It is every baby’s first food, and we cannot get enough of it. The world produces close to one billion metric tons of milk each year — more than all the wheat or rice we grow. That lead is set to widen over the coming decade, with dairy consumption expected to grow faster than any other agricultural commodity. On a rapidly warming planet, this poses a host of problems.

Consider demand. There are more than half a billion people younger than four in developing countries, with about one-third of them affected by stunting — a condition that is associated with health, educational and economic problems in later life. Most could benefit from the policy first proposed by Scottish nutritionist John Boyd Orr in the 1920s: provision of dairy products to give them a more nutritionally rich diet.

That is one of the main pillars of Indonesian President Prabowo Subianto’s newly introduced free-school meals program.

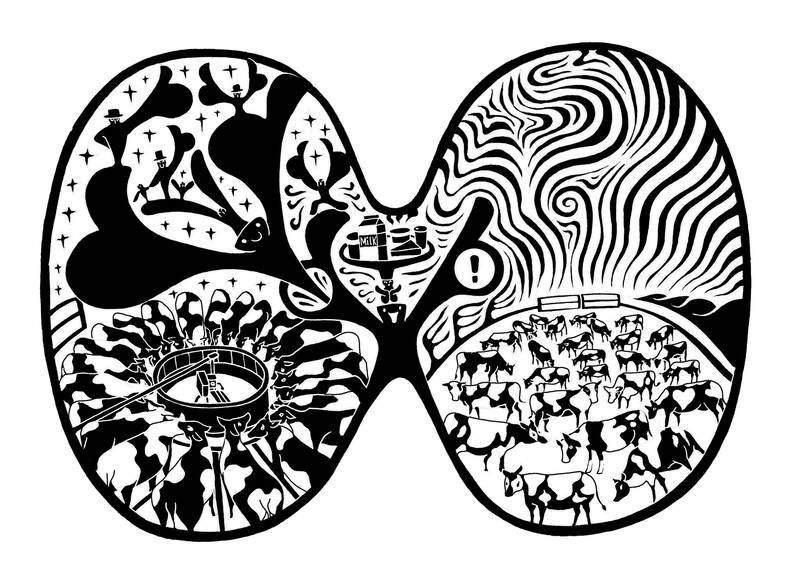

Illustration: Mountain People

In terms of human welfare, we should be welcoming this trend. Dairy products are relatively expensive, and we consume more of them as we rise above the most basic subsistence levels.

If South Asia, Southeast Asia and sub-Saharan Africa are likely to see booming consumption over the coming decade, as the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development forecast last week, it is largely a positive symptom of their long-awaited economic development.

The problem comes when you start looking at supply. Milk is mostly being produced in the wrong places for the young stomachs that need it.

More than 90 percent of children younger than four are in developing countries — but the same nations produce barely half of the world’s milk.

Europe alone represents one-quarter of global output, and highly perishable dairy products are not much sold across borders. For instance, the total worldwide trade in whole milk powder — after a decade when China’s hunger for baby formula upended the global dairy industry — accounts for about 2 percent of raw milk. Even that limited commerce has been sufficient to upset local supply chains. In New Zealand, often likened to the Saudi Arabia of dairy due to its dominance in exports, demand from Southeast Asian importers drove whole milk powder prices to a three-year high in May, while butter inflation is running above 50 percent.

With trade providing only limited relief, we are most likely to see shortages, as rising demand from developing countries is met with limited increases in supply.

The world’s milk deficit would hit 30 million tons by 2030, the International Dairy Federation said in April. The IFCN Dairy Research Network, a separate group, still sees a 10.5 million ton shortfall by the same date. That dairy drought would push prices beyond the reach of those who most need it.

Climate change makes all of this worse. Rising temperatures would mean it is even harder for tropical and subtropical countries to be self-sufficient: Extreme heat can cut milk production by as much as 10 percent, according to a study in the journal Science Advances earlier this month.

Milk is also a major culprit in global warming, as well as a victim of it. Dairy cattle emissions, mostly from methane-dense burps as cows digest grass, amount to 2.1 billion tons of carbon dioxide a year, equivalent to what’s caused by two-thirds of all cars. The shift to more production in developing nations will make this even worse.

Pollution for each kilogram of raw milk in Africa and South Asia is three to four times higher than in developed countries, because the mechanized, intensive dairy farming practiced in the rich world has a far lower carbon footprint.

What can be done to fix this? Wealthy nations whose appetite for plant-based alternatives appears to be wavering should recommit to their shift away from livestock-based food.

Far too much of our limited capacity to sustain dairy production is still being hogged by affluent populations who have grown so jaded that we now use milk for luxuries like body-building supplements, as much as for basic nutrition.

Relatively prosperous developing countries such as China and Brazil can also up their game by moving to more intensive farming. They could get by with one-third of their current dairy herd if they raised yields to developed-world levels.

In India, the biggest dairy producer, the benefits could be even greater. Thanks to religious objections to the slaughter of cows after they stop producing, there are more than five million stray cattle roaming the streets, spreading disease, attacking people, getting hit by traffic and fueling organized crime.

A smaller, more intensively raised herd would shrink this bovine epidemic. Greater dairying of buffalo, which already accounts for about half of India’s milk and is not considered sacred, would also help.

However, one thing is certain: Exhorting poor countries to give up the nutritional benefits of dairy that their richer peers have benefited from is repugnant, and bound to fail.

If we want to reduce milk’s carbon footprint, we are going to need to produce it more efficiently, rather than hoping the problem will just go away.

David Fickling is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering climate change and energy. Previously, he worked for Bloomberg News, the Wall Street Journal and the Financial Times.

A failure by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) to respond to Israel’s brilliant 12-day (June 12-23) bombing and special operations war against Iran, topped by US President Donald Trump’s ordering the June 21 bombing of Iranian deep underground nuclear weapons fuel processing sites, has been noted by some as demonstrating a profound lack of resolve, even “impotence,” by China. However, this would be a dangerous underestimation of CCP ambitions and its broader and more profound military response to the Trump Administration — a challenge that includes an acceleration of its strategies to assist nuclear proxy states, and developing a wide array

Eating at a breakfast shop the other day, I turned to an old man sitting at the table next to mine. “Hey, did you hear that the Legislative Yuan passed a bill to give everyone NT$10,000 [US$340]?” I said, pointing to a newspaper headline. The old man cursed, then said: “Yeah, the Chinese Nationalist Party [KMT] canceled the NT$100 billion subsidy for Taiwan Power Co and announced they would give everyone NT$10,000 instead. “Nice. Now they are saying that if electricity prices go up, we can just use that cash to pay for it,” he said. “I have no time for drivel like

Twenty-four Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) lawmakers are facing recall votes on Saturday, prompting nearly all KMT officials and lawmakers to rally their supporters over the past weekend, urging them to vote “no” in a bid to retain their seats and preserve the KMT’s majority in the Legislative Yuan. The Democratic Progressive Party (DPP), which had largely kept its distance from the civic recall campaigns, earlier this month instructed its officials and staff to support the recall groups in a final push to protect the nation. The justification for the recalls has increasingly been framed as a “resistance” movement against China and

Chinese Minister of Foreign Affairs Wang Yi (王毅) reportedly told the EU’s top diplomat that China does not want Russia to lose in Ukraine, because the US could shift its focus to countering Beijing. Wang made the comment while meeting with EU High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy Kaja Kallas on July 2 at the 13th China-EU High-Level Strategic Dialogue in Brussels, the South China Morning Post and CNN reported. Although contrary to China’s claim of neutrality in the Russia-Ukraine conflict, such a frank remark suggests Beijing might prefer a protracted war to keep the US from focusing on