When the Ministry of Transportation and Communications' (MOTC) Department of Post and Telecommunications and the Government Information Office (GIO) announced plans for a rigid clampdown on pirate radio stations in March this year, it was viewed as many as a yet another futile battle in the governments' eight-year-old war on pirate broadcasters.

For its geographical size, Taiwan has an extraordinarily large number of pirate stations. Since 1997, the MOTC has closed down 748 pirate radio stations.

PHOTO COURTESY OF TCM

Many more stations have avoided detection either by broadcasting from vans, and sometimes even cars, or simply by remaining one step ahead of the law by intermittently moving their transmitters. While no solid figure exists as to the actual number of pirate stations operating in Taiwan, a recent report estimated the number to be roughly 200 broadcasting on FM channels. A sizable figure when compared to the number of legally licensed stations, which at present number 174 FM stations.

"Although the problem first began to materialize almost a decade ago, it has become more evident over the past couple of years. We've either discovered or have been informed of literally hundreds of pirate radio stations in recent years," said Yao Ping-chung (姚秉忠), section chief of the MOTC's Department of Post and Telecommunications.

The problem is now so widespread, that national radio stations such as ICRT and Hit FM, along with regional stations like Voice of Taipei (台北之音) receive reports on an almost daily basis from listeners complaining about pirate radio station interference.

"Managing the public airwaves and ensuring that pirate stations don't appear is a problem. Historically, ICRT has seen most of its problems in the Taichung area," said ICRT's station manager, Doc Casey. "But that's not to say there aren't such problems with [pirate] stations broadcasting in northern Taiwan."

Not so long ago, the ICRT station manager discovered pirate radio in his own backyard. Returning home one evening to discover that both his television and radio were encountering very strong interference, Casey looked out of his window only to be confronted by the sight of an antenna perched on top of the residential building directly opposite his own.

"You can stop [pirate stations] one day, but then the next week they're back broadcasting again," explained Eric Liang (梁序倫), vice general manger of Voice of Taipei, one of the first radio stations to be granted a license following the governments opening of the airwaves. "It's an endless task and one that is becoming increasingly hard to control, especially in the south of Taiwan where enforcement is lax."

According to Liang, pirate radio stations are allowed to prosper in the south due to their distance from Taipei.

"Stations in Chiayi for example are far enough away from Taipei for authorities to be able to simply ignore," Liang said. "When they don't effect the capital city proper a `who cares' attitude seems to be taken by all concerned."

Taiwan's pirate broadcasters began hitting the airwaves in 1994, shortly after the government opened radio channels to the public. Although a handful of stations applied for licenses, a large number refused to due to the strict guidelines laid down by the GIO regarding program content.

"Sure, it was a nice gesture. But when you say you're going to allow the public free access to an area of the media and then say `but we're still going to monitor what you say,' it was a half-hearted attempt and a real non-starter," said Hengchun Chi (恆春兮), a pirate broadcaster in Kaohsiung between 1995 and 1996.

Pirate radio stations' anti-KMT stance proved hugely popular. Hotlines of stations such as The Voice of Taiwan (台灣之聲) -- a station now broadcasting legally -- one of the most candid of Taiwan's early pirate radio stations, were overwhelmed with callers representative of all walks of life eager to comment on social issues and political events of the day.

The KMT suddenly found itself the target of uncensored on-air criticism, as the nation found a medium from which to vent its frustration over 40 years of government control.

"Shrill, funny, irrelevant and occasionally scurrilous, it insults the mighty and defends the meek," was how one news agency described the Voice of Taiwan.

Needless to say, the government didn't find the content of the Voice of Taiwan and other such pirate radio stations either funny or irrelevant. On Aug. 1 of 1994, it utilized over 6,000 policemen and a couple of helicopters in an early morning attempt to shutdown 14 pirate stations operating in the Taipei metropolitan area.

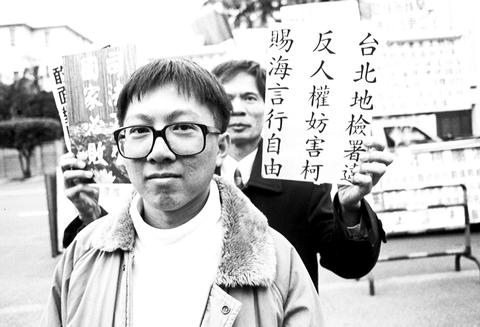

The raids didn't go as planned, however. A minor altercation between pro-democracy activists, radio station staff and the security forces broke out in the streets adjacent to the Presidential Building.

After the dust had finally settled only handful of the pirate stations had been successfully taken off air. Other stations were inundated with calls from listeners, anxious to make cash donations in order to help pay the stations' legal fees.

"I wouldn't go as far as to call it a riot. Obviously it was heated, but then it was very traumatic time in Taiwan's path to democratization and such displays of anti-government sentiment were often labeled as riots," said Jiang Hui-ting (姜慧婷), spokesperson for Formosa Hakka Radio (寶島客家電台), a station that prior to its' licensing in 1996, broadcast illegally under the name The New Voice of Formosa (寶島新聲客家電台). "However you refer to the demonstrations, the actions did make the government sit up and realize that it needed to relax the broadcasting law."

In the wake of mild revisions to the Broadcast and Television Law (廣播電視法) in 1996, the political voice of pirate radio all but disappeared. Latter-day pirates of the airwaves have instead turned their attention to the promotion of manufactured products rather than thought-provoking political views.

What was once a clandestine, but glamorous podium from which pro-democracy activists voiced their grievances has instead become a medium for bad karaoke and sales of medicinal cure-alls.

"It's certainly been an about-face. I mean, selling medicines and holding karaoke contests couldn't be further removed from politics," said Chi, the once outspoken host of pirate talk show radio who now makes a living releasing CDs and holding concerts parodying pirate radio. "I see nothing wrong with this. The karaoke shows get hundreds of callers and people actually purchase the medicines regardless of their pharmaceutical value."

One of the main reasons successive government clampdowns have proven so ineffective is due to the lenient manner in which courts deal with violators of the Broadcast and Television Law. "The problem of enforcing the law is two-fold. The money available to finance enforcement is too little and the penalties the courts are imposing are not sufficient enough to deter people," Casey said. "The MOTC needs more money if it is to track down violators and prosecute them."

Although the government has managed to pull the plug on 29 pirate radio stations since the clampdown began in March, those caught in the dragnet will quite possibly be broadcasting again within a very short time. Neither the confiscation of equipment nor penalties dished out by the courts are considered strong enough deterrents to put an end to the increasingly lucrative business of pirate radio.

When the government first began cracking down on pirate radio in the early 1990s, station owners faced fines of as little as NT$22,600. Almost a decade later the penalty for the illegal use of broadcasting equipment stands at NT$100,000, which is not enough to put out of business operators who can earn upwards of NT$200,000 per month.

Along with modest fines, another loophole that allows pirate radio stations to continue operations even after prosecution is the exemption period imposed by courts on pirate radio operators. Once proven guilty of violating the broadcast law, operators are automatically granted a 30-days exemption from further prosecution or fines. A period of time in which operators are free to broadcast their pirate missives without fear of further prosecution.

"We pay tax, pay our licensing costs and abided by the law, but we're still plagued with people poaching wavelengths near ours and interfering with our reception," Liang said. "What really caps it off, though, is that when they get caught many operators scream foul and accuse the courts of being undemocratic and not allowing free speech. I mean, free speech? These people are not selling a concept or entertainment but a product."

Regardless of whether pirate radio in Taiwan is a form of free speech or not, the headaches look set to continue for both Taiwan's 174 legal radio stations and the MOTC.

Earsplitting karaoke enjoyed by those with Kevlar eardrums and programs selling snake oil will continue to plague the airwaves, generating both profit and audiences -- however inane the content or product.

"A friend of mine heard a program one evening on which the presenter was selling a potion that would supposedly make a dead person twitch and move about," said the ex-pirate radio host. "I don't know what's more unbelievable? The medicine itself, or the scores of people who were actually spent the NT$3,500 to purchase it?"

On April 26, The Lancet published a letter from two doctors at Taichung-based China Medical University Hospital (CMUH) warning that “Taiwan’s Health Care System is on the Brink of Collapse.” The authors said that “Years of policy inaction and mismanagement of resources have led to the National Health Insurance system operating under unsustainable conditions.” The pushback was immediate. Errors in the paper were quickly identified and publicized, to discredit the authors (the hospital apologized). CNA reported that CMUH said the letter described Taiwan in 2021 as having 62 nurses per 10,000 people, when the correct number was 78 nurses per 10,000

As we live longer, our risk of cognitive impairment is increasing. How can we delay the onset of symptoms? Do we have to give up every indulgence or can small changes make a difference? We asked neurologists for tips on how to keep our brains healthy for life. TAKE CARE OF YOUR HEALTH “All of the sensible things that apply to bodily health apply to brain health,” says Suzanne O’Sullivan, a consultant in neurology at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery in London, and the author of The Age of Diagnosis. “When you’re 20, you can get away with absolute

May 5 to May 11 What started out as friction between Taiwanese students at Taichung First High School and a Japanese head cook escalated dramatically over the first two weeks of May 1927. It began on April 30 when the cook’s wife knew that lotus starch used in that night’s dinner had rat feces in it, but failed to inform staff until the meal was already prepared. The students believed that her silence was intentional, and filed a complaint. The school’s Japanese administrators sided with the cook’s family, dismissing the students as troublemakers and clamping down on their freedoms — with

As Donald Trump’s executive order in March led to the shuttering of Voice of America (VOA) — the global broadcaster whose roots date back to the fight against Nazi propaganda — he quickly attracted support from figures not used to aligning themselves with any US administration. Trump had ordered the US Agency for Global Media, the federal agency that funds VOA and other groups promoting independent journalism overseas, to be “eliminated to the maximum extent consistent with applicable law.” The decision suddenly halted programming in 49 languages to more than 425 million people. In Moscow, Margarita Simonyan, the hardline editor-in-chief of the