As befits today's post-boom economy, antique Chinese furniture stores in Taipei are offering more affordable and diverse items than when they first emerged about 10 years ago.

Taiwanese consumers began to show fervent interest in antique Chinese furniture in the early 1990s, when the country's stock index reached dizzying heights and generated a new class of nouveau riche among whom collecting antique furniture became something of a fad.

The interest in antique furniture has not waned, but the lavish spending on the most expensive pieces has tapered off considerably, according to local antique dealers.

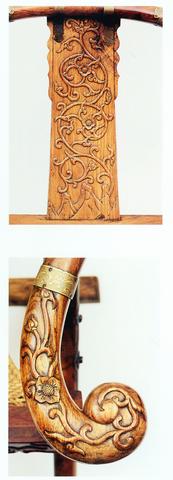

PHOTO: COURTESY OF JEFF HSU'S ORIENTAL ART

Most antique furniture pieces currently on the market originate from the Ming (1368-1644) and Ching (1644-1911) dynasties, the most coveted being from royal and wealthy families and made of such rare hardwoods as red sandalwood, called Zitan (紫檀), and golden rosewood, called Huanghuali (黃花梨).

"It's hard to estimate how big the market is, but it started 10 years ago, and it's getting more mature," says Jeffery Chen (陳仁毅), general manager of Art of Chen (雅典集) in downtown Taipei. Chen said Zitan and Huanghuali items are several times more expensive than when they first showed up on the market, because they are now so scarce.

PHOTO: COURTESY OF JEFF HSU'S ORIENTAL ART

When the store opened 12 years ago, Art of Chen focused on fine Zitan and Huanghuali items, but as prices soared and the economy slowed, the store responded by opening a branch with more affordable pieces made mostly of softwoods like elm. Instead of paying over NT$500,000 for a piece of Zitan furniture, lay collectors could pick up a Ching dynasty elm chair for just NT$15,000.

Like other local dealers in the field, Chen travels monthly to China to pick up items like chairs, tables, cabinets, stools and boxes, as well as larger items such as canopy beds, screens, wooden windows and door carvings.

Chen says the softwood furniture has dropped in price by about 10 percent and is popular among younger, middle-class customers.

Aiming for the higher end of the market is Jeff Hsu's Oriental Art (觀想文物藝術), which manager Jessica Hsu (徐盼蘋) says has been hit by a more sluggish economy. Nonetheless, the store carries almost exclusively Zitan and Huanghuali items, which usually cost more than NT$1 million apiece.

"I don't really advertise," says Hsu of her limited clients. "My customer list is quite selective. Whenever I have new pieces coming in, I phone a couple of people, and I also mail the information to a few museums and foundations overseas."

Despite high prices, some private and public collectors still purchase quality antiques.

The preferred Ming furniture is simple and fluid in design, while Ching furniture features extravagant designs with intricate carving and other accessories like inlays of stones and gold.

Each type of furniture also has several distinct styles. For example, there are several types of chairs, such as the chuanyi (圈椅), a chair with a crest-shaped back, or, an official's hat chair, which has a tall yoke back and lower armrests, or a lady's chair, which usually does not have armrests and has carvings of flowers or women. Different types of tables include waist tables (束腰桌), which feature an indented edge and Kang tables (炕桌), which are low rectangular tables normally no higher than 65cm used on the brick beds common in northern China.

Other stores in Taipei have followed Chen's footsteps, adjusting their stock from Zitan and Huanghuali pieces to more affordable softwood pieces, though few can report growing sales.

"Between 1992 and 1995, I was selling dozens of items per month," owner of Artasia (亞細亞佳) John Ang (洪光明) recalls of the consumer frenzy 10 years ago. Expensive hardwood pieces currently may wait in his shop for a month before being bought.

Ang added that hardwood pieces have become difficult to source, another reason for diversifying into cheaper softwood products. He now sells elm pieces from Shanxi Province (山西) and items made of fine grained southern elm called Ju wood (櫸木) from Jiangsu Province (江蘇). Ang also purchases furniture in Guangdong (廣東) and Shandong (山東) Provinces.

The stock at Ang's store is more tailored to average consumers looking for home decoration than to dedicated collectors. Ang sells official's hat chairs for about NT$12,000 or matching softwood chairs for about twice that price, depending on their design and age.

"The simplicity of Ming style, with clean lines and curves and with little elaboration is still the favorite, because it goes well with modern settings," Ang said, adding that customers are now combining classical and modern furniture, instead of spending on a whole classical living room or bedroom setup.

Ko Chin-han's (柯宸瀚) stock at Dragon Antique Gallery (天祥古董家俱) covers an even wider selection with average people's daily-use items such as children's bathtubs, rice buckets and lamp stands. Some designs are ingenious, like a stool that can be turned into a ladder and a laundry bucket. An antique dealer for 10 years, Ko travels to China three times a year to buy new pieces, looking mostly in the coastal provinces of Fujian (福建) and Zhejiang (

Dragon Antique also includes some high-end items, such as a Guifei chair (貴妃椅), a spacious two-seat chair for ladies with a small table in the middle, that runs about NT$90,000, and a neo-Baroque lady's chair from Shanghai, priced at about NT$30,000.

There is no concrete pricing system for antiques and authenticity is often difficult to determine, so without being an expert in the field, consumers are forced to trust the dealer's credibility and settle for a measure of uncertainty and their emotional attachment to the items they choose.

Sabrina Revel, a 28-year-old French Taipei resident, was thankful for the drop in antique prices. After hunting through several stores, she finally found a late 19th century altar table of walnut wood at an affordable price of NT$70,000. "I have heard of how expensive Chinese antique furniture can be, and I am glad it's getting affordable, because this is as much as I can offer."

July 28 to Aug. 3 Former president Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石) reportedly maintained a simple diet and preferred to drink warm water — but one indulgence he enjoyed was a banned drink: Coca-Cola. Although a Coca-Cola plant was built in Taiwan in 1957, It was only allowed to sell to the US military and other American agencies. However, Chiang’s aides recall procuring the soft drink at US military exchange stores, and there’s also records of the Presidential Office ordering in bulk from Hong Kong. By the 1960s, it wasn’t difficult for those with means or connections to obtain Coca-Cola from the

No one saw it coming. Everyone — including the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) — expected at least some of the recall campaigns against 24 of its lawmakers and Hsinchu Mayor Ann Kao (高虹安) to succeed. Underground gamblers reportedly expected between five and eight lawmakers to lose their jobs. All of this analysis made sense, but contained a fatal flaw. The record of the recall campaigns, the collapse of the KMT-led recalls, and polling data all pointed to enthusiastic high turnout in support of the recall campaigns, and that those against the recalls were unenthusiastic and far less likely to vote. That

A couple of weeks ago the parties aligned with the People’s Republic of China (PRC), the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP), voted in the legislature to eliminate the subsidy that enables Taiwan Power Co (Taipower) to keep up with its burgeoning debt, and instead pay for universal cash handouts worth NT$10,000. The subsidy would have been NT$100 billion, while the cash handout had a budget of NT$235 billion. The bill mandates that the cash payments must be completed by Oct. 31 of this year. The changes were part of the overall NT$545 billion budget approved

Trolleys piled high with decapitated silicon monster heads, tattooed dealers lurking in alleyways, bin bags of contraband hidden behind shop counters: welcome to the world of Lafufus. Fake Labubus (拉布布), also known as Lafufus, are flooding the hidden market. As demand for the collectable furry keyrings soars, entrepreneurs in the southern trading hub of Shenzhen are wasting no time sourcing imitation versions to sell to eager Labubu hunters. But the Chinese authorities, keen to protect a rare soft-power success story, are cracking down on the counterfeits. “Labubus have become very sensitive,” says one unofficial vendor, in her small, unmarked, fake designer goods