Lashed by torrential rains and scorched by brutal heatwaves, Dhaka’s workers — from rickshaw drivers to those working in clothes factories — are exposed more than most to the reality of the climate emergency.

Bangladesh’s capital, one of the world’s most congested and polluted megacities, is home to about 10 million people, including thousands who have fled floods and droughts in other parts of a country that is on the frontline of climate change.

Managing these huge numbers while also climate-proofing the riverside city is a huge challenge, but it is an urgent one that city authorities are hoping to address with their first climate action plan, which was launched in May.

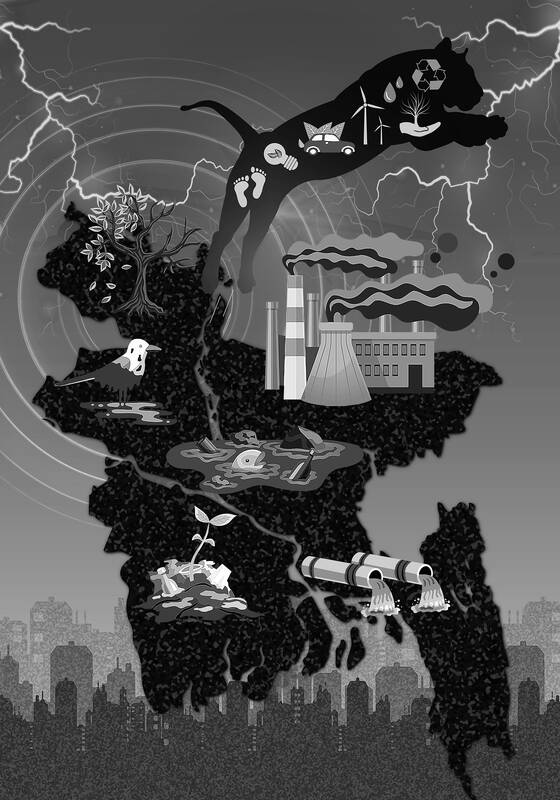

Illustration: Louise Ting

“Transforming Dhaka was critical towards making Bangladesh green and climate-resilient,” Bangladeshi Minister of Environment Saber Hossain Chowdhury said at the launch.

The plan will serve as a roadmap to enable the city to become carbon-neutral by 2050, and includes strategies to help it cope with ever more frequent floods and heatwaves.

It includes proposals to switch to renewable energy sources, introduce electric vehicles, increase green spaces, restore natural drainage systems, establish early flood warning systems and ensure a secure water supply by 2030.

Dhaka is just the latest city in the region to seek to face the climate challenge head-on.

Asia was the world’s most disaster-hit region from climate hazards last year, including floods, storms and heatwaves, and the region is also warming faster than other areas, the World Meteorological Organization said.

With about 704 million people living in urban areas in South Asia, the race is on to equip cities for a hotter, more dangerous future.

First of all, cities must set baselines for greenhouse gas emissions and risks so that they can measure progress over time, said Shruti Narayan, managing director at the C40 Cities network, a global network of cities working on climate action.

“Data-driven targets and monitoring is critical to turning the plans into reality,” Narayan told the Thomson Reuters Foundation.

The C40 platform helps cities align their climate plans with the 2015 Paris Agreement to limit global warming to “well below” 2°C.

More than 60 cities have announced such plans under the platform so far, including some of Asia’s biggest urban areas.

The Indian cities of Mumbai, Chennai and Bengaluru have already adopted climate plans, and Karachi in Pakistan is drawing up its own blueprint.

The stakes are high: The Asian Development Bank says that unless planet-heating emissions are cut, the collective economy of six countries — Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, the Maldives, Nepal and Sri Lanka — could shrink by up to 1.8 percent every year by 2050 and 8.8 percent by 2100 on average.

Already, the livelihoods of more than 200 million people in these countries are threatened by the rapid loss of snow cover in the Himalayas and rising sea levels, the bank said.

FINANCING GREEN AMBITIONS

Cities consume two-thirds of the world’s energy and house 50 percent of the global population. More than 10,000 cities have committed to cutting emissions and adapting to climate hazards.

As part of its climate plan, Dhaka’s twin municipalities — north and south — established emissions inventories for 2021-2022 by identifying the most polluting sectors and then set a target of cutting 70 percent of emissions by 2050.

One challenge is financing the required changes; cities in the Global South have long complained about richer countries not paying their fair share to cover the costs of climate change.

This year’s COP29 climate summit in Azerbaijan is expected to focus on setting a goal for the levels of climate finance that will be needed from 2025 onward to help poorer nations curb emissions, adapt to worsening extreme weather and higher seas, and respond to unavoidable climate “loss and damage.”

In the meantime, some cities in the Global South have invested in innovative digital tools, such as digital twins, to build climate resilience, while others scramble for resources.

Mumbai — the richest municipality in India with an annual budget of nearly 600 billion rupees (US$7.2 billion) in 2024-2025 — allocated about 100 billion rupees for climate actions such as expanding tree cover, reviving urban parks and managing floods.

Mumbai’s climate allocation dwarfs the entire budget of northern Dhaka — 53 billion taka (US$450.3 million) in 2023-2024 — which means the resource-strapped city must prioritize cheaper actions, said Md Sirajul Islam, chief town planner of Dhaka South City Corp.

Jaya Dhindaw, head of the South Asian chapter of the World Resources Institute that developed the climate plans for several Indian cities, said realistic, achievable actions help set the pace for progress.

For example, early last month, Bengaluru’s deputy chief minister announced extended opening hours for urban parks to provide shade for the city’s people.

“With low-hanging actions like these, you can drive cities’ confidence that climate actions are doable projects,” Dhindaw said.

However, Dhaka will need funding to raise the share of renewable power to 85 percent, treat a massive amount of organic waste to stem methane emissions and ensure that 95 percent of vehicles are electric.

The city might need to call on global donors, said Jubaer Rashid, the Bangladesh country representative of Local Governments for Sustainability, a global network of local and national governments.

“We will work closely with city officials to help them develop proposals for fundraising,” said Rashid, who worked with Dhaka’s municipalities on their climate plans.

CITIES REIMAGINED

Urban planners and environmental activists said that another priority must be pushing back against the poor planning that has exacerbated problems caused by the changing climate.

For example, in the northern part of Dhaka, green cover has shrunk by 66 percent in the past three decades alone, with canals and fields destroyed to make space for densely populated residential zones.

The city’s rapid, unplanned growth has choked rivers like the Buriganga and blocked drains, causing worse flooding, said urban planner Mehedi Ahsan, who represents the International Union for Conservation of Nature in Bangladesh.

The climate action plan aims to restore the canals and expand green spaces to cover 25 percent of the city by 2050.

However, with up to 2,000 people arriving in northern Dhaka every day, including many fleeing floods and droughts in other parts of the country, time is not on the authorities’ side.

“The place we got ourselves into is not created by the climate crisis alone, but the city climate plan provides us a hitch to shift away from a predatory pattern of building cities to protecting our ecology as we imagine a different future,” Ahsan said.

We are used to hearing that whenever something happens, it means Taiwan is about to fall to China. Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平) cannot change the color of his socks without China experts claiming it means an invasion is imminent. So, it is no surprise that what happened in Venezuela over the weekend triggered the knee-jerk reaction of saying that Taiwan is next. That is not an opinion on whether US President Donald Trump was right to remove Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro the way he did or if it is good for Venezuela and the world. There are other, more qualified

China’s recent aggressive military posture around Taiwan simply reflects the truth that China is a millennium behind, as Kobe City Councilor Norihiro Uehata has commented. While democratic countries work for peace, prosperity and progress, authoritarian countries such as Russia and China only care about territorial expansion, superpower status and world dominance, while their people suffer. Two millennia ago, the ancient Chinese philosopher Mencius (孟子) would have advised Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平) that “people are the most important, state is lesser, and the ruler is the least important.” In fact, the reverse order is causing the great depression in China right now,

This should be the year in which the democracies, especially those in East Asia, lose their fear of the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) “one China principle” plus its nuclear “Cognitive Warfare” coercion strategies, all designed to achieve hegemony without fighting. For 2025, stoking regional and global fear was a major goal for the CCP and its People’s Liberation Army (PLA), following on Mao Zedong’s (毛澤東) Little Red Book admonition, “We must be ruthless to our enemies; we must overpower and annihilate them.” But on Dec. 17, 2025, the Trump Administration demonstrated direct defiance of CCP terror with its record US$11.1 billion arms

As technological change sweeps across the world, the focus of education has undergone an inevitable shift toward artificial intelligence (AI) and digital learning. However, the HundrED Global Collection 2026 report has a message that Taiwanese society and education policymakers would do well to reflect on. In the age of AI, the scarcest resource in education is not advanced computing power, but people; and the most urgent global educational crisis is not technological backwardness, but teacher well-being and retention. Covering 52 countries, the report from HundrED, a Finnish nonprofit that reviews and compiles innovative solutions in education from around the world, highlights a