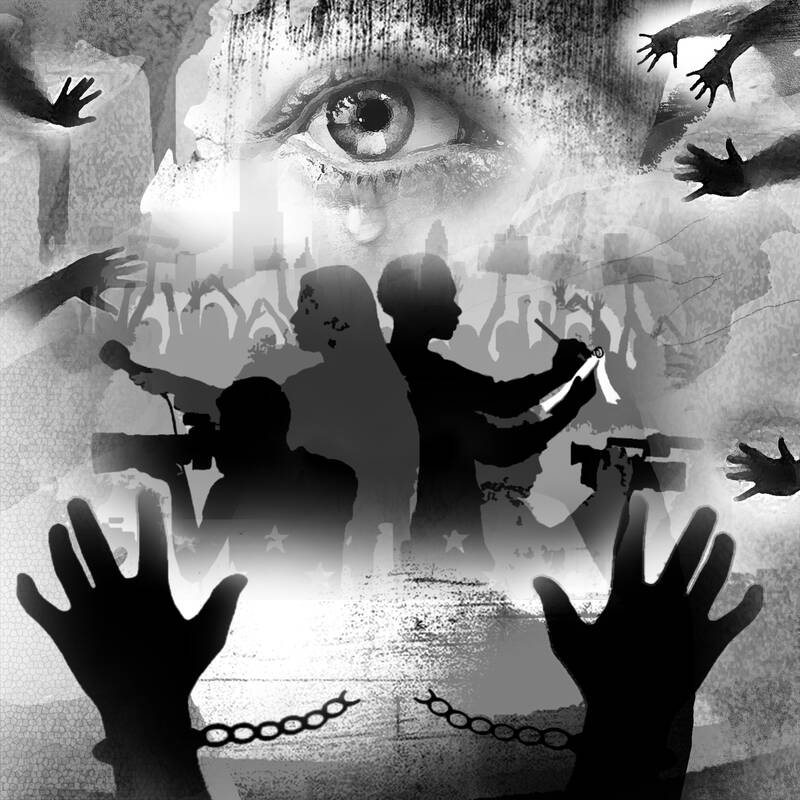

In just the first week of this year, at least 18 journalists were assaulted or harassed while covering alleged election irregularities and violence in Bangladesh. Then, in early February, journalists in Pakistan were hindered from covering elections by a wave of violence, widespread Internet blackouts and mobile-network suspensions. In March, journalists in Turkey had been shot at and banned from observing local elections, despite their legal right to do so. It was a worrying, but not especially surprising, start to this “super election year.” With half the world’s population casting ballots, independent reporting on the candidates and the issues is essential.

However, attacks on the media are rising, even in more mature democracies. In the US, former US president Donald Trump’s return as a candidate has brought back fresh memories of Jan. 6, 2021, when his supporters stormed the US Capitol, lunged at journalists and destroyed their cameras, and scribbled “Murder the media” on the doors. Such examples are illustrative of a broader problem. From the US to India, hard-won freedoms and rights are being eroded. Last year, the University of Gothenburg’s V-Dem Institute, which monitors democracy around the world, published a report saying that the progress made toward democratization since 1989 is being reversed. The authors identified increased attacks on journalists as a leading indicator of a shift toward authoritarianism.

“Aspects of freedom of expression and the media are the ones ‘wannabe dictators’ attack the most and often first,” they said.

Illustration: Kevin Sheu

A WORRYING TREND

There is no doubt that threats to journalists are on the rise, and not just in countries where independent media is always a target. Over the past three years, the Committee to Protect Journalists has documented near-record numbers of journalists (and even top media executives) behind bars, including in supposed democracies such as Guatemala, and in places that once enjoyed relatively high levels of personal and political freedom, such as Hong Kong.

Journalist killings are at their highest levels in almost a decade. In 2022, the US investigative journalist Jeff German was stabbed outside his home in Las Vegas, and a politician who German had reported on is awaiting trial for the murder. From Washington and Westminster to Buenos Aires and Budapest, journalists who cover politics receive death threats daily and are increasingly vulnerable to being targeted at political rallies and protests.

According to a 2021 UNESCO report, three-quarters of women journalists surveyed had experienced online hate, harassment or threats of violence. Among the most likely triggers for such abuse was reporting on “politics and elections.” Women and those from marginalized communities bear the brunt of this anti-media harassment online, and the vitriol frequently spills over into real-world violence.

PUBLIC INTEREST

The consequences of this disturbing trend are not limited to the media. Attacks on journalists harm all people. Journalists perform the public’s due diligence on candidates, probing their professional records, the veracity of their claims and the credibility of their promises. By reporting on policy achievements and failures, they help corroborate — or contradict — a candidate’s official narrative, exposing lies and smear campaigns for what they are. They also provide practical information about voting processes, and monitor for electoral irregularities and campaign-finance contraventions. Without such information, there can be no democracy, but rather what V-Dem calls “electoral autocracy,” where elections are empty rituals.

Independent reporting is also crucial for holding accountable those already in power. It was old-fashioned, pound-the-pavement reporting that exposed former Republican representative George Santos’ falsified biography, ultimately leading to his ejection from the US Congress (not to mention criminal charges). It was the news media that aired recordings of Peru’s secret-police chief, Vladimiro Montesinos Torres, bribing judges and politicians — revelations that would lead to the downfall of former Peruvian president Alberto Fujimori. It was independent reporting on “Partygate” that ultimately forced Boris Johnson out as prime minister of the UK.

Independent, professional journalism — both local and national — is even more important now that misinformation and disinformation are flooding into the public domain. A report by The Associated Press found that artificial intelligence is “supercharging” the spread of election lies through deepfake images and audio that is impossible to distinguish from authentic recordings. Similarly, a study released in March by the Africa Center for Strategic Studies found that disinformation had increased fourfold (compared with 2022) ahead of elections across the continent.

Independent news media are essential to counter this technology-driven trend. Consider Taiwan’s election earlier this year. Although lies flooded online channels throughout the campaign, studies suggest that much of the disinformation was defused by the combined efforts of local media, election authorities and fact-checkers, all of whom deliberately focused on building trust and furnishing voters with what they needed to make an informed and meaningful choice.

People now need to heed these lessons and watch carefully for warning signs. If this year is a litmus test for democracy around the world, a preindicator would be how the media are treated. We would have to remain vigilant in defending a free and independent press, and in championing a vibrant and curious local media. If we do not, you can be certain that the erosion of freedoms will not stop with journalists.

Copyright: Project Syndicate

Speaking at the Copenhagen Democracy Summit on May 13, former president Tsai Ing-wen (蔡英文) said that democracies must remain united and that “Taiwan’s security is essential to regional stability and to defending democratic values amid mounting authoritarianism.” Earlier that day, Tsai had met with a group of Danish parliamentarians led by Danish Parliament Speaker Pia Kjaersgaard, who has visited Taiwan many times, most recently in November last year, when she met with President William Lai (賴清德) at the Presidential Office. Kjaersgaard had told Lai: “I can assure you that ... you can count on us. You can count on our support

Denmark has consistently defended Greenland in light of US President Donald Trump’s interests and has provided unwavering support to Ukraine during its war with Russia. Denmark can be proud of its clear support for peoples’ democratic right to determine their own future. However, this democratic ideal completely falls apart when it comes to Taiwan — and it raises important questions about Denmark’s commitment to supporting democracies. Taiwan lives under daily military threats from China, which seeks to take over Taiwan, by force if necessary — an annexation that only a very small minority in Taiwan supports. Denmark has given China a

Many local news media over the past week have reported on Internet personality Holger Chen’s (陳之漢) first visit to China between Tuesday last week and yesterday, as remarks he made during a live stream have sparked wide discussions and strong criticism across the Taiwan Strait. Chen, better known as Kuan Chang (館長), is a former gang member turned fitness celebrity and businessman. He is known for his live streams, which are full of foul-mouthed and hypermasculine commentary. He had previously spoken out against the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and criticized Taiwanese who “enjoy the freedom in Taiwan, but want China’s money”

A high-school student surnamed Yang (楊) gained admissions to several prestigious medical schools recently. However, when Yang shared his “learning portfolio” on social media, he was caught exaggerating and even falsifying content, and his admissions were revoked. Now he has to take the “advanced subjects test” scheduled for next month. With his outstanding performance in the general scholastic ability test (GSAT), Yang successfully gained admissions to five prestigious medical schools. However, his university dreams have now been frustrated by the “flaws” in his learning portfolio. This is a wake-up call not only for students, but also teachers. Yang did make a big