Like many exiled or oversea Chinese authors such as Gao Xingjian (高行健) or Ha Jin (哈金), Dai Sijie (戴思杰) creates his art in a second language, earning acclaim in the Western world. But back in China, those works are almost always banned for failing to conform to the Communist Party line. But, for his part, Dai has long forsaken politics.

Balzac and the Little Chinese Seamstress (reviewed in Taipei Times on Oct. 21 last year) is the best-selling novel by Dai, who is perhaps better known as a filmmaker.

"It's nothing but a love story," he said in an interview with Taipei Times.

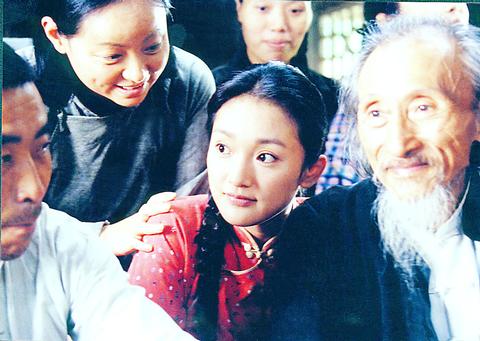

PHOTO: YU SEN-LUN, TAIPEI TIMES

Originally written in French and published in more than 30 countries, Dai has brought this partly autobiographical story of his boyhood memories to the screen. The film was selected as the opening film for the Un Certain Regard section at this year's Cannes film festival.

Last Thursday evening, the opening day for the Un Certain Regard selection of films, a blue carpet was rolled out in front of the Claude Debussy Theater and the air was filled with Chinese Cultural Revolution propaganda songs. "We are the little red guards of Chairman Mao... We travel from the mountains to praise him..." -- a bizarre scene to behold on the French Riviera.

Two faces familiar to Taiwanese audiences -- Zhou Xun (周迅), the starlet of Suzhou River, and Liu Ye (劉燁), who won a Golden Horse Best Actor for the film Lan Yu (藍予) -- star in Balzac, which is set in the 1970s in a mountainous village in Sichuan Province. Two young men, Duo and Dai, labeled as sons of "reactionary intellectuals" are sent to a far-flung outpost of Maoist re-education where 99 percent of the village is illiterate. There they are forced to carry manure for the farms and work in the coal fields so that they might "learn from the brave working class," as their re-education chief tells them.

PHOTO COURTESY OF DAI SIJIE

The only fun activity they are able to think up is to play Mozart on Dai's violin, creating their own lyrics in praise of Mao Zedong (毛澤東).

They also try to tell clever folk stories to amuse the villagers and the chief, which buys them a precious few hours of freedom to go to the nearby town to watch melodramatic propaganda films from North Korea. They'd then return to their village and retell these stories to the culture-starved locals.

One day they meet a very pretty girl in the village who is a seamstress. "She's a bit rustic. I want to change her," Luo tells Dai. Stealing a whole suitcase of banned books from a good friend, the two began to court the seamstress through daily reading and storytelling sessions of Flaubert, Tolstoy, Hugo, and the most compelling to them, Balzac.

The power of literature in the film is like magic, and breathes life into both the trio's relationship and the imagination of the whole village. The chief smiles more and productivity increases. In this village full of steep cliffs, hills and valleys, they read and tell stories in a secret cave where they hide their books.

More than 20 years pass. Dai becomes a violinist in France but returns to the village, which is being evacuated due to the construction of a large dam on the Yangtze River. The village is about to be inundated, but Dai is desperate to find the little seamstress, who abruptly left when she fell in love with Luo.

"There was a real love story," Dai said of the autobiographical aspects of the story, "but not as romantic. The stealing books part is true and the experience of reading stories to farmers is also true."

From the 1960s to 1970s, during Dai's teenage days, "all the books were banned, even science books. ... So at that time almost everybody stole books and hid them," he said.

"I wanted to show how much impact culture could have on an isolated mountain village, and especially for [the seamstress]. It was a revelation of freedom, of self-consciousness. The little seamstress had seen more in Balzac ... learned that men could flirt with women, that it is natural. ... This is what she had never learned during her days of being indoctrinated ... that life could be filled with many nice things," he said.

For Dai, this lack of freedom and individualism is the essence of his generation.

The film was shot with beautiful Sichuan as its background, excellent actors and sophisticated, evenhanded storytelling. The French-financed Balzac, is a comeback work for Dai, who has spent 15 years making French-language films. His Chinese Sorrow won acclaim at the Locrano and Cannes Film Festivals.

As to how a young woman could suddenly be changed through foreign literature -- the part of the story most criticized by Chinese authorities and the main reason the story was not released in China -- Dai has an apolitical answer.

"The influence of literature is universal. [The story] was not only an ode to the literature we had read, but also simply to show that in a difficult situation, we, at that young age, had a yearning to learn, to see new things and nice things," Dai said.

The Chinese-language version of Balzac and the Little Chinese Seamstress will be published in Taiwan by Crown Publishing. And the film will be release in Taiwan soon.

June 2 to June 8 Taiwan’s woodcutters believe that if they see even one speck of red in their cooked rice, no matter how small, an accident is going to happen. Peng Chin-tian (彭錦田) swears that this has proven to be true at every stop during his decades-long career in the logging industry. Along with mining, timber harvesting was once considered the most dangerous profession in Taiwan. Not only were mishaps common during all stages of processing, it was difficult to transport the injured to get medical treatment. Many died during the arduous journey. Peng recounts some of his accidents in

“Why does Taiwan identity decline?”a group of researchers lead by University of Nevada political scientist Austin Wang (王宏恩) asked in a recent paper. After all, it is not difficult to explain the rise in Taiwanese identity after the early 1990s. But no model predicted its decline during the 2016-2018 period, they say. After testing various alternative explanations, Wang et al argue that the fall-off in Taiwanese identity during that period is related to voter hedging based on the performance of the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP). Since the DPP is perceived as the guardian of Taiwan identity, when it performs well,

The Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) on May 18 held a rally in Taichung to mark the anniversary of President William Lai’s (賴清德) inauguration on May 20. The title of the rally could be loosely translated to “May 18 recall fraudulent goods” (518退貨ㄌㄨㄚˋ!). Unlike in English, where the terms are the same, “recall” (退貨) in this context refers to product recalls due to damaged, defective or fraudulent merchandise, not the political recalls (罷免) currently dominating the headlines. I attended the rally to determine if the impression was correct that the TPP under party Chairman Huang Kuo-Chang (黃國昌) had little of a

At Computex 2025, Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang (黃仁勳) urged the government to subsidize AI. “All schools in Taiwan must integrate AI into their curricula,” he declared. A few months earlier, he said, “If I were a student today, I’d immediately start using tools like ChatGPT, Gemini Pro and Grok to learn, write and accelerate my thinking.” Huang sees the AI-bullet train leaving the station. And as one of its drivers, he’s worried about youth not getting on board — bad for their careers, and bad for his workforce. As a semiconductor supply-chain powerhouse and AI hub wannabe, Taiwan is seeing