Following his party’s decisive loss to the far-right National Rally in the European Parliament election, French President Emmanuel Macron shocked everyone by dissolving the French National Assembly and calling a snap election.

He has justified his decision by saying that an election would “clarify” the political situation, but his compatriots do not share this view.

Even those who do not fear that Macron’s gamble will bring the far right to power are anxious about the chaos that might ensue.

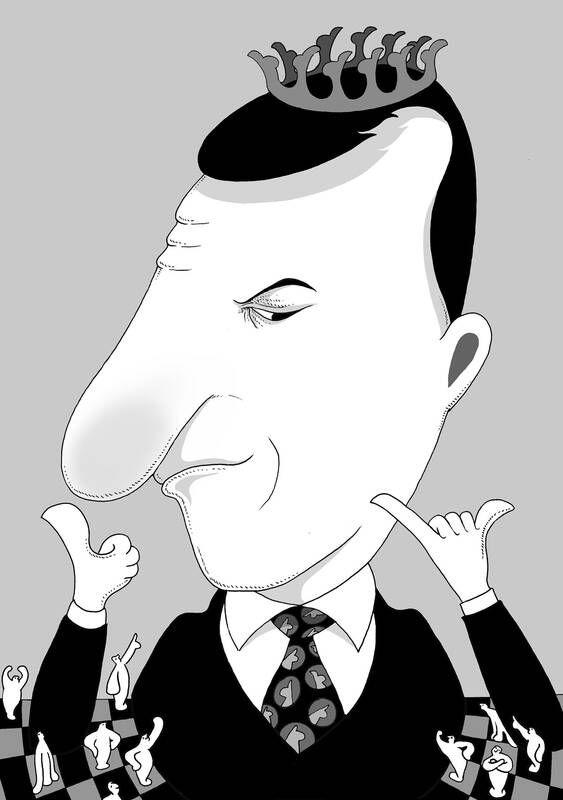

Illustration: Mountain People

The president has needlessly “killed the presidential majority,” said former French prime minister Edouard Philippe, who served in the position alongside Macron from 2017 to 2020.

A hung parliament with National Rally as the largest party is considered the most likely outcome. Still, Macron’s decision has clarified one thing: His strategy to create a powerful centrism in France has failed. Other European leaders should take note.

Legend has it that the first question Napoleon would ask about a military officer was not whether he was talented, but whether he was lucky. When Macron triumphed in the 2017 presidential election, he was extraordinarily lucky. The incumbent was so unpopular that he did not even bother to run for a second term, and the likely conservative winner was felled by a scandal. Macron seized the moment to offer what one might call a Second Coming of the “Third Way.”

Just like former British prime minister Tony Blair, Macron held that the old ideological cleavage of left and right was outdated, and that centrists should simply pick the policies that “worked best.”

Macron appealed to socialists and conservative Gaullists, on the assumption that all reasonable people could unite happily in the moderate middle. Anyone who rejected the invitation was, by definition, an unreasonable extremist.

For a while, this approach had traction, because Macron’s seemingly ever-expanding center was flanked by Marine le Pen’s National Front (now National Rally) on the far right and by firebrand Jean-luc Melenchon’s France Unbowed on the far left.

Yet the technocratic approach — “if you’re not with us, you’re unreasonable” — ultimately failed to transform the political landscape.

The far right, far left, center left and center right each still tend to win at least one-fifth of the vote in the first round of French presidential elections, on average.

However, the center-right Republicans have been hemorrhaging votes to National Rally, prompting Republicans leader Eric Ciotti to endorse an alliance with the far right. This matters, because Macron’s overwhelming support in the second round of the 2017 and 2022 elections — when he was facing off against Le Pen — was largely due to voters’ hostility to the far-right, not enthusiasm for Macron-style technocracy.

On the contrary, technocracy tends to provoke a backlash, because it creates an opportunity for populists to argue — reasonably — that there are no uniquely rational solutions to complex problems, and that democracy is supposed to be about choice and popular participation, not elites decreeing that there is no alternative.

Macron’s haughty style — already in 2017, he let it be known that he wanted to rule like “Jupiter” — certainly did not help. Right or wrong, it has made him an exceptionally hated political figure.

Yet quite apart from the personal failings of a man who fancies himself a philosopher-king, a centrist project aimed at taking the best from the left and the right was always more likely to alienate both than to harmonize their opposing agendas.

Once Macron lost control of the National Assembly in 2022, then-French prime minister Elisabeth Borne heroically tried to cobble together ad hoc majorities to advance the president’s agenda.

However, on more than 20 occasions, she resorted to constitutional shortcuts to ram through measures that clearly lacked popular support.

Macron’s centrism not only looked increasingly authoritarian; it also acquired a rightward tilt. Hence, his hardline interior minister went so far as to accuse Le Pen of being soft on Islamism, and Borne introduced an immigration law that seemed to legitimize what the far right had been saying all along. If you are constantly tacking rightward, you eventually reach a point where you can no longer blackmail voters with the argument that you are the only thing standing in the way of right-wing extremism and the end of the Republic.

Some commentators speculate that Macron wants the National Rally to govern until the 2027 presidential election, on the grounds that it would prove itself incompetent and set the stage for a triumphant shift back toward the center.

Yet this kind of quasi-pedagogical project — with the headmaster showing his pupils that the substitute teacher does not know how to do the job — is misguided for several reasons.

For starters, not all far-right populists have overly simplistic policy ideas or are amateur administrators. Even in cases where they do show themselves to be incompetent, their fortunes can recover.

When Austria’s Machiavellian Christian Democratic chancellor, Wolfgang Schissel, brought Jorg Haider’s far-right Freedom Party into government in 2000, the populists did descend into infighting and revealed their incompetence and corruption.

Yet after splitting up and licking its wounds, the Freedom Party sailed to victory in last month’s European elections.

Moreover, as the French system allows for “cohabitation” — when the president and the prime minister belong to opposing parties — a governing party that appears incompetent can simply blame the other side for tying its hands.

Wielding the extraordinary powers of the French presidency, Macron would doubtless find an outlet on the international stage, but it is sobering to see that his vision has been downgraded from a “revolution” in 2017 to a “renaissance” in 2022 to what it is today.

Macron failed to transform the movement he started into a proper political party that is not dependent on a charismatic leader. With his charisma gone, the center’s prospects for 2027 look bleak indeed.

Jan-Werner Mueller, professor of politics at Princeton University, is the author, most recently, of Democracy Rules.

Copyright: Project Syndicate

A few weeks ago in Kaohsiung, tech mogul turned political pundit Robert Tsao (曹興誠) joined Western Washington University professor Chen Shih-fen (陳時奮) for a public forum in support of Taiwan’s recall campaign. Kaohsiung, already the most Taiwanese independence-minded city in Taiwan, was not in need of a recall. So Chen took a different approach: He made the case that unification with China would be too expensive to work. The argument was unusual. Most of the time, we hear that Taiwan should remain free out of respect for democracy and self-determination, but cost? That is not part of the usual script, and

Behind the gloating, the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) must be letting out a big sigh of relief. Its powerful party machine saved the day, but it took that much effort just to survive a challenge mounted by a humble group of active citizens, and in areas where the KMT is historically strong. On the other hand, the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) must now realize how toxic a brand it has become to many voters. The campaigners’ amateurism is what made them feel valid and authentic, but when the DPP belatedly inserted itself into the campaign, it did more harm than good. The

For nearly eight decades, Taiwan has provided a home for, and shielded and nurtured, the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). After losing the Chinese Civil War in 1949, the KMT fled to Taiwan, bringing with it hundreds of thousands of soldiers, along with people who would go on to become public servants and educators. The party settled and prospered in Taiwan, and it developed and governed the nation. Taiwan gave the party a second chance. It was Taiwanese who rebuilt order from the ruins of war, through their own sweat and tears. It was Taiwanese who joined forces with democratic activists

Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫) held a news conference to celebrate his party’s success in surviving Saturday’s mass recall vote, shortly after the final results were confirmed. While the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) would have much preferred a different result, it was not a defeat for the DPP in the same sense that it was a victory for the KMT: Only KMT legislators were facing recalls. That alone should have given Chu cause to reflect, acknowledge any fault, or perhaps even consider apologizing to his party and the nation. However, based on his speech, Chu showed