When Victor Chen (陳國雄) was growing up in Changhwa, he could buy all the pirated music he wanted for little more than the cost of the cassette tape it came on. At the same time, his father was a legitimate music distributor in Taiwan's counterfeit infested retail markets.

As businesses go, Taiwan's early music industry was a murky swamp of quasi-legalities. Maybe that's where Chen got such screwy notions of how to sell music by giving it away. Maybe it's what led him to MP3.

Last week, Chen and his brother Chen Kuo-hwa (陳國華) launched Kuro.com.tw, the world's first Chinese service for the free exchange of music over the Internet. It follows the basic blueprint of the now infamous Napster Web site, which uses central servers to link users and help them copy each other's music. Songs are compressed according to the digital MP3 file format, which allows for easy transmission over the Web. All you have to do is register and download a small software package, then you can effectively copy songs for free. Last year, home users around the world did this in excess of one billion times.

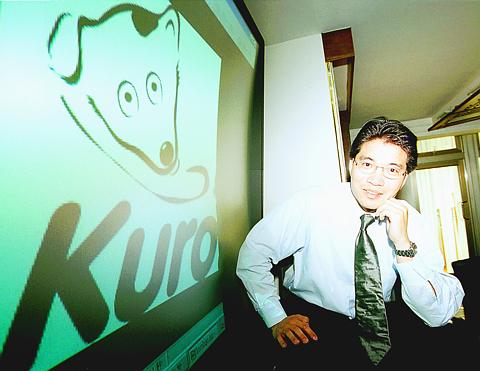

PHOTO: CHIANG YING-YING, TAIPEI TIMES

All told, Kuro makes only a few modifications to the Napster plan. First and foremost, Kuro is Chinese compatible, allowing users to search for songs and artists using their Chinese names. That makes it easy to find mando-pop idols like Coco Lee (李玟) and Wang Lee-hom (王力宏), who don't turn up many hits on Napster, or if they do, the song titles tend to be garbled. In its first week, despite a few bugs still in the software, Kuro.com.tw logged on more than 12,000 users.

Language and glitches aside, however, Kuro also offers a fresh perspective on the ideological and legal debates surrounding MP3. In recent months, the controversy has jarred America's music industry to its very foundations. Big record companies and megabuck rock bands, such as Metallica and Dr. Dre, feel that they are being ripped off by online music sharing, so they are suing Napster and other companies for copyright infringement. Meanwhile, other artists, represented most vociferously by Courtney Love and Public Enemy front man Chuck D, and many consumers, like those who sent more than 100,000 emails to the US Senate Judiciary Hearing on the "Future of Digital Music," have shown overwhelming support for the MP3 movement.

But Kuro, somehow, is trying to sidestep most of these ugly politics. The Chens think they may be able to get away with it because they are doing something that Napster has never done. They are selling CDs and other digital music, both over the Internet and in stores.

ILLUSTRATION: SWEET WATERMELON & CONSTANCE CHOU

Which raises an intriguing question: are they just plain loony to charge money for music and give it away at the same time? Victor Chen says no.

He believes that at present, four main channels exist for music distribution: retail sales, paid digital downloads, free Internet-based music swapping and piracy. His company engages in the first three of these methods. It sells CDs and pay-per-song downloads from the site Music.com.tw and lets users share their MP3s through Kuro.com.tw.

As for MP3s, Chen sees them as a promotional tool that can only enlarge the overall market. "The speed of growth of the CD market is according to a limited curve," he said, pointing out that his company's major source of revenue is online shopping, which accounted for NT$30 million in income during the first half of this year. His other revenue channels include digital downloads and advertising. Thus, he's using MP3 as only one piece in his marketing puzzle. "Our goal is to establish a community," he said.

But will the local music industry forgive Chen just because he's got a holistic approach? It's not likely, but Chen's not that stupid either. "We've talked to our lawyer, who told us that what we're doing does not violate Taiwan's copyright laws," said Maggie Ko, Kuro's business development director, who also expected that record labels such as Sony Music, Universal, EMI, Warner, and BMG would have other lawyers with differing opinions.

Her prediction was not hard to corroborate. "Sony's worldwide policy is not to allow free downloads of its music," said Belinda Ho of Sony Music Taiwan's publishing and royalties department, who was not aware of what Kuro was doing. "If we determine that this [file sharing through Kuro] is illegal, we will take action."

Such rhetoric likely portends the spread of the MP3 debate to Taiwan. Already, things are shaping up as they have in the US, with the big guys (record companies) versus the little guys (consumers and artists).

"We already have a song on Kuro that came off of a compilation," said Lin You-tze (林佑子), drummer for a Taipei underground band called the Sugar Plum Fairy (甜梅號), which will put out between 500 and 1,000 copies of its first CD later this year. "We don't have any problem with it. We don't care about the money. We just care about the music and want more people to listen."

On the other side of the fence, mainstream heartthrob Sony recording artist Wang Lee-hom has echoed the opinions of his label, likening MP3 music sharing to "shoplifting."

None of this surprises Victor Chen. "There's no way we're going to help the ten biggest artists, but we will help the other nine-hundred and ninety out of a thousand. The people who are scared are the major labels," he said, adding, "when the tape recorder came out, they were worried about that, too."

Following the shock complete failure of all the recall votes against Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) lawmakers on July 26, pan-blue supporters and the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) were giddy with victory. A notable exception was KMT Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫), who knew better. At a press conference on July 29, he bowed deeply in gratitude to the voters and said the recalls were “not about which party won or lost, but were a great victory for the Taiwanese voters.” The entire recall process was a disaster for both the KMT and the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP). The only bright spot for

Water management is one of the most powerful forces shaping modern Taiwan’s landscapes and politics. Many of Taiwan’s township and county boundaries are defined by watersheds. The current course of the mighty Jhuoshuei River (濁水溪) was largely established by Japanese embankment building during the 1918-1923 period. Taoyuan is dotted with ponds constructed by settlers from China during the Qing period. Countless local civic actions have been driven by opposition to water projects. Last week something like 2,600mm of rain fell on southern Taiwan in seven days, peaking at over 2,800mm in Duona (多納) in Kaohsiung’s Maolin District (茂林), according to

Aug. 11 to Aug. 17 Those who never heard of architect Hsiu Tse-lan (修澤蘭) must have seen her work — on the reverse of the NT$100 bill is the Yangmingshan Zhongshan Hall (陽明山中山樓). Then-president Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石) reportedly hand-picked her for the job and gave her just 13 months to complete it in time for the centennial of Republic of China founder Sun Yat-sen’s birth on Nov. 12, 1966. Another landmark project is Garden City (花園新城) in New Taipei City’s Sindian District (新店) — Taiwan’s first mountainside planned community, which Hsiu initiated in 1968. She was involved in every stage, from selecting

As last month dawned, the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) was in a good position. The recall campaigns had strong momentum, polling showed many Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) lawmakers at risk of recall and even the KMT was bracing for losing seats while facing a tsunami of voter fraud investigations. Polling pointed to some of the recalls being a lock for victory. Though in most districts the majority was against recalling their lawmaker, among voters “definitely” planning to vote, there were double-digit margins in favor of recall in at least five districts, with three districts near or above 20 percent in