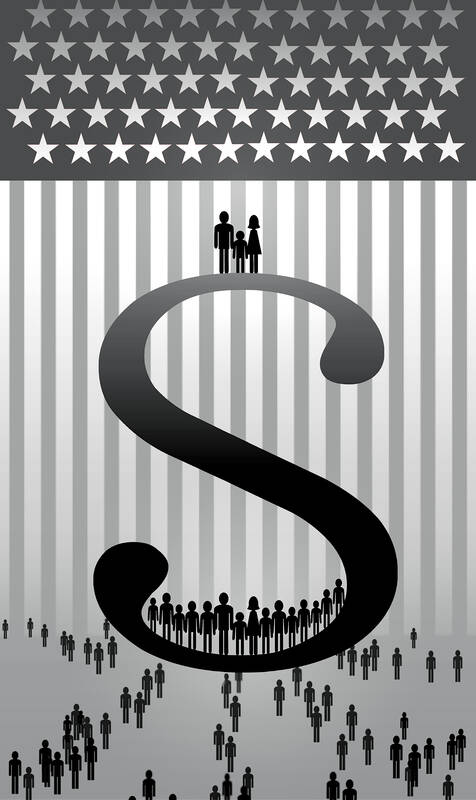

The good news is that Americans have never been richer. The bad news is that most of them do not feel like it.

There has been tremendous growth in income and wealth in the US in the last half century, even for poorer and middle-class households. However, because of the nature of that growth, as well as the changing structure of the national economy, a lot of the people who have benefited believe that the economy is not working for them.

It is true the middle class is shrinking. In the 1960s the income distribution of US households looked like a bell curve with a very thick middle. Today there are fewer Americans in the middle — largely because many have joined the ranks of the upper-middle class. In 1967, a little more than 5 percent of Americans earned or received more than US$150,000 (in 2024 dollars). Now more than 30 percent do. And it is not just the middle class that moved up: In 1967, more than 38 percent earned or received less than US$50,000. Now that figure is 21 percent.

Illustration: Yusha

Income inequality increased. The very rich — the top 5 percent and especially the top 1 percent — got much richer than everyone else, even the top 20 percent. The income distribution curve has flattened as more people have moved into the upper part, with the upper tail moving even further from everyone else.

The result? More Americans than ever are affluent — and more have the sense that something is wrong with the economy.

Americans earned more for several reasons. The first is that neoliberal economic policies worked as intended. In the last 50 years, there have been big increases in productivity, solid GDP growth and, since the 1980s, low and predictable inflation. All this helped make most Americans richer.

There has been a decline in unionization, which helped to compress wages between the upper tail of the income distribution and the middle. More Americans go to college, where they incur debt but increase their lifetime earnings, especially as technology favors people with degrees. Americans are older, and people tend to earn more later in their careers. On the lower end, income grew in part because the figure includes welfare benefits and tax credits.

There are legitimate reasons that many households feel poorer, even if their income is greater. It is a struggle to keep up with the price increases of many critical services in regulated sectors such as health care, education and housing. There is some justified anxiety that the earnings growth and prosperity will not continue. The last 60 years was the Era of the Baby Boomers, when income gains were large for anyone who went to college. The college premium still exists, but it has stopped growing and it comes at a higher cost.

And while technology and trade have made everyone richer, they have made a far smaller group of people much, much richer. It is not just the handful of people who are rich beyond comprehension. There are hundreds of Americans who are worth more than a billion dollars. This is in part because technology changed and a few firms earned more — and paid more — than the rest. Working in certain industries means much higher earnings. And a superstar economy rewards high performers much more than everyone else, whether that superstar is Taylor Swift or a talented manager in a fast-growing corporation.

To be clear, this system helps create economic growth that makes everyone better off. However, in the very top tier of income, it can feel like a zero-sum competition between the merely affluent and the truly rich.

This poses a challenge not just for economic planners but for the very meaning of prosperity. Growth and rising incomes are usually the goal of economic policy, including neoliberal economic policy. However, the last two decades show that rising incomes are not always enough to engender good feelings about the economy.

This intra-top-quartile resentment might help explain why more politicians want higher taxes on super-high earners but do not ask the upper middle class to pay any more. The taxes are not just a way to pay for more middle-class welfare benefits. They are a form of economic retribution.

The catch is that there is a tradeoff between growth and equality. At least some of the growth at the top came from more productivity. Innovative companies, some founded or led by billionaires, help make the American economy (or at least Americans’ stock portfolios) richer. Yes, there is room to increase taxes on the rich, but punitive taxes can harm growth.

The idea that the economy is rigged and zero-sum is leading to a rise in populism in both parties. The result would probably be less trade and more price controls, which would mean a slower-growing economy — or even one that is shrinking. Then Americans would learn that the only thing worse than rising inequality is flat or declining income.

Allison Schrager is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering economics. A senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute, she is author of “An Economist Walks Into a Brothel: And Other Unexpected Places to Understand Risk.” This column reflects the personal views of the author and does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

China badly misread Japan. It sought to intimidate Tokyo into silence on Taiwan. Instead, it has achieved the opposite by hardening Japanese resolve. By trying to bludgeon a major power like Japan into accepting its “red lines” — above all on Taiwan — China laid bare the raw coercive logic of compellence now driving its foreign policy toward Asian states. From the Taiwan Strait and the East and South China Seas to the Himalayan frontier, Beijing has increasingly relied on economic warfare, diplomatic intimidation and military pressure to bend neighbors to its will. Confident in its growing power, China appeared to believe

After more than three weeks since the Honduran elections took place, its National Electoral Council finally certified the new president of Honduras. During the campaign, the two leading contenders, Nasry Asfura and Salvador Nasralla, who according to the council were separated by 27,026 votes in the final tally, promised to restore diplomatic ties with Taiwan if elected. Nasralla refused to accept the result and said that he would challenge all the irregularities in court. However, with formal recognition from the US and rapid acknowledgment from key regional governments, including Argentina and Panama, a reversal of the results appears institutionally and politically

In 2009, Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC) made a welcome move to offer in-house contracts to all outsourced employees. It was a step forward for labor relations and the enterprise facing long-standing issues around outsourcing. TSMC founder Morris Chang (張忠謀) once said: “Anything that goes against basic values and principles must be reformed regardless of the cost — on this, there can be no compromise.” The quote is a testament to a core belief of the company’s culture: Injustices must be faced head-on and set right. If TSMC can be clear on its convictions, then should the Ministry of Education

The Chinese People’s Liberation Army (PLA) provided several reasons for military drills it conducted in five zones around Taiwan on Monday and yesterday. The first was as a warning to “Taiwanese independence forces” to cease and desist. This is a consistent line from the Chinese authorities. The second was that the drills were aimed at “deterrence” of outside military intervention. Monday’s announcement of the drills was the first time that Beijing has publicly used the second reason for conducting such drills. The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) leadership is clearly rattled by “external forces” apparently consolidating around an intention to intervene. The targets of