Mention “proliferation” and most people would assume that you are talking about the spread of nuclear weapons. For good reason. Nine countries (China, France, India, Israel, North Korea, Pakistan, Russia, the US and the UK) possess them. However, many more have the ability and conceivably the motive to produce them. There is also the danger that terrorist groups could obtain one or more of these weapons, enabling them to inflict horrific damage.

This sort of proliferation is often described as “horizontal.” The biggest immediate focus remains Iran, which has dramatically reduced the time it would require to develop one or more nuclear devices. An Iran with nuclear weapons might use them — or, even if not, might calculate that it could safely coerce or attack Israel or one or more of its Arab neighbors directly (or through one of its proxies) with non-nuclear, conventional weapons.

A nuclear-armed Iran would likely trigger a regional arms race. Several of its neighbors — particularly Saudi Arabia, Egypt, the United Arab Emirates and Turkey — might well develop or acquire nuclear weapons of their own. Such a dynamic would further destabilize the world’s most troubled and volatile region.

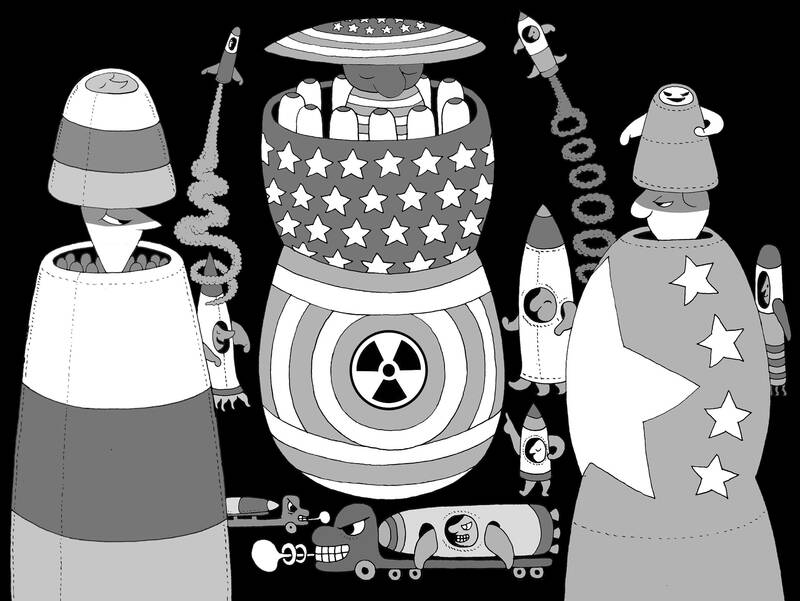

Illustration: Mountain People

However, as important as this scenario is, another type of proliferation now merits attention: Vertical proliferation, namely, increases in the quality and/or quantity of the nuclear arsenals of the nine countries that already possess these weapons. The danger is not only that nuclear weapons might be used in a war, but also that the possibility of war would increase by emboldening governments — like Iran in the scenario above — to act more aggressively in pursuit of their geopolitical goals in the belief that they can act with impunity.

The fastest-growing nuclear arsenal in the world today belongs to China. It would appear that China believes that if it can match the US in this realm, it can deter the US from intervening on Taiwan’s behalf during any crisis over the nation. China is on pace to catch up to the US and Russia in a decade — and is showing no interest either in participating in arms-control talks that would slow down its buildup or place a ceiling on its capabilities.

Then there is North Korea. Neither economic sanctions nor diplomacy has succeeded in curtailing its nuclear program. North Korea is now thought to possess more than 50 warheads. Some are on missiles with intercontinental range and improving accuracy. China and Russia have assisted it, and further Russian assistance is likely, given North Korea’s provision of weapons to Russia for use in Ukraine.

Again, the question is not only what North Korea might do with its nuclear arsenal. It is not far-fetched to imagine a North Korean attack on South Korea or even Japan using conventional forces, coupled with a nuclear-backed threat to the US not to intervene. It is precisely this possibility that is fueling public pressure in South Korea to develop nuclear weapons, demonstrating that vertical proliferation can trigger horizontal proliferation, especially if countries protected by the US come to doubt its willingness to put itself at risk to defend them.

Russia offers another reason for worry. Russia and the US have the world’s two largest nuclear arsenals. Both are constrained by an arms-control agreement (the New START Treaty) that limits the number of nuclear warheads that each can deploy to 1,550. (Additional warheads may be kept in storage, though.)

The agreement also limits how many launchers (planes, missiles and submarines) carrying nuclear weapons can be fielded and includes various arrangements to facilitate verification so that the two governments can be confident that the other is complying.

New START (ratified in 2011 and extended several times since) is due to expire in February 2026. Russia might well refuse to extend the treaty again, possibly because the performance of its armed forces in Ukraine has left it more dependent than ever on its nuclear arsenal, or it might seek to barter its willingness to continue abiding by the agreement for US concessions on Ukraine.

What worries Washington is not only what Russia might do, but also that the US now faces three adversaries with nuclear weapons who could coordinate their policies and pose a unified nuclear front in a crisis. All of this is prompting the US to rethink its own nuclear posture.

The US government in March reportedly completed its periodic review of its nuclear forces. At a minimum, billions of dollars would be spent on a new generation of bombers, missiles and submarines. At worst, we could be entering an era of unstructured nuclear competition.

It all adds up to a dangerous moment. The taboo associated with nuclear weapons has grown weaker with time; few today were alive when the US used nuclear weapons twice against Japan to hasten World War II’s end. Indeed, Russian officials have hinted strongly at their readiness to use nuclear weapons in the context of the war in Ukraine.

Nuclear weapons played a stabilizing role during the Cold War. Arguably, their existence helped keep it cold. However, there were only two decision makers and each had an inventory that could survive a first strike by the other, enabling it to retaliate in kind, thereby strengthening deterrence. Both sides mostly acted with a degree of caution, lest their competition escalate to direct conflict and precipitate a disastrous nuclear exchange.

Three and a half decades after the Cold War’s end, a new world is emerging, one characterized by nuclear arms races, potential new entrants into an ever less exclusive nuclear-weapons club and a long list of deep disagreements over political arrangements in the Middle East, Europe and Asia. This is not a situation that lends itself to a solution, but at best to effective management. One can only hope the leaders of this era would be up to the challenge.

Richard Haass, president emeritus of the Council on Foreign Relations, is a senior counselor at Centerview Partners and the author of The Bill of Obligations: The Ten Habits of Good Citizens and the weekly newsletter Home & Away.

Copyright: Project Syndicate

In their recent op-ed “Trump Should Rein In Taiwan” in Foreign Policy magazine, Christopher Chivvis and Stephen Wertheim argued that the US should pressure President William Lai (賴清德) to “tone it down” to de-escalate tensions in the Taiwan Strait — as if Taiwan’s words are more of a threat to peace than Beijing’s actions. It is an old argument dressed up in new concern: that Washington must rein in Taipei to avoid war. However, this narrative gets it backward. Taiwan is not the problem; China is. Calls for a so-called “grand bargain” with Beijing — where the US pressures Taiwan into concessions

The term “assassin’s mace” originates from Chinese folklore, describing a concealed weapon used by a weaker hero to defeat a stronger adversary with an unexpected strike. In more general military parlance, the concept refers to an asymmetric capability that targets a critical vulnerability of an adversary. China has found its modern equivalent of the assassin’s mace with its high-altitude electromagnetic pulse (HEMP) weapons, which are nuclear warheads detonated at a high altitude, emitting intense electromagnetic radiation capable of disabling and destroying electronics. An assassin’s mace weapon possesses two essential characteristics: strategic surprise and the ability to neutralize a core dependency.

Chinese President and Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Chairman Xi Jinping (習近平) said in a politburo speech late last month that his party must protect the “bottom line” to prevent systemic threats. The tone of his address was grave, revealing deep anxieties about China’s current state of affairs. Essentially, what he worries most about is systemic threats to China’s normal development as a country. The US-China trade war has turned white hot: China’s export orders have plummeted, Chinese firms and enterprises are shutting up shop, and local debt risks are mounting daily, causing China’s economy to flag externally and hemorrhage internally. China’s

During the “426 rally” organized by the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and the Taiwan People’s Party under the slogan “fight green communism, resist dictatorship,” leaders from the two opposition parties framed it as a battle against an allegedly authoritarian administration led by President William Lai (賴清德). While criticism of the government can be a healthy expression of a vibrant, pluralistic society, and protests are quite common in Taiwan, the discourse of the 426 rally nonetheless betrayed troubling signs of collective amnesia. Specifically, the KMT, which imposed 38 years of martial law in Taiwan from 1949 to 1987, has never fully faced its