If you have ever had the pleasure of assembling IKEA furniture, then you have learned something about big infrastructure projects. The first Billy bookcase is a nightmare of fumbled screws and baffling instructions. The second goes a little smoother. The third is a breeze.

This is effectively what happens with nuclear power plants.

However, it has taken the UK 70-odd years to take that lesson on board.

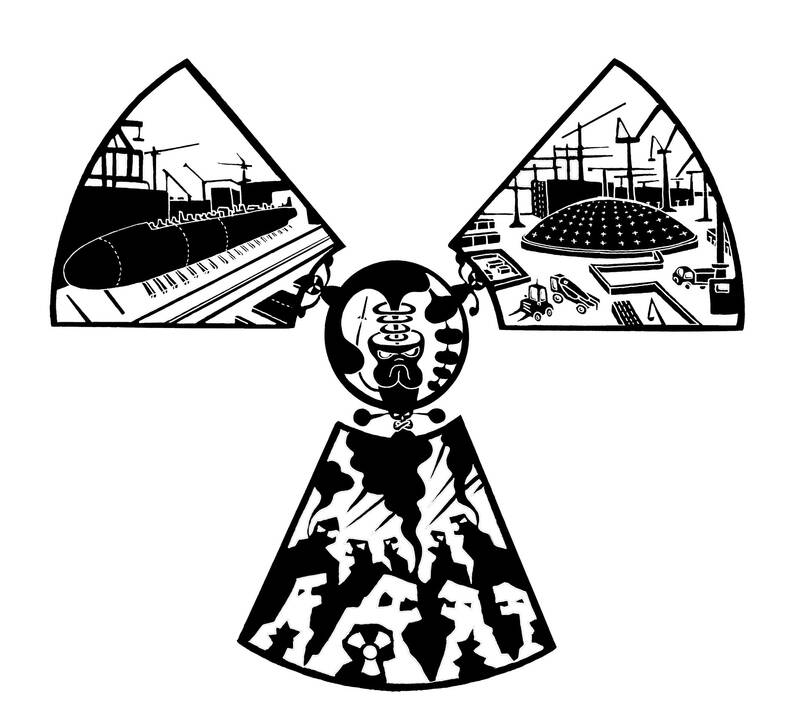

Illustration: Mountain People

The Labour government last week said that it would commit £14.2 billion (US$19.2 billion) to Sizewell C, a new nuclear power station on the Suffolk coast, as well as £2.5 billion toward Rolls-Royce Holdings PLC’s small modular reactors (SMRs), which will be the first of their kind in Europe.

This is a positive move for low-carbon energy. Nuclear power can provide large amounts of baseload electricity, which is needed to support intermittent renewables — particularly as artificial intelligence drives a huge increase in round-the-clock energy demand.

The main criticism is that it is expensive and the UK’s track record on fission has not left the public feeling encouraged. Although the UK started off as a leader on nuclear power, it is now regarded as a bit of a flop. There are lots of reasons for the decline of nuclear in Britain, including a heap of cheap gas, but I would also argue it is partly because the nation did not commit to a fleet of Billy bookcases.

Calder Hall, the UK’s first nuclear power plant, opened in 1956, and began a series of builds.

However, Adrian Bull, chair in nuclear energy and society at the University of Manchester’s Dalton Nuclear Institute, told me that with the industry being led by scientists and engineers, the temptation was to tweak every new facility to be a little bit better, a little bit bigger. That meant over the 19 operational power stations built in the UK, about 15 different designs were used.

In contrast, France has 57 reactors, but has only ever used three designs. As a result, France was able to add 50 gigawatts of nuclear energy — almost the equivalent of the UK’s peak electricity demand — to its grid in just 15 years.

Fast forward to Hinkley Point C, the first new nuclear power plant in the UK since Sizewell B, which opened in 1995. Originally intended to start generating power this year and come in at a total cost of £18 billion in 2015 values, it is now expected to cost about £46 billion and is not scheduled to open until 2031.

Some of this is bad luck: Brexit and the COVID-19 pandemic complicated and delayed construction. Some of it is also due to Britain’s stringent regulation. Although the reactor design had been used in France, China and Finland before, the British Office for Nuclear Regulation required 7,000 design modifications. As a result, Hinkley Point C represents another first-of-its-kind reactor design, with 25 percent more concrete and 35 percent more steel — materials that are the dominant cost of a nuclear power plant.

It is also likely to be so expensive and delayed because the UK simply has not built anything like it for decades. The skilled workforce did not exist at the scale needed for the project.

Where does this leave Sizewell C? The good news is that Electricite de France SA, the company developing Hinkley Point C and the new power station in Suffolk, is making faster progress on Hinkley Point C’s second reactor than the first. Components are being installed ahead of schedule, even with fewer people on site.

Crucially, Sizewell C is a direct replica — the UK has finally opted for that second Billy — so all that learning ought to be carried right over and possibly even improved.

There will be challenges, of course. Although some workers will be able to go from Somerset to Suffolk, between Sizewell C, Rolls-Royce’s SMRs and the new nuclear submarines, that is an awful lot of skilled workers that the UK needs — and does not have.

That is no bad thing, as Michael Bluck, director of the Centre for Nuclear Engineering at Imperial College, told me: “These are just the sort of jobs and skills we want for this country.”

The UK is also clearly thinking about the next generation of nuclear power plants with SMRs. Smaller reactors with factory-made modular components, SMRs promise to take the Billy bookcase analogy to another level.

The trick will be maintaining the momentum between the three government-backed Rolls-Royce units and the ones funded by the private sector that will come after. After all, another decades-long break between bookcases will put the UK nuclear industry right back at square one.

Lara Williams is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering climate change. This column reflects the personal views of the author and does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

In the first year of his second term, US President Donald Trump continued to shake the foundations of the liberal international order to realize his “America first” policy. However, amid an atmosphere of uncertainty and unpredictability, the Trump administration brought some clarity to its policy toward Taiwan. As expected, bilateral trade emerged as a major priority for the new Trump administration. To secure a favorable trade deal with Taiwan, it adopted a two-pronged strategy: First, Trump accused Taiwan of “stealing” chip business from the US, indicating that if Taipei did not address Washington’s concerns in this strategic sector, it could revisit its Taiwan

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) challenges and ignores the international rules-based order by violating Taiwanese airspace using a high-flying drone: This incident is a multi-layered challenge, including a lawfare challenge against the First Island Chain, the US, and the world. The People’s Liberation Army (PLA) defines lawfare as “controlling the enemy through the law or using the law to constrain the enemy.” Chen Yu-cheng (陳育正), an associate professor at the Graduate Institute of China Military Affairs Studies, at Taiwan’s Fu Hsing Kang College (National Defense University), argues the PLA uses lawfare to create a precedent and a new de facto legal

The stocks of rare earth companies soared on Monday following news that the Trump administration had taken a 10 percent stake in Oklahoma mining and magnet company USA Rare Earth Inc. Such is the visible benefit enjoyed by the growing number of firms that count Uncle Sam as a shareholder. Yet recent events surrounding perhaps what is the most well-known state-picked champion, Intel Corp, exposed a major unseen cost of the federal government’s unprecedented intervention in private business: the distortion of capital markets that have underpinned US growth and innovation since its founding. Prior to Intel’s Jan. 22 call with analysts

Chile has elected a new government that has the opportunity to take a fresh look at some key aspects of foreign economic policy, mainly a greater focus on Asia, including Taiwan. Still, in the great scheme of things, Chile is a small nation in Latin America, compared with giants such as Brazil and Mexico, or other major markets such as Colombia and Argentina. So why should Taiwan pay much attention to the new administration? Because the victory of Chilean president-elect Jose Antonio Kast, a right-of-center politician, can be seen as confirming that the continent is undergoing one of its periodic political shifts,