Negotiators from the US and Iran have just convened in Oman for their fourth round of nuclear talks. The two sides remain far apart on fundamental questions, they have diverging expectations and they are running out of time. However, for the first time in years, there is cause for optimism. What distinguishes this moment is not a sudden convergence of positions, but a shared recognition that diplomacy is preferable to confrontation.

Iran insists that its nuclear program is strictly for civilian purposes, and the latest US intelligence assessment concludes that it is not currently building a nuclear weapon. Nonetheless, Iran’s enrichment activities have expanded significantly since US President Donald Trump withdrew the country from the 2015 Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) in 2018. Today, Iran is a threshold nuclear state with enough 60 percent-enriched uranium to produce six nuclear weapons (if enriched to 90 percent), and the ability to “dash to a bomb” in about six months (although weaponizing a device would probably take between one and two years).

For much of the West, this situation is unacceptable. Without diplomatic progress by the end of next month, the US would be compelled to trigger a “snapback” of UN sanctions. However, that would destroy what remains of the diplomatic track, prompt Iran to withdraw from the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons and escalate the risk of a military conflict.

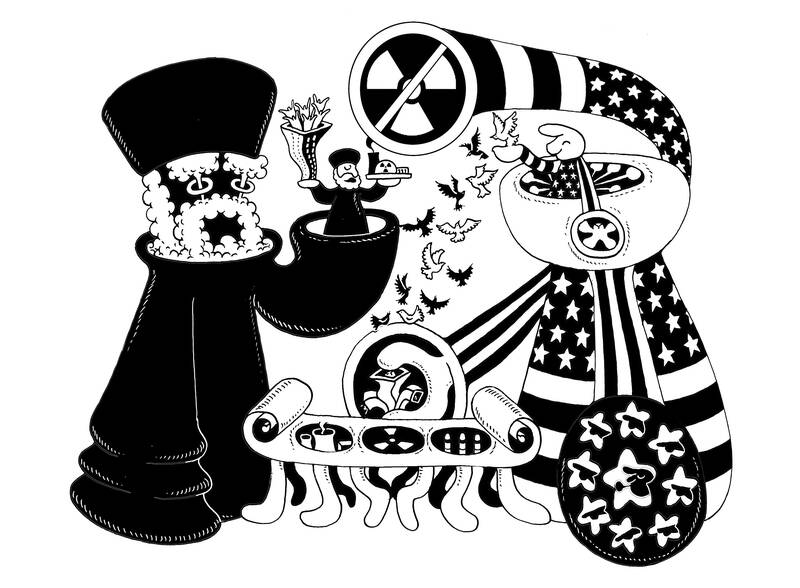

Illustration: Mountain People

Trump wants a comprehensive deal that goes beyond the JCPOA in curtailing enrichment, restraining missile development and modifying Iran’s regional behavior. However, this is a fantasy. Iran would not agree to a full rollback of its nuclear program, let alone dismantle its regional alliances — and especially not in the next few weeks. Nor would it give up enrichment or ballistic missile capabilities that are central to its deterrence posture.

Yet even in this constrained environment, a diplomatic path remains open. Both sides have incentives to accept a more limited agreement to avoid military confrontation. Trump, for all his fire and fury, is disinclined to start new wars. His recent removal of US national security adviser Michael Waltz, an Iran hawk, was telling. So was his announcement on Tuesday last week of a ceasefire with the Houthi rebels in Yemen.

Trump prefers a negotiated outcome, as do his Gulf allies, and he believes that there has never been a better time to get one, now that Iran has been so substantially weakened. With his administration’s efforts to broker a Russian-Ukrainian ceasefire faltering, the Iran file offers his best — and perhaps only — chance for a major diplomatic success before the end of the year.

Although Iran initially rejected formal engagement, its hardliners ultimately approved indirect talks via Oman, indicating a willingness to engage in direct negotiations if progress is made there. This shift reflects the Iranian regime’s recognition that continued economic and diplomatic isolation carries increasing costs. Iranian officials view sanctions relief as essential to reversing the slow collapse of the economy and containing risks to the regime from social unrest.

While the Iranians regard Trump as a hostile actor, some see his desire to secure diplomatic “wins” — and his reluctance to launch new wars — as an opportunity to obtain a reprieve without offering major concessions. Although Iran does not directly control the Houthis, it did reportedly press them to agree to the ceasefire, which addressed a key US concern — Iran’s support for regional proxies — and improved the mood for nuclear talks.

The sticking point is Iran’s enrichment capability. It has rejected US Secretary of State Marco Rubio’s suggestion that it rely on imported uranium for its civilian nuclear program, rather than enriching domestically. The Islamic Republic views enrichment as a non-negotiable sovereign right. Still, it remains open to a more limited deal that would cap enrichment, ensure verification by the International Atomic Energy Agency and provide credible assurances that it is not building a nuclear weapon.

Recent statements from the White House have also shown greater flexibility. On May 4, Trump said his main goal is to prevent Iran from acquiring a nuclear weapon, not to eliminate its civilian nuclear capacity. And on Wednesday last week, US Vice President J.D. Vance reiterated that Iran “can have civil nuclear power,” but not an enrichment program that brings it close to weapons capability. This distinction — between civilian use under strict limits and weaponization potential — could allow for a narrow agreement aimed at keeping diplomacy alive past the summer.

This is not the US’ preferred outcome, of course. Trump is notoriously impatient and would be skeptical of a deal that appears designed to string him along. However, a comprehensive agreement between parties that deeply mistrust each other cannot be negotiated in two-and-a-half months. With Trump having already threatened to bomb Iran if talks fail, a more modest deal is the only viable alternative to military confrontation. Fortunately, Trump has always shown a willingness to shift away from maximalist positions when he can claim a political victory.

If progress is made, the US would defer the sanctions snapback, either informally, by pressuring its European allies, or by seeking a new UN Security Council resolution to extend the deadline. US allies in Europe, and even Russia and China, could support such a move if it is framed as a way to avoid a crisis. This approach would preserve the option of a snapback, while keeping the diplomatic track open and holding off immediate escalation.

The military option would remain on the table. The US has expanded deployments in the region, and B-2 stealth bombers capable of carrying munitions designed to penetrate hardened targets — such as Iran’s enrichment facilities at Fordow and Natanz — are in place. These deployments serve as negotiating leverage and as preparation for potential airstrikes in case the talks fail.

There is no guarantee of success. Iran might reject US terms or overplay its hand, dragging its feet in the hope of extracting further concessions. Trump might decide that the concessions are insufficient and shift course toward a snapback, or worse. If negotiations collapse and the US or Israel attacks Iran’s nuclear facilities, Iran would retaliate against US military targets in the region and move to weaponize its nuclear program.

These are all realistic scenarios. However, despite these risks, the current round of diplomacy represents the most serious opportunity for nuclear de-escalation since the collapse of the JCPOA seven years ago.

Ian Bremmer, founder and president of Eurasia Group and GZERO Media, is a member of the executive committee of the UN High-Level Advisory Body on Artificial Intelligence.

Copyright: Project Syndicate

On May 7, 1971, Henry Kissinger planned his first, ultra-secret mission to China and pondered whether it would be better to meet his Chinese interlocutors “in Pakistan where the Pakistanis would tape the meeting — or in China where the Chinese would do the taping.” After a flicker of thought, he decided to have the Chinese do all the tape recording, translating and transcribing. Fortuitously, historians have several thousand pages of verbatim texts of Dr. Kissinger’s negotiations with his Chinese counterparts. Paradoxically, behind the scenes, Chinese stenographers prepared verbatim English language typescripts faster than they could translate and type them

More than 30 years ago when I immigrated to the US, applied for citizenship and took the 100-question civics test, the one part of the naturalization process that left the deepest impression on me was one question on the N-400 form, which asked: “Have you ever been a member of, involved in or in any way associated with any communist or totalitarian party anywhere in the world?” Answering “yes” could lead to the rejection of your application. Some people might try their luck and lie, but if exposed, the consequences could be much worse — a person could be fined,

Xiaomi Corp founder Lei Jun (雷軍) on May 22 made a high-profile announcement, giving online viewers a sneak peek at the company’s first 3-nanometer mobile processor — the Xring O1 chip — and saying it is a breakthrough in China’s chip design history. Although Xiaomi might be capable of designing chips, it lacks the ability to manufacture them. No matter how beautifully planned the blueprints are, if they cannot be mass-produced, they are nothing more than drawings on paper. The truth is that China’s chipmaking efforts are still heavily reliant on the free world — particularly on Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing

On May 13, the Legislative Yuan passed an amendment to Article 6 of the Nuclear Reactor Facilities Regulation Act (核子反應器設施管制法) that would extend the life of nuclear reactors from 40 to 60 years, thereby providing a legal basis for the extension or reactivation of nuclear power plants. On May 20, Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) legislators used their numerical advantage to pass the TPP caucus’ proposal for a public referendum that would determine whether the Ma-anshan Nuclear Power Plant should resume operations, provided it is deemed safe by the authorities. The Central Election Commission (CEC) has