After gaining acclaim in the fields of fashion and nude photography, Australian photographer James Houston turned to observing dance. As a great piece of choreography does not necessarily make a great photograph, Houston invited members of three of Australia's leading dance companies -- the Australian Ballet, the Sydney Dance Company and the Bangarra Dance Theatre -- to his studio "to direct my own ideas rather than just shoot predictable `dance shots' that have been used to capture dancers for years."

The results of exposing 600 rolls of black-and-white film over five days are displayed in the Rawmoves exhibition at Cherng Pin Gallery on Tunhua South Rd., as well as an NT$1,750 book with the same title.

As Houston is mainly known as a body and nude photographer -- culminating in an earlier book, Raw, and the official calendar for the 2000 Sydney Olympic Games -- it should come as no surprise that he focuses mainly on the dancers' forms.

PHOTO COURTESY OF THE AUSTRALIAN COMMERCE AND INDUSTRY OFFICE

"I didn't want it to be just about dance. I wanted it to be different. I wanted ... to create images and compositions that captured emotion and form," Houston says in his Rawmoves book.

It is debatable, however, how much of a dancer's emotion a photographer can capture when directing the subject in a studio for one or two days, especially when one lacks a background in choreography (Houston studied ceramic, sculpture and design and took up photography as a hobby 10 years ago).

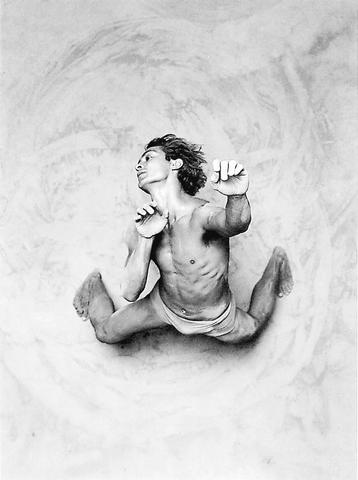

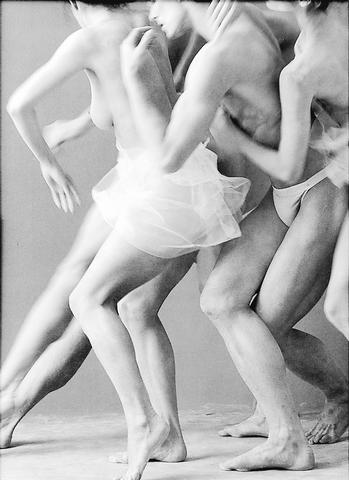

In the roughly 40 prints that are exhibited, Houston shows excellence in technique as well as in capturing dancers when airborne. Most of the group compositions, however, show a lack of choreography, with limbs interlocking to little effect.

PHOTO COURTESY OF THE AUSTRALIAN COMMERCE AND INDUSTRY OFFICE

In the series on the Australian Ballet, placing less importance on the human form and more on costumes might have improved the works, as well as providing more of a variety to Rawmoves.

Despite this, Rawmoves provides an interesting, if highly personal, snapshot of the contemporary dance scene in Australia, which is enhanced by videos of performances by the three groups that are shown in the gallery throughout the day.

Taiwan can often feel woefully behind on global trends, from fashion to food, and influences can sometimes feel like the last on the metaphorical bandwagon. In the West, suddenly every burger is being smashed and honey has become “hot” and we’re all drinking orange wine. But it took a good while for a smash burger in Taipei to come across my radar. For the uninitiated, a smash burger is, well, a normal burger patty but smashed flat. Originally, I didn’t understand. Surely the best part of a burger is the thick patty with all the juiciness of the beef, the

The ultimate goal of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is the total and overwhelming domination of everything within the sphere of what it considers China and deems as theirs. All decision-making by the CCP must be understood through that lens. Any decision made is to entrench — or ideally expand that power. They are fiercely hostile to anything that weakens or compromises their control of “China.” By design, they will stop at nothing to ensure that there is no distinction between the CCP and the Chinese nation, people, culture, civilization, religion, economy, property, military or government — they are all subsidiary

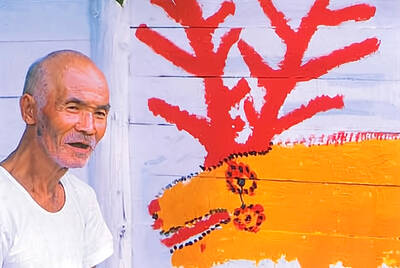

Nov.10 to Nov.16 As he moved a large stone that had fallen from a truck near his field, 65-year-old Lin Yuan (林淵) felt a sudden urge. He fetched his tools and began to carve. The recently retired farmer had been feeling restless after a lifetime of hard labor in Yuchi Township (魚池), Nantou County. His first piece, Stone Fairy Maiden (石仙姑), completed in 1977, was reportedly a representation of his late wife. This version of how Lin began his late-life art career is recorded in Nantou County historian Teng Hsiang-yang’s (鄧相揚) 2009 biography of him. His expressive work eventually caught the attention

This year’s Miss Universe in Thailand has been marred by ugly drama, with allegations of an insult to a beauty queen’s intellect, a walkout by pageant contestants and a tearful tantrum by the host. More than 120 women from across the world have gathered in Thailand, vying to be crowned Miss Universe in a contest considered one of the “big four” of global beauty pageants. But the runup has been dominated by the off-stage antics of the coiffed contestants and their Thai hosts, escalating into a feminist firestorm drawing the attention of Mexico’s president. On Tuesday, Mexican delegate Fatima Bosch staged a