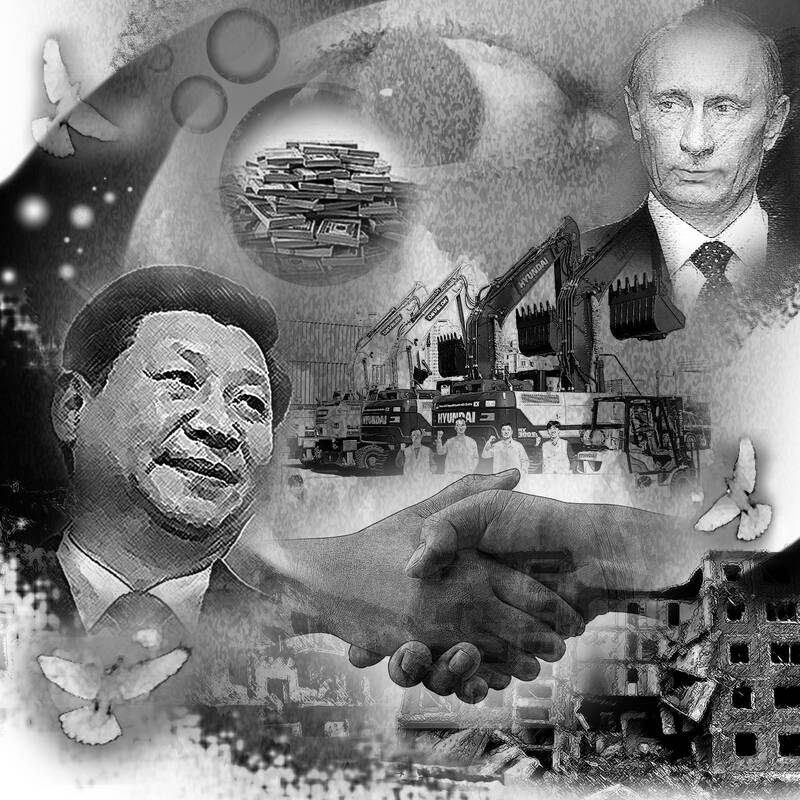

The sight of Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平) visiting the Kremlin for Russia’s World War II Victory Day parade has rekindled the idea that China might finally pressure Russian President Vladimir Putin to end the war in Ukraine.

However, it has been more than three years since Russia invaded its neighbor and little suggests that China is willing to support good-faith peace negotiations.

In fact, China has continued to back Russia diplomatically, economically and militarily. The Chinese government avoids referring to Putin’s aggression as an “invasion” and even though it has not formally recognized Russia’s annexation of Ukrainian territory, it has repeatedly abstained from UN votes condemning Putin’s war.

Illustration: Kevin Sheu

Publicly, China echoes Russia’s narrative, blaming NATO and the West for the conflict. Chinese officials and state media accuse the US of being “the real provocateur of the Ukrainian crisis” and have warned it against further confrontation.

For his part, Xi has shown no signs of reconsidering the Sino-Russia “all-weather comprehensive strategic partnership for the new era.” Over the past three years, he and Putin have met nine times in person — more than any other two world leaders. Shortly after US President Donald Trump’s inauguration this year, Xi and Putin pledged that their countries would “deepen strategic coordination, firmly support each other and defend their legitimate interests.”

Xi’s state visit this month came as China was rallying support in opposing Trump’s tariff war.

Economically, China has extended Russia a lifeline as Western sanctions have intensified. Sino-Russian bilateral trade soared from US$147 billion in 2021 to a record US$245 billion last year. Chinese consumer products, notably automobiles and smartphones, rapidly poured in as Western brands withdrew. By early 2023, Chinese smartphones accounted for more than 70 percent of the Russian market.

Similarly, China is poised to import more energy from Russia this year (likely at heavily discounted prices), which will help the Kremlin finance its war effort. Since 2023, Russia has become China’s top crude oil supplier. Despite the risk of penalties, small regional Chinese banks have continued processing payments for sanctioned Russian banks and companies. While China has not openly provided direct lethal aid, it has exported to Russia a steady stream of dual-use items, notably microchips essential for precision-guided weaponry.

Despite its close ties with Russia, China has tried to present itself as a peacemaker. In February 2023, it released a peace framework; and in May last year, it partnered with Brazil on a six-point initiative to end the war. A Chinese special envoy has since visited several countries, including Russia and Ukraine, to promote the proposal, but China’s plans amount to lofty principles with little substance. It is less interested in ending the war than in winning goodwill across the Global South and refurbishing its image in Europe.

Why should it be otherwise? China benefits strategically as long as the war stays within Ukraine, the nuclear risk remains low and its “unlimited partner,” Russia, does not lose. The conflict diverts US attention from the Indo-Pacific region, giving China more room to advance its interests. It has also deepened Russia’s political and economic dependence on China, improving China’s access to Russian resources via routes beyond the US Navy’s reach.

Meanwhile, Chinese firms in strategic sectors, such as the drone-makers DJI, EHang and Autel, have cashed in by selling products to both sides. In early 2023, direct drone shipments to Ukraine exceeded US$200,000, while shipments to Russia topped US$14.5 million. Despite sanctions, DJI’s drones continued reaching Russian forces through smaller distributors in China, the Middle East and Europe.

Even if China was truly open to facilitating peace talks, Ukraine would remain rightly skeptical of its neutrality. Xi has ignored Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskiy’s repeated requests to meet and did not speak with him until April 2023 — more than a year after Russia’s invasion. China showed limited interest in Ukraine’s 10-point peace formula, released in November 2022, and it skipped a global summit (attended by 92 countries) on the issue in June last year.

Instead, China released its joint peace proposal with Brazil, which Ukraine saw as an attempt to undermine its own peace formula and another sign that China is more interested in advancing its own agenda than in ending the war.

The US has little leverage to change China’s position. More tariffs or sanctions could backfire. China might align even more closely with Russia to thwart US negotiations and strengthen its yuan-based financial system, undermining US sanctions and economic clout.

Still, Trump could appeal to Xi’s desire for global stature. By offering China a major role in Ukraine’s reconstruction, the US would grant China’s leadership the prestige it craves.

Moreover, China would become an invested stakeholder in Ukraine’s security, providing a more sustainable deterrent against future Russian aggression.

Ukraine has been part of Xi’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) since 2017. Before Russia’s invasion, China had nearly US$3 billion in BRI-related contracts in Ukraine and had leased up to 10 percent of Ukraine’s farmland. Those investments were likely wiped out, but China did not protest; its economic loss was inconsequential compared with its strategic gains from the war.

A lasting peace could tempt China to return. Ukraine’s industrial, energy, infrastructure and agriculture sectors offer new markets for Chinese firms squeezed by overcapacity at home and rising tariffs abroad. Giving China a stake in Ukraine’s reconstruction could transform it from a passive pro-Russia bystander into an active participant in peacemaking.

The reconstruction bill will be too large for the West to foot on its own. A year ago, the World Bank estimated the costs at US$486 billion (about 2.6 percent of China’s GDP last year) over the next decade and the price tag has only risen since then. The West will have no choice but to seek assistance, including from the Gulf states and China.

However, the first task is to encourage China’s interest in engagement. Perhaps the only way to do that is to convince China’s leaders that the US will not accept Ukraine’s capitulation and will continue to support it until a just settlement is reached.

Thomas Graham, a distinguished fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations, is a research academic at the MacMillan Center and cofounder of the Russian, East European and Eurasian Studies program at Yale University, and a former senior director for Russia at the US National Security Council. Zongyuan Zoe Liu (劉宗媛), senior fellow for China studies at the Council on Foreign Relations, is adjunct assistant professor of international and public affairs at Columbia University’s School of International and Public Affairs.

Copyright: Project Syndicate

The US Senate’s passage of the 2026 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA), which urges Taiwan’s inclusion in the Rim of the Pacific (RIMPAC) exercise and allocates US$1 billion in military aid, marks yet another milestone in Washington’s growing support for Taipei. On paper, it reflects the steadiness of US commitment, but beneath this show of solidarity lies contradiction. While the US Congress builds a stable, bipartisan architecture of deterrence, US President Donald Trump repeatedly undercuts it through erratic decisions and transactional diplomacy. This dissonance not only weakens the US’ credibility abroad — it also fractures public trust within Taiwan. For decades,

In 1976, the Gang of Four was ousted. The Gang of Four was a leftist political group comprising Chinese Communist Party (CCP) members: Jiang Qing (江青), its leading figure and Mao Zedong’s (毛澤東) last wife; Zhang Chunqiao (張春橋); Yao Wenyuan (姚文元); and Wang Hongwen (王洪文). The four wielded supreme power during the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976), but when Mao died, they were overthrown and charged with crimes against China in what was in essence a political coup of the right against the left. The same type of thing might be happening again as the CCP has expelled nine top generals. Rather than a

Taiwan Retrocession Day is observed on Oct. 25 every year. The Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) government removed it from the list of annual holidays immediately following the first successful transition of power in 2000, but the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT)-led opposition reinstated it this year. For ideological reasons, it has been something of a political football in the democratic era. This year, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) designated yesterday as “Commemoration Day of Taiwan’s Restoration,” turning the event into a conceptual staging post for its “restoration” to the People’s Republic of China (PRC). The Mainland Affairs Council on Friday criticized

The topic of increased intergenerational conflict has been making headlines in the past few months, showcasing a problem that would only grow as Taiwan approaches “super-aged society” status. A striking example of that tension erupted on the Taipei MRT late last month, when an apparently able-bodied passenger kicked a 73-year-old woman across the width of the carriage. The septuagenarian had berated and hit the young commuter with her bag for sitting in a priority seat, despite regular seats being available. A video of the incident went viral online. Altercations over the yielding of MRT seats are not common, but they are