There is a lot of bad art probing notions of superficiality, but in a new show called Zoo Part 2, Malaysian-born photographer Hooi-wah Suan (全會華) has managed to discard the cliches and present a subtle, outwardly simple and intensely gratifying take on the normally overplayed theme. It shows at the Taiwan International Visual Arts Center (TIVAC) until Aug. 1.

The exhibition consists of 32 photographs of animals taken at three zoos: Taipei's Mucha Zoo, the Tokyo Zoo and the Paris Zoo. The prints are small, either 5x7s or panoramic 3x9s, and sepia-toned. As objects and in addition to being photographs they are indeed objects, they seem to be both worth cherishing and worth studying, ornaments and documents. They have the quaintness of ceramic collectibles and the remoteness of 19th century documentary photographs. This sensibility of oppositions creates a tension in the photos, both individually and as a series, and out of that tension comes the work's extremely interesting message.

PHOTO COURTESY OF HOOI-WAH SUAN

But before jumping ahead to this "all-important artist's message" -- the subject matter of the photos runs the gamut of standard zoo sights; there is an elephant, a lion, a rhino, an alligator, and so on. It's exactly what a zoo catalogue is supposed to be. And like a hypothetical zoo catalogue, the animals are centered within their picture frames, or rather cubby-holed and encapsulated -- and here's the unique and self-conscious decision of the artist -- by the photographs themselves.

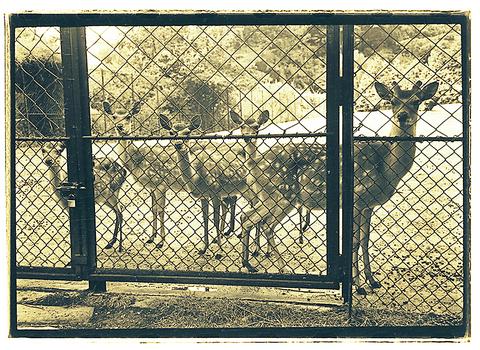

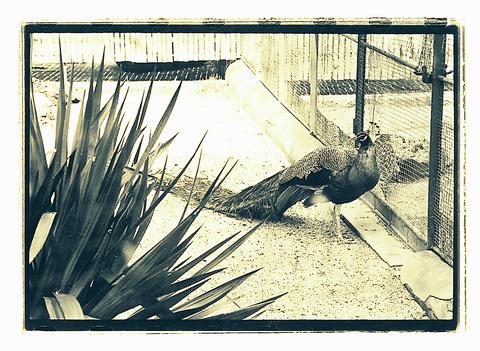

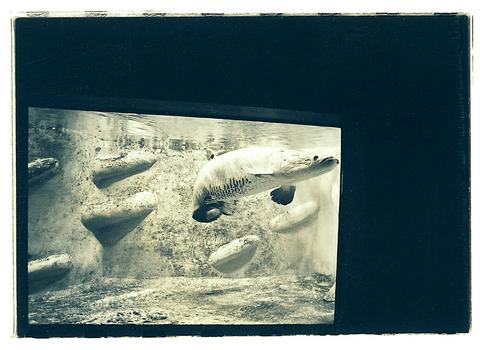

So Suan is able to turn what would otherwise be a simple photo series of zoo animals into something much more philosophical. He takes a group of animals, each of which is caught in the cage of the photograph just as much as it is caught in the cage of the zoo, and uses it to examine the weird relationship between unnatural environments and those who live in them. Only in two of the 32 photos are animals shown without the trappings of their captivity (and I'd say one of those, a shot of birds silhouetted against a sunset, is an anomaly and should have been omitted). Deer stare from behind a fence; a fish swims in a tank; primates stare at rope swings; and flamingos parade in a field, where alas, there is a stone wall in the distance behind them. A few pictures focus simply and exclusively on the zoos' environments in themselves -- a birdless birdhouse with a forest mural for a back wall, a monkey gym with no monkeys.

Like modern masters Hiroshi Sugimoto, who photographed both wax museum personages and wildlife dioramas in natural history museums, and Sherry Levine, who photographed other photographs, Suan is able to use his photos to look closely at the nature of artificiality. The environments of zoos are simulated, yet the animals are real, and as real animals, must interact with their environments. In that sense, zoos possess a real (not an artificial) ecology. So who is not to say that zoos, these animal museums, do not count as "natural habitats"? Unlike the swarming shutterbugs that undoubtedly surrounded Suan at the zoos where he photographed, he decided not to crop out the cages, fences and moats and perpetuate the illusion that the animals live in their ancestral jungles, plains and forests. Instead, he presents them as being in Tokyo, Paris and Taipei -- location names that serve as the only basis for the title of each photo.

Like all sincere art, Suan's photos ask questions. What does it mean to live in an artificial environment or a simulated environment? What does it mean when your environment is derived conceptually from something either far away or that no longer exists? And the interesting thing about these questions is that they apply just as well to the penguins of Taipei as they do to the citizens of Taipei. So perhaps it is little wonder that Zoo Part 2 was more than half sold out by its second day.

TIVAC is at 29 Liaoning St., Lane 45, No. 29, 1F (遼寧街45巷29號1樓).

Zines with a reason

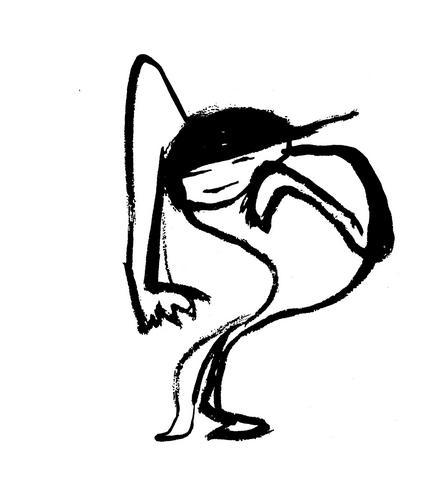

In Taipei there isn't any real venue for outsider art, or art that is both untrained and operates outside the institutions of galleries and museums. So it pops up here and there, usually in restaurants and cafes. A noteworthy show up now is Floaty, a group of expressive line illustrations and drawings by American Keith Saunders.

Saunders began drawing Floaty in 1995, photocopying his collections and binding them into small books or zines. Subsequently, he's used these artist books as goodwill gestures while traveling, and in recent years he's sold them at modest prices (NT$150 per book in the current show), devoting all the profits to a friend, Cory Howard, who is fighting breast cancer.

The drawings ride the edge between playful and demented and make fun with the archetypes of the contemporary world: there are office workers stabbing themselves with pencils, smiling girls dancing, devils with pitchforks and fat girls at the beach. The two volumes on sale now were both produced while Saunders was living in Taiwan and contain subjects pulled from local inspiration. They're also for a very good cause.

You can see Floaty at Norwegian Wood (挪威森林咖啡館) on Roosevelt Rd., Sec. 3, Lane 284, No. 9 (羅斯福路3段284弄9號) until Aug. 6. You can also see Saunder's work on a larger scale in the new wall and ceiling murals that he's in the process of painting at Underworld (

On April 26, The Lancet published a letter from two doctors at Taichung-based China Medical University Hospital (CMUH) warning that “Taiwan’s Health Care System is on the Brink of Collapse.” The authors said that “Years of policy inaction and mismanagement of resources have led to the National Health Insurance system operating under unsustainable conditions.” The pushback was immediate. Errors in the paper were quickly identified and publicized, to discredit the authors (the hospital apologized). CNA reported that CMUH said the letter described Taiwan in 2021 as having 62 nurses per 10,000 people, when the correct number was 78 nurses per 10,000

As we live longer, our risk of cognitive impairment is increasing. How can we delay the onset of symptoms? Do we have to give up every indulgence or can small changes make a difference? We asked neurologists for tips on how to keep our brains healthy for life. TAKE CARE OF YOUR HEALTH “All of the sensible things that apply to bodily health apply to brain health,” says Suzanne O’Sullivan, a consultant in neurology at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery in London, and the author of The Age of Diagnosis. “When you’re 20, you can get away with absolute

May 5 to May 11 What started out as friction between Taiwanese students at Taichung First High School and a Japanese head cook escalated dramatically over the first two weeks of May 1927. It began on April 30 when the cook’s wife knew that lotus starch used in that night’s dinner had rat feces in it, but failed to inform staff until the meal was already prepared. The students believed that her silence was intentional, and filed a complaint. The school’s Japanese administrators sided with the cook’s family, dismissing the students as troublemakers and clamping down on their freedoms — with

As Donald Trump’s executive order in March led to the shuttering of Voice of America (VOA) — the global broadcaster whose roots date back to the fight against Nazi propaganda — he quickly attracted support from figures not used to aligning themselves with any US administration. Trump had ordered the US Agency for Global Media, the federal agency that funds VOA and other groups promoting independent journalism overseas, to be “eliminated to the maximum extent consistent with applicable law.” The decision suddenly halted programming in 49 languages to more than 425 million people. In Moscow, Margarita Simonyan, the hardline editor-in-chief of the