Hong Kong is quickly becoming a college town. The number of non-local students, mostly from China, has nearly doubled since 2021, with the surge primarily driven by a sharp increase in postgraduate studies.

The young population inflow has given a boost to a gloomy economy that has been suffering from a prolonged property downturn. Residential rents are flirting with record highs, while cash-rich universities are buying up real estate across the city to use for classroom and dormitory housing.

For many, it is a significant financial commitment. Hong Kong is an expensive city to live in, and universities have been raising tuition. Hong Kong University (HKU), for instance, is charging non-STEM students about HK$198,000 (US$25,479), a 9 percent increase from a year ago.

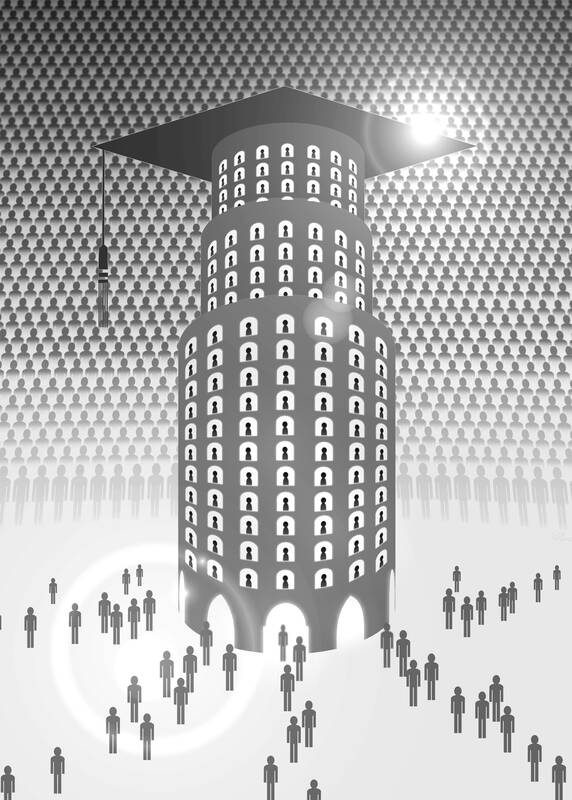

Illustration: Yusha

Why are Chinese students suddenly so enamored with the city’s universities, even though there are many good ones in the mainland? In the last academic year, more than 70 percent of non-local students are from mainland China.

China has always prized its top 1 percent, lavishing millions of dollars on high-profile researchers while brushing aside younger ones who work in smaller laboratories. This inequality has become more pronounced in the past few years, even as the overall pie has grown. What should an ambitious 18-year-old, who wants to do cutting-edge research, do if she cannot make it to Beijing’s prestigious Tsinghua University, the world’s top institution for computer science?

Top universities in Hong Kong offer a good compromise. A less-than-ideal performance in the gaokao (高考), or the national entrance exam, could cost an aspiring scholar a spot at Tsinghua. However, the gaokao score is not the only thing for admissions to top programs in the financial hub, where resources are more evenly distributed among students.

As China’s economy undergoes a structural transition, families are starting to realize that majors matter as much as a university’s brand name. In just five years, finance and civil engineering are out, while nursing and mechanical engineering are in. How then do college students hedge the macro risk that their specialties become obsolete as soon as they graduate?

Students in Hong Kong do not have to declare their specializations until much later, and more than half graduate with multiple majors, according to Allen Huang, former associate dean of Hong Kong University of Science and Technology’s (HKUST) business school, who now chairs the accounting department.

It is even possible for a business student to switch to engineering, although she might need to spend an extra year to fulfil different foundational curriculum requirements.

Of course, some also prefer to be a big fish in a small pond, running away from the race-to-bottom mentality prevalent in the mainland. Last year, more than 20 percent of Hong Kong high-schoolers got into top-tier universities, such as HKU, HKUST and City University of Hong Kong. By comparison, the admissions rate at China’s elite Project 985 universities is in the low single digits. As such, when a Chinese student comes to Hong Kong, they can expect to be top of the class, paving the way for well-paying jobs in the future.

Hong Kong also offers much higher pay. In the mainland, a Tsinghua graduate with three years of work experience makes 238,188 yuan (US$33,526) on average, according to Zhaopin Ltd, an online recruiting services platform. If they enroll at HKUST instead, they can expect to make roughly 80 percent more, at HK$480,000 a year, according to data compiled by the university. A top graduate could make as much as HK$1 million.

People often think of Hong Kong as a global financial center, but the city is a lot more than just a funding platform for Chinese companies that want to expand overseas or an asset management hub that caters to mainland’s wealthy. For decades, it has been a refuge — and a steppingstone — for millions who want an escape from rigid cultural and political norms in the north.

It turns out, higher education is Hong Kong’s other strong suit.

Shuli Ren is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering Asian markets. A former investment banker, she was a markets reporter for Barron’s. She is a CFA charterholder. This column reflects the personal views of the author and does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

After more than three weeks since the Honduran elections took place, its National Electoral Council finally certified the new president of Honduras. During the campaign, the two leading contenders, Nasry Asfura and Salvador Nasralla, who according to the council were separated by 27,026 votes in the final tally, promised to restore diplomatic ties with Taiwan if elected. Nasralla refused to accept the result and said that he would challenge all the irregularities in court. However, with formal recognition from the US and rapid acknowledgment from key regional governments, including Argentina and Panama, a reversal of the results appears institutionally and politically

In 2009, Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC) made a welcome move to offer in-house contracts to all outsourced employees. It was a step forward for labor relations and the enterprise facing long-standing issues around outsourcing. TSMC founder Morris Chang (張忠謀) once said: “Anything that goes against basic values and principles must be reformed regardless of the cost — on this, there can be no compromise.” The quote is a testament to a core belief of the company’s culture: Injustices must be faced head-on and set right. If TSMC can be clear on its convictions, then should the Ministry of Education

The Chinese People’s Liberation Army (PLA) provided several reasons for military drills it conducted in five zones around Taiwan on Monday and yesterday. The first was as a warning to “Taiwanese independence forces” to cease and desist. This is a consistent line from the Chinese authorities. The second was that the drills were aimed at “deterrence” of outside military intervention. Monday’s announcement of the drills was the first time that Beijing has publicly used the second reason for conducting such drills. The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) leadership is clearly rattled by “external forces” apparently consolidating around an intention to intervene. The targets of

China’s recent aggressive military posture around Taiwan simply reflects the truth that China is a millennium behind, as Kobe City Councilor Norihiro Uehata has commented. While democratic countries work for peace, prosperity and progress, authoritarian countries such as Russia and China only care about territorial expansion, superpower status and world dominance, while their people suffer. Two millennia ago, the ancient Chinese philosopher Mencius (孟子) would have advised Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平) that “people are the most important, state is lesser, and the ruler is the least important.” In fact, the reverse order is causing the great depression in China right now,