I spent the whole of this week telling myself to get stuck into this book, but only succeeded in the way you get stuck in a bog or a quagmire.

My final judgment has to be that this unfocused and characterless novel confirms the view that the author's selection for the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2000 was possibly the biggest blunder in the Nobel's entire 101-year history.

When Gao Xingjian won the prize, a remarkable division of opinion emerged.

Some heralded his Soul Mountain as a great novel, but others found it unreadable. Perhaps the English translation was the problem. No, wrote a correspondent from New York in the the Taipei Times -- the Chinese original was also impenetrable.

Dark rumors circulated about the politics within the relevant Nobel committee. And when the Beijing authorities protested they had a hundred better writers in China (Gao has lived in Paris since 1987), some commentators wondered if for once they might not have been right.

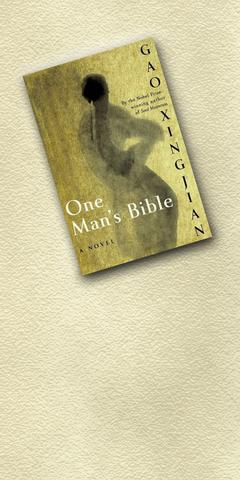

One thing is clear about Gao's new novel, One Man's Bible -- it's as much autobiography as fiction. The central character is a Chinese writer, painter and playwright who lives in France. All these things are true of Gao. In chapter nine, he burns his manuscripts to preserve his anonymity during the Cultural Revolution, and we know Gao did this as well.

Generally, the mix is as in Soul Mountain. The prose is rambling and pedestrian, chapters alternate between the present and the past, and much of the main character's time, in both epochs, is spent lying in bed in the company of various lovers. Even so, and despite its length, this book is slightly tighter, at least in its earlier parts, than its problematic predecessor.

As the novel opens, the main character is in a hotel room in Hong Kong. With him is his German lover, Margarethe. He starts to tell her about his youth in China. The young girl he made love with there had asked him not to penetrate her as she didn't have a license for that, and she was physically checked every year by the authorities.

Memories of China alternate with events, far less dramatic, in Hong Kong.

Mostly it's just talk, and before long the focus is on one subject only -- the Cultural Revolution. For the most part the China chapters concern a cadre-school, a farm where the main character is undergoing forced "re-education through labor," a country school where he teaches, and similar facelessly bleak locations.

He makes love with a biology student called Xu Ying, resists the advances of a middle-school student, and then after emigrating meets Sylvie, from France, who accompanies him on a trip to Australia. He meets a woman whose name he never learns when in Sweden attending a literary conference. And so it goes on.

The Cultural Revolution is these days an unoriginal subject for a book, whether fiction or non-fiction. There have been so many memoirs covering the period you would think authors looking for original topics might prefer to avoid it. But Gao doesn't select, let alone invent, subjects for novels. He simply takes a chunk of his life and narrates it, using "he" instead of "I" for the central figure.

In so far as there is any theme, the terror that characterized the years 1965-1975 is shown as growing out of the characteristics of Chinese communist society as a whole. At that time simple questions from officials such as, "Have you got your work permit?" assumed far more ominous overtones, but the control structure was already in place. It was just waiting to be abused.

For the most part, to Gao's protagonist the Party is a nightmare and the rest of the world inexplicable. He records that his mother was found drowned in a river, causes unknown but under-nourishment suspected. He himself goes to inspect the famous Yellow River and finds only a muddy sludge enclosed by concrete embankments. Was this where Chinese civilization originated, he asks. Had those who sung its praises ever seen it, or had they just made it all up? There doesn't seem to be any redeeming feature to China, whichever way he turns.

In these circumstances, women's bodies become a kind of refuge from terrifying ideological abstractions. Basic and unambiguous, they function as reassuring the central character of his humanity despite the horrors and ugliness around him.

Historically, books about the oppression and heroism of ordinary people have tended to be vigorous stories with strong characters and dramatic events. Famous examples of the genre are Victor Hugo's Les Miserables and Emile Zola's Germinal. But One Man's Bible isn't at all like these. Here the main character looks inwards, not outwards. His other characters are mainly the women he sleeps with, not fellow dissidents. The Cultural Revolution is something terrible he has to hide his head from. The people as a whole are mostly perceived as a pack of mindless dogs, and he can only escape by disguising himself temporarily as one of them.

Seen in this light, Gao Xingjian epitomizes the modern plight of the independent-minded individual under a tyrannical regime which is able to use the malleability of the people themselves as an instrument of its policies.

As such he may be entered in literary history as "significant."

Nevertheless, an autobiographical narrative cannot masquerade as a novel. In real life there are loose ends, things which happen that the individual never understands. But the reader of a work of fiction demands to have ambiguities sorted out, to have loose ends tied up, and for the story to assume some kind of form, however amorphous. This Gao Xingjian appears unable, or unwilling, to do.

Parts of this novel are mildly effective, and the book is an improvement on Soul Mountain in one respect at least -- it's nowhere obscure. But there's no way One Man's Bible is going to be a pleasure to read. The best Gao can hope for is that the work will be judged as symbolic of its era without being in any way enjoyable -- hardly an enviable fate. The book was, incidentally, first published in Chinese here in Taiwan, in 1999.

Last week, on the heels of the recall election that turned out so badly for Taiwan, came the news that US President Donald Trump had blocked the transit of President William Lai (賴清德) through the US on his way to Latin America. A few days later the international media reported that in June a scheduled visit by Minister of National Defense Wellington Koo (顧立雄) for high level meetings was canceled by the US after China’s President Xi Jinping (習近平) asked Trump to curb US engagement with Taiwan during a June phone call. The cancellation of Lai’s transit was a gaudy

Following the shock complete failure of all the recall votes against Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) lawmakers on July 26, pan-blue supporters and the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) were giddy with victory. A notable exception was KMT Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫), who knew better. At a press conference on July 29, he bowed deeply in gratitude to the voters and said the recalls were “not about which party won or lost, but were a great victory for the Taiwanese voters.” The entire recall process was a disaster for both the KMT and the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP). The only bright spot for

From Godzilla’s fiery atomic breath to post-apocalyptic anime and harrowing depictions of radiation sickness, the influence of the nuclear bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki runs deep in Japanese popular culture. In the 80 years since the World War II attacks, stories of destruction and mutation have been fused with fears around natural disasters and, more recently, the Fukushima crisis. Classic manga and anime series Astro Boy is called “Mighty Atom” in Japanese, while city-leveling explosions loom large in other titles such as Akira, Neon Genesis Evangelion and Attack on Titan. “Living through tremendous pain” and overcoming trauma is a recurrent theme in Japan’s

As last month dawned, the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) was in a good position. The recall campaigns had strong momentum, polling showed many Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) lawmakers at risk of recall and even the KMT was bracing for losing seats while facing a tsunami of voter fraud investigations. Polling pointed to some of the recalls being a lock for victory. Though in most districts the majority was against recalling their lawmaker, among voters “definitely” planning to vote, there were double-digit margins in favor of recall in at least five districts, with three districts near or above 20 percent in