It was freezing near the top of the mountain, but that was the least of our troubles. A razor wind that had moments ago been ripping strands of mist over the jagged, slate peaks ahead of us had now brought with it a cloud bank so thick it was hard to see the trail a few meters ahead.

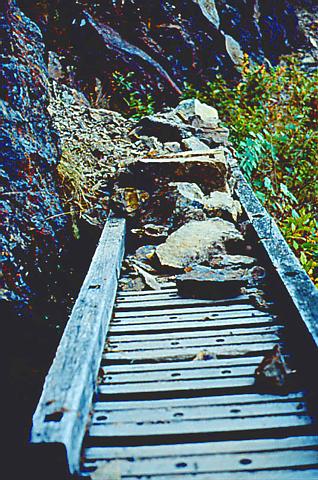

And then there was the earthquake damage: huge gaps in the trail gouged out by rockslides; loose scree and lone, restless boulders just waiting to be set in motion by the slightest tap or vibration.

It was this combination of factors that prompted our climbing guide, Yushan National Park Ranger Richard Chen, to take shelter from the wind in a rock crevice 300-meters from the summit of Yushan (Jade Mountain).

PHOTO: JAY SPEIDEN, TAIPEI TIMES

"It's too windy," he yelled. "If this doesn't break, we might have to turn back."

These were not the words we wanted to hear after a day and a half of climbing, especially considering that Taiwan's tallest summit now loomed tantalizingly close, just a scramble away. But because we were among the first climbers to try for the summit since the 921 earthquake, loose rocks and downed guide-chains meant it could be a dangerous scramble. So we sheltered behind a ledge and waited -- hoping that the weather would break before the bitter cold and late hour forced us to turn back.

An invitation to danger

PHOTO: JAY SPEIDEN, TAIPEI TIMES

Yushan is northeast Asia's tallest peak. Standing at 3,952 meters -- roughly 13,000 feet -- it is a broad-shouldered hulk of a mountain, the centerpiece of Yushan National Park, a rugged, mountainous region in central Taiwan dotted with more than 30 peaks higher than 3,000 meters.

By far the most pristine of Taiwan's parks, Yushan National Park is a national treasure. Relatively untouched, the park is one of the few conservation success stories in Taiwan's history. It also was almost at the epicenter of the devastating 921 earthquake.

I had been in touch with the park service on several occasions about doing a story on the state of the national park in the wake of the earthquake. But my pleas to be taken into the still-closed park had been fruitless. It wasn't until a day before the actual climb that the phone rang. It was Chen.

PHOTO: JAY SPEIDEN, TAIPEI TIMES

"Can you be at the ranger station in Shuili by tomorrow morning?" he asked. "I'm taking a guy to the top who wants to film a documentary about the damage the quake caused to the trail systems," Chen said. "If you can make it you're welcome to come along."

It wasn't until Chen got to the part about release forms that I started to realize that this might actually be dangerous. "You'll also need to bring a signed release form that frees the park from responsibility if anything ... bad should happen," Chen said.

"Bad?"

PHOTO: JAY SPEIDEN, TAIPEI TIMES

"Well, we have reports that the trail is in bad shape from the earthquake and there are some dangerous places," he explained. "Also, there is still the possibility of aftershocks. We'll provide hardhats, but there could be falling rocks."

After setting plans to meet Chen in Shuili, I rang Dr Chiu Hung-chie, a seismologist at Academia Sinica, to try to get a better picture of what I'd gotten myself into. The first thing I learned is that we would probably be climbing higher, by several meters, than we would have had we tried to climb Yushan Mountain before the earthquake.

"Yes, the mountain is taller now," Chiu explained. "The 921 earthquake was unique because it struck close to the earth's crust, causing major topical and geological changes."

PHOTO: JAY SPEIDEN, TAIPEI TIMES

Chiu explained that Taiwan is divided into two halves known to seismologists as the "hanging wall," or east side, and the "foot wall," or west side. Both walls are influenced by two opposing systems, the Philippine Plate and the Eurasian Plate, that are being pressed together at a rate of about 7cm per year. "Basically, pressure released during the 921 quake caused the hanging wall to break and spring upward by several meters. Jade Mountain is on the hanging wall, so, of course, it jumped upwards as well."

As I hurried off to collect and pack my gear I had to wonder about the type of force that can toss a 13,000 ft slate and meta-sandstone mountain, the largest in northeast Asia, several meters upwards in a matter of seconds. I also had to wonder what other kinds of collateral damage is caused when millions of tons of brittle rock are instantly "sprung" into the air.

I hoped Chen did not forget the hardhats.

PHOTO: JAY SPEIDEN, TAIPEI TIMES

The broken trail

I met Chen and a man named Mr Hsu at the ranger station in Shuili. Mr Hsu, a teacher and avid mountain climber, would be documenting the trip on video to show his students. The last thing we did before heading for the mountain was stop at an office building and buy three-day accident insurance policies for NT$300.

The twisting ride up into Yushan National Park, a white-knuckled trip on the best of days, was made worse by the constant sight of giant boulders, each equal to or larger than our minivan, that had recently been cleared to the side of the road.

PHOTO: JAY SPEIDEN, TAIPEI TIMES

We arrived at the mountain hostel after dark, ate a quick meal and retired for the night to a large Japanese-style tatami room. I then proceeded to toss and turn all night until Mr Hsu sprung up at 5am sharp and screamed "Let's get going!"

The 10-foot granite gateway to the trail was twisted in the ground and tilting sharply to the left, a greeting and a reminder that, this time, the trail might have a few surprises.

About a half kilometer up we came across our first rockslide

of the day. It had wiped out not only the trail, but the trees and undergrowth as well. What was left was an unstable layer of soft, churned earth scattered over with flakes of loose shale. As each climber scrambled over the washout, we heard first the click of tiny pebbles becoming loosened, and then small rockslides further down the hill.

In a few spots, giant boulders sat alone in the middle of the trail. You could see where they had crashed down the hill, gouging a wide swath in the earth while cutting down bamboo and, sometimes, full-grown trees. Mr Hsu filmed them while I considered the folly of wearing a hardhat as protection against the equivalent of a VW Beetle hurtling downwards from thousands of feet above.

The higher we got, the colder and wetter the weather became. Chen, a methodical hiker, stopped often not only to inspect trail damage, but brightly colored lichen beds, birds, stands of hemlock trees and a variety of butterflies. "Yushan is one of the only areas in Taiwan that can support three distinct climates and ecosystems," Chen mused as he hiked.

At around 5pm we made it to the base camp hostel, exhausted from the 10-km hike. We cooked some noodles and fell into our sleeping bags. Unlike the night before, I slept hard until Mr Hsu roused us again at 4am to head for the summit. We set off through the freezing darkness with moonlight as our only guide.

Faultline in the sky

An hour later, backlit by the light of dawn, Yushan's summit came into view. Out over the valley, large, ragged blankets of mist were sweeping our way. Still, Chen set an unhurried pace and we moved slowly across the random rockslides and around the downed boulders that appeared along the trail every hundred meters or so.

"The mountain moved," Chen explained as we stopped to munch chocolate and drink water. "That's why there is so much displacement of rock. But, still, we haven't had a good rain since the quake and I suspect that once we do and erosion sets in, the damage will get worse. Only after that will nature start to repair itself."

At the base of the summit we began the only part of the climb that can be considered even remotely technical. The clouds started building as we scrambled over rocks heading for the "Gate," a steel-and-net structure designed to take climbers along a windswept ridge to the summit without the risk of being blown off the mountain -- which has actually happened.

A large part of the Gate had been torn down by the quake and lay in a twisted heap halfway down a boulder-strewn slope. It was here that the wind kicked up and Chen pulled us into the crevice to take shelter. After about forty minutes, the wind died suddenly. We stood, shook the frost off our hands and feet and scrambled to the top.

By the time we reached the summit the wind had died, but the clouds were still thick, obscuring our view. A giant fissure had opened in the rock, bisecting the entire summit. We posed for photographs, our legs splayed over the fault -- one foot planted on the "hanging wall," one on the "foot wall." After two days of climbing, we'd gone as high as Taiwan would allow us, but still not beyond the reach of the earthquake that shook the island from bottom to very top.

In the next few months tough decisions will need to be made by the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) and their pan-blue allies in the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). It will reveal just how real their alliance is with actual power at stake. Party founder Ko Wen-je (柯文哲) faced these tough questions, which we explored in part one of this series, “Ko Wen-je, the KMT’s prickly ally,” (Aug. 16, page 12). Ko was open to cooperation, but on his terms. He openly fretted about being “swallowed up” by the KMT, and was keenly aware of the experience of the People’s First Party

Aug. 25 to Aug. 31 Although Mr. Lin (林) had been married to his Japanese wife for a decade, their union was never legally recognized — and even their daughter was officially deemed illegitimate. During the first half of Japanese rule in Taiwan, only marriages between Japanese men and Taiwanese women were valid, unless the Taiwanese husband formally joined a Japanese household. In 1920, Lin took his frustrations directly to the Ministry of Home Affairs: “Since Japan took possession of Taiwan, we have obeyed the government’s directives and committed ourselves to breaking old Qing-era customs. Yet ... our marriages remain unrecognized,

Not long into Mistress Dispeller, a quietly jaw-dropping new documentary from director Elizabeth Lo, the film’s eponymous character lays out her thesis for ridding marriages of troublesome extra lovers. “When someone becomes a mistress,” she says, “it’s because they feel they don’t deserve complete love. She’s the one who needs our help the most.” Wang Zhenxi, a mistress dispeller based in north-central China’s Henan province, is one of a growing number of self-styled professionals who earn a living by intervening in people’s marriages — to “dispel” them of intruders. “I was looking for a love story set in China,” says Lo,

During the Metal Ages, prior to the arrival of the Dutch and Chinese, a great shift took place in indigenous material culture. Glass and agate beads, introduced after 400BC, completely replaced Taiwanese nephrite (jade) as the ornamental materials of choice, anthropologist Liu Jiun-Yu (劉俊昱) of the University of Washington wrote in a 2023 article. He added of the island’s modern indigenous peoples: “They are the descendants of prehistoric Formosans but have no nephrite-using cultures.” Moderns squint at that dynamic era of trade and cultural change through the mutually supporting lenses of later settler-colonialism and imperial power, which treated the indigenous as