As hustings for the Legislative Yuan's 225 contested seats begin their final week, Taiwan's many local factions (地方派系) have been making news headlines. These factions are notorious for their ability to mobilize voters through illegal means -- mostly by buying votes with cash or gifts -- to get their candidates elected. The going rate for a promise to vote for a certain candidate is NT$500. Although the Ministry of Justice has claimed that prosecutors and police have uncovered a record number of vote-buying cases during this campaign season, the fruits of their efforts remain to be seen.

It's become common knowledge that funds to buy votes roll to constituencies in the final few days before voters go to the polls -- Saturday, Dec. 1, in this case -- and so this coming week will be critical for all candidates, clean and corrupt alike. According to estimates by Li Hsi-kun (李錫錕), a former legislative candidate and now a professor at National Taiwan University (台灣大學), the success rate for buying votes in Taipei County is around 30 percent. In other areas around the nation it can be as high as 50 percent. As an old Taiwanese saying goes: "You don't need a mentor in an election, you just need to buy your way in."

For a candidate in Taipei County, 35,000 votes will nearly guarantee a seat in the legislature. So if the candidate is certain that he or she can obtain at least 10,000 votes from legitimate supporters, they need only to purchase another 25,000 votes to ensure victory.

But the buck doesn't stop there. In order to deliver the NT$500 "reward money" per vote to the hands of willing voters, the candidate has to pay a NT$200 fee to the delivery person, putting the cost of a single vote at NT$700. For a candidate to purchase 25,000 votes in his constituency, he would have to spend NT$17.5 million. But because the candidate's investment would have only a 30 percent success rate, he or she would need to pay off at least 84,000 voters, bringing their total investment to nearly NT$59 million (US$1.7 million) to win the election.

It is mostly through these large cash transactions in district banks that law enforcement agencies are able to monitor vote-buying activities and make arrests.

Factions' role

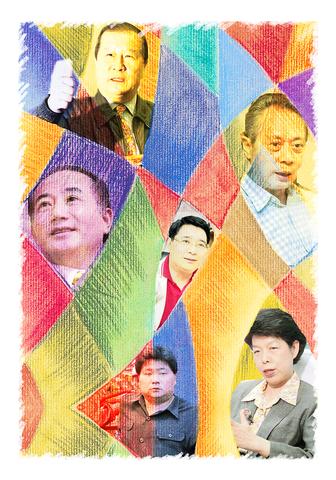

PHOTO: REUTERS

For this large amount of money to be delivered in a very short period of time without being detected, the ill-intentioned candidate must depend on long-established distribution channels and manpower provided by affiliated faction members. Besides casting their own votes for the candidate, this is where political factions contribute the most to their nominee.

From 1945 until last year, when Taiwan was under KMT rule, these local-level political factions traditionally sided with the ruling party to compete against opposition forces such as the DPP and its sympathizers. Thus, vote-buying was tolerated and sometimes even encouraged by KMT officials in order to ensure majority control of the legislature. It is also commonly known that the KMT would offer large sums of money to their candidates in order to facilitate their campaigns. Anywhere from NT$20 million to NT$80 million would be given, depending on the candidate's relationship with the party chief -- amounts far exceeding what the law allows.

According to a recent count, there are approximately 90 local-level factions active in Taiwan (see charts). Spread throughout Taiwan, these factions are staunch supporters of the KMT and, thus, had contributed tremendously to the long years of KMT rule.

PHOTO: REUTERS

The tradition of Taiwan's political factions date back to the Japanese colonial period between 1895 and 1945, when prominent figures such as Lin Hsien-tang (林獻堂), Yang Chao-chia (楊肇嘉), Chiang Wei-chuan (蔣渭川) and Hsu Ping (許丙) led Taiwanese to struggle for political freedom.

The tradition evolved following the change from Japanese to KMT rule after World War II. Through shrewd manipulation and by providing material incentives, the KMT was able to turn most factions away from the call for political and social reform. Step by step, they were led into profit-seeking family politics, often with sons or close relatives inheriting leadership of the faction.

Out of control

PHOTO: REUTERS

A study led by Professor Chen Ming-tong (陳明通) at National Taiwan University indicates that the KMT's own campaign mechanisms accounted for only 25 percent of all the votes gained by the party in the past. The remaining 75 percent were garnered by often unwieldy local-level political factions operating independent of party control.

Frustrated by their lack of success in reeling in these factions, the KMT attempted to remedy the situation during Chiang Ching-kuo's (蔣經國) administration from 1976 to 1988. During that time, the party implemented four strategies designed to gain full control of the political factions.

First, the KMT refused to re-elect members of the legislature and the National Assembly, citing its legitimacy of rule as provided by the Republic of China Constitution of 1947. By so doing, all prominent Taiwanese political figures would be limited to the local level of government. The KMT's ruling power would, therefore, never be threatened.

The party also applied the colonial dictum of divide and rule by introducing new political factions wherever necessary. This policy ensured that every county and city in Taiwan had at least two contending political forces subservient to KMT command. Such a policy, regrettably, sowed seeds of contention in Taiwan's political arenas and became the root of much of the social discord that sprouts up today.

Third, under the KMT government's special arrangement, local factions were allowed to operate financial institutions such as district banks, credit cooperatives and farmers' and fishermen's associations " and their leaders were offered low-rate bank loans. Contracts for local construction projects usually fell into their hands as well. The economic incentives were enormous if they showed their loyalty to the ruling KMT.

Lastly, the KMT would simply recruit their own cadres to replace faction leaders who would not toe the party line. In 1977, Chiang enforced this policy to the extreme by nominating 17 non-factional party cadres to run for commissioner in each of Taiwan's 20 counties. His true intent was too transparent, however, and the plan backfired in that year's election. Supporters of then commissioner of Taoyuan County, Hsu Hsin-liang's

Drastic measures

Chiang's experience prompted him to make a decision which would redraw Taiwan's political map in a rather amusing way. In 1984, he hand-picked Lee Teng-hui (李登輝) to run as vice-president and replace Hsieh Tong-min (謝東閔), whose younger brother had been involved in a series of financial scandals. Meanwhile, a more senior member in Chiang's cabinet, Lin Yang-kang (林洋港), lost his bid for the post mainly because he was a prominent factional figure in Nantou County. By contrast, Lee came from a simple farming family and was educated at National Taiwan University and Cornell Univeristy in the US before becoming mayor of Taipei, a post which would become a major stepping stone in his political career.

With the lifting of martial law in 1987, almost everything became possible for the political factions in Taiwan. In 1992, two heavyweight faction leaders, Liu Sung-pan (劉松藩) from Taichung County's Red faction and Wang Jin-pyng (王金平) from Kaohsiung County's White faction, both marched into the legislature to take up the positions of speaker and deputy speaker respectively.

Nonetheless, the factions' sunny days lasted only until opposition forces gained momentum and began calling for social and political reforms. Local-level factions' influence ebbed last year when loyalties were torn between two contending KMT candidates for president, Lien Chan (連戰) and James Soong (宋楚瑜). The sole DPP candidate, Chen Shui-bian (陳水扁), benefitted from the KMT schism and came away with less than 40 percent of the total popular vote, just enough to win the presidency.

When the DPP came to power last year, some faction leaders quickly shifted loyalty. More importantly, their means of sucking up local financial resources -- district banks, credit cooperatives and farmers' and fishermen's associations -- were cut off by the DPP government through various policy changes. Many corrupt faction leaders such as Legislator Kuo Ting-chai

As soon as their financial base is gone and with the help of law enforcement agencies, Taiwan's local-level political factions might never be the same. It is possible they will take a different attitude toward public affairs and become reform-minded civic groups.

As their role as a means to buy votes in elections becomes more constrained however, factions might also find other ways to exercise power at the local level. Whatever the outcome, they have no choice but to change with the tune of Taiwan's shifting political landscape.

June 23 to June 29 After capturing the walled city of Hsinchu on June 22, 1895, the Japanese hoped to quickly push south and seize control of Taiwan’s entire west coast — but their advance was stalled for more than a month. Not only did local Hakka fighters continue to cause them headaches, resistance forces even attempted to retake the city three times. “We had planned to occupy Anping (Tainan) and Takao (Kaohsiung) as soon as possible, but ever since we took Hsinchu, nearby bandits proclaiming to be ‘righteous people’ (義民) have been destroying train tracks and electrical cables, and gathering in villages

Swooping low over the banks of a Nile River tributary, an aid flight run by retired American military officers released a stream of food-stuffed sacks over a town emptied by fighting in South Sudan, a country wracked by conflict. Last week’s air drop was the latest in a controversial development — private contracting firms led by former US intelligence officers and military veterans delivering aid to some of the world’s deadliest conflict zones, in operations organized with governments that are combatants in the conflicts. The moves are roiling the global aid community, which warns of a more militarized, politicized and profit-seeking trend

The wide-screen spectacle of Formula One gets a gleaming, rip-roaring workout in Joseph Kosinski’s F1, a fine-tuned machine of a movie that, in its most riveting racing scenes, approaches a kind of high-speed splendor. Kosinski, who last endeavored to put moviegoers in the seat of a fighter jet in Top Gun: Maverick, has moved to the open cockpits of Formula One with much the same affection, if not outright need, for speed. A lot of the same team is back. Jerry Bruckheimer produces. Ehren Kruger, a co-writer on Maverick, takes sole credit here. Hans Zimmer, a co-composer previously, supplies the thumping

Dr. Y. Tony Yang, Associate Dean of Health Policy and Population Science at George Washington University, argued last week in a piece for the Taipei Times about former president Ma Ying-jeou (馬英九) leading a student delegation to the People’s Republic of China (PRC) that, “The real question is not whether Ma’s visit helps or hurts Taiwan — it is why Taiwan lacks a sophisticated, multi-track approach to one of the most complex geopolitical relationships in the world” (“Ma’s Visit, DPP’s Blind Spot,” June 18, page 8). Yang contends that the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) has a blind spot: “By treating any