Myanmar’s generals have a choice to make following the magnitude 7.7 earthquake on Friday last week.

They can repeat the mistakes of 17 years ago when they refused to allow in international help after Cyclone Nargis tore through the country, leaving 140,000 dead, or facilitate the free flow of urgent assistance.

Determined to keep Myanmar closed to the world, the junta blocked international relief efforts by banning foreign boats and aircraft from delivering supplies and delaying visas for aid workers in the first few critical weeks after the 2008 disaster. It cannot afford to take the same path this time.

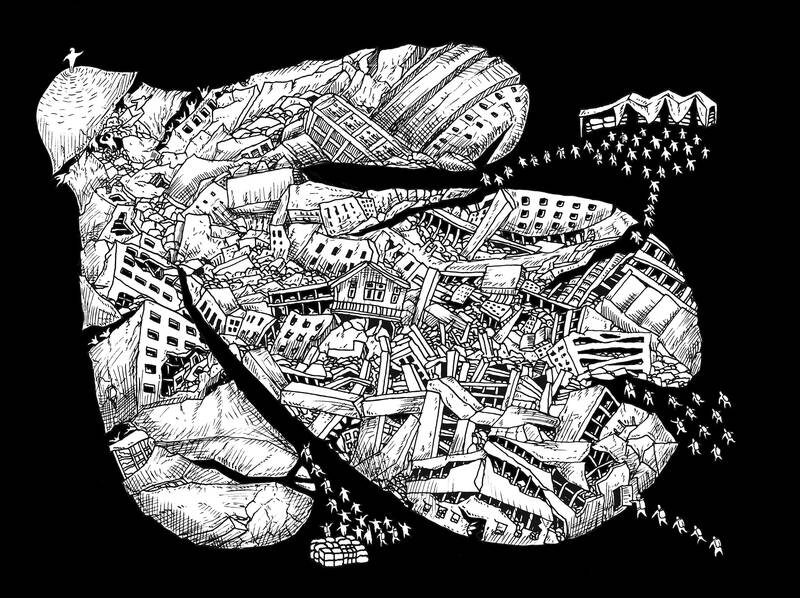

Illustration: Mountain People

Modeling from the US Geological Survey indicates that more than 10,000 people might have died in the quake, and that estimated economic losses could exceed the nation’s GDP.

So far, the generals appear to be allowing some assistance in, although it is not yet clear whether it is reaching areas held by the anti-junta resistance. Severely limited Internet access means there is little information about the true death toll other than the official tally of 2,056, with more than 3,900 injured.

That Myanmar is in the middle of a civil war is complicating rescue efforts and the distribution of aid. The regime, which took power in a coup in 2021, controls less than one-quarter of the country.

India is airlifting a mobile army hospital to Mandalay — the epicenter of the earthquake — along with a team of medics and tonnes of relief supplies. China, Russia, Israel and the UK are also providing assistance, while ASEAN said teams from Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam had been deployed. US President Donald Trump’s cuts to the US Agency for International Development have reportedly delayed and restricted help from the US.

The junta’s acceptance of aid is a significant step, and one that the international community should leverage to pry the doors open further. They also must prevent the regime from exploiting the assistance for its own gain.

Ironically, it was, in part, the junta’s decision in 2008 to eventually allow in foreign aid to deal with the cyclone’s aftermath that led to Myanmar’s gradual opening up, and the eventual election of pro-democracy forces in 2015. Citizens would be hoping something similar happens.

Anti-junta groups and ethnic armies hold the bulk of the territory, along with important infrastructure projects including Chinese-funded oil and gas pipelines and parts of the 1,400km highway that runs from the northeastern Indian state of Manipur through Myanmar to Mae Sot in Thailand.

The National Unity Government, which represents the ousted civilian administration, initiated a two-week ceasefire in quake-hit areas to allow aid to reach victims. It does not look like the junta would do the same. Instead, its warplanes continued to conduct airstrikes near the disaster zones, taking advantage of the chaos to try and gain a foothold against rebel armies.

China, India and Thailand — Myanmar’s three biggest neighbors — have an important role to play, as does the UN, which estimates that 20 million people have been affected by the quake and the magnitude 5.1 aftershock that followed on Sunday.

The EU, the UK, Australia and New Zealand, among others, have announced millions of dollars in aid. The key would be how this is distributed and whether pressure from donor nations and relief groups can convince the junta to give up its four-year-long war against its citizens.

Beijing, in particular, cannot be happy with the chaos on its border, where Myanmar’s army has clashed with armed resistance groups, forcing refugees to flee into China. It is unclear whether a Beijing-mediated ceasefire agreement that came into effect in January will hold.

Rather than prop up the junta, China should support the peace process in other parts of the country that would encourage a stable environment and help protect its investments. That is also a chance to prove its credibility as a global peacemaker, a role it has shown ambitions to play in Ukraine and elsewhere.

The Burmese army, or Tatmadaw as it is known, has perpetuated war on multiple fronts since the nation won independence from British rule in 1948. The earthquake has only exacerbated the humanitarian crisis born out of that generations-long conflict. Even before it hit, about one-third of the population was in need of humanitarian assistance, while the civil war had displaced more than 3.5 million people, including 1.6 million in the crisis-struck areas.

There is precedence for a natural disaster helping to end a long-running conflict. The Acehnese national army — the armed wing of the Free Aceh Movement in Indonesia — demobilized and disbanded a year after the 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake and tsunami destroyed much of the province, ending a 30-year separatist insurgency.

Cyclone Nargis and the tsunami have provided a road map, however imperfect. Myanmar and its backers should use it.

Ruth Pollard is a Bloomberg Opinion Managing Editor. Previously she was South and Southeast Asia government team leader at Bloomberg News and Middle East correspondent for the Sydney Morning Herald. This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

In the first year of his second term, US President Donald Trump continued to shake the foundations of the liberal international order to realize his “America first” policy. However, amid an atmosphere of uncertainty and unpredictability, the Trump administration brought some clarity to its policy toward Taiwan. As expected, bilateral trade emerged as a major priority for the new Trump administration. To secure a favorable trade deal with Taiwan, it adopted a two-pronged strategy: First, Trump accused Taiwan of “stealing” chip business from the US, indicating that if Taipei did not address Washington’s concerns in this strategic sector, it could revisit its Taiwan

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) challenges and ignores the international rules-based order by violating Taiwanese airspace using a high-flying drone: This incident is a multi-layered challenge, including a lawfare challenge against the First Island Chain, the US, and the world. The People’s Liberation Army (PLA) defines lawfare as “controlling the enemy through the law or using the law to constrain the enemy.” Chen Yu-cheng (陳育正), an associate professor at the Graduate Institute of China Military Affairs Studies, at Taiwan’s Fu Hsing Kang College (National Defense University), argues the PLA uses lawfare to create a precedent and a new de facto legal

Chile has elected a new government that has the opportunity to take a fresh look at some key aspects of foreign economic policy, mainly a greater focus on Asia, including Taiwan. Still, in the great scheme of things, Chile is a small nation in Latin America, compared with giants such as Brazil and Mexico, or other major markets such as Colombia and Argentina. So why should Taiwan pay much attention to the new administration? Because the victory of Chilean president-elect Jose Antonio Kast, a right-of-center politician, can be seen as confirming that the continent is undergoing one of its periodic political shifts,

The stocks of rare earth companies soared on Monday following news that the Trump administration had taken a 10 percent stake in Oklahoma mining and magnet company USA Rare Earth Inc. Such is the visible benefit enjoyed by the growing number of firms that count Uncle Sam as a shareholder. Yet recent events surrounding perhaps what is the most well-known state-picked champion, Intel Corp, exposed a major unseen cost of the federal government’s unprecedented intervention in private business: the distortion of capital markets that have underpinned US growth and innovation since its founding. Prior to Intel’s Jan. 22 call with analysts