada, Kyle McCarthy loved hockey, but once he came out at 19, he quit, convinced being openly gay and an active player was untenable. So the 32-year-old says he is “very surprised” by the runaway success of Heated Rivalry, a Canadian-made series about the romance between two closeted gay players in a sport that has historically made gay men feel unwelcome. Ben Baby, the 43-year-old commissioner of the Toronto Gay Hockey Association (TGHA), calls the success of the show — which has catapulted its young lead actors to stardom -- “shocking,” and says

Jan. 12 to Jan. 18 At the start of an Indigenous heritage tour of Beitou District (北投) in Taipei, I was handed a sheet of paper titled Ritual Song for the Various Peoples of Tamsui (淡水各社祭祀歌). The lyrics were in Chinese with no literal meaning, accompanied by romanized pronunciation that sounded closer to Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese) than any Indigenous language. The translation explained that the song offered food and drink to one’s ancestors and wished for a bountiful harvest and deer hunting season. The program moved through sites related to the Ketagalan, a collective term for the

Inside an ordinary-looking townhouse on a narrow road in central Kaohsiung, Tsai A-li (蔡阿李) raised her three children alone for 15 years. As far as the children knew, their father was away working in the US. They were kept in the dark for as long as possible by their mother, for the truth was perhaps too sad and unjust for their young minds to bear. The family home of White Terror victim Ko Chi-hua (柯旗化) is now open to the public. Admission is free and it is just a short walk from the Kaohsiung train station. Walk two blocks south along Jhongshan