It is that time of the year again — when educated people everywhere take a break from the office, disconnect their electronic devices and reread Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain. Pushy people might have flown to the World Economic Forum’s (WEF) annual gathering in Switzerland and shuffled from meeting to meeting. Sophisticated people, though, prefer to lose themselves in the Davos of Mann’s imagination.

It is not just that the novel is one of the masterpieces of literature, while Davos deals in corporate boilerplate. It is that Mann’s 1924 work still has far more to teach us about the state of today’s world than any number of politicians, central bankers and opinion leaders.

The annual meeting of the WEF is a vast exercise in decadence. What could be more decadent than traveling across the world in a private jet to discuss “net zero and climate-positive policies”? Or boasting about diversity, equity and inclusion when you pay yourself three hundred times as much as your frontline workers?

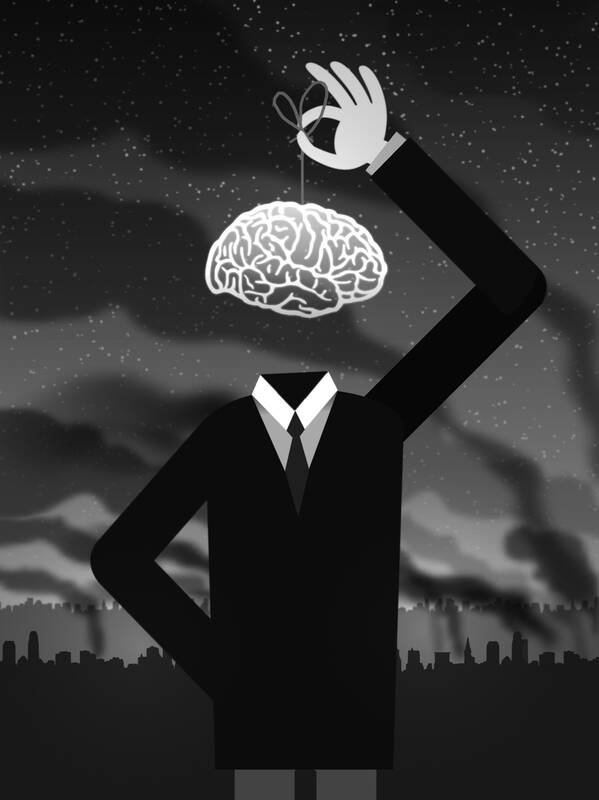

Illustration: Yusha

The theme of this year’s conference was “rebuilding trust” — as if a jamboree of the well-heeled and well-connected in an exclusive ski resort would do anything other than further erode trust in the global establishment. How fitting that the first day of the conference was marked by a resounding victory for former US president Donald Trump in the Iowa Republican caucus.

Mann said everything that is worth saying about decadence in The Magic Mountain — and you could absorb his wisdom without risking your neck rushing from one overcrowded WEF panel to another. The book was based on his stay, together with his wife, in a sanatorium in Davos in 1912, but it turned into an allegory of the morbid state of the whole of German culture.

It tells the story of Hans Castorp, a young German engineer who visits his cousin in a sanitorium for people suffering from tuberculosis. He intends to stay for three weeks but, after briefly falling ill, ends up staying for seven years, warned by doctors that his brief illness might be a symptom of something more serious. He is quickly seduced by the routine life of the place, with its gargantuan meals, afternoon naps and round-the-clock medical supervision. However, the life is as degenerate as it is seductive — sickly, morbid and hermetically sealed from the wider world.

The decadence of the WEF is very different from the one skewered by Mann. The delegates to the WEF are hyperactive while the patients in the sanatorium are lethargic — the former rush from meeting to meeting rather than having five or six meals a day. They listen to worthy talks about problems and solutions by heads of governments, central bankers and star professors rather than, like Mann’s characters, sticking their heads in the sand.

However, there are profound similarities beneath the surface. There is the same quality of exhaustion in today’s world and that of Mann’s prewar Germany. For all of our obsessive

hyperactivity, never more clearly on display than among the masters of the universe on a mountain, we have run out of steam. Economies are stagnant, particularly in Europe. Culture is stuck on repeat — think of all those remakes and sequels. And there is the same disconnect between those gathered at Davos — whether delegates or sanitorium dwellers — and the rest of the world.

The WEF, however, does not offer anything that compares with the argument about the future of liberal society in The Magic Mountain.

In the book, Castorp falls in with two intellectuals who live in the village of Davos below his sanatorium: an Italian humanist called Lodovico Settembrini and a Jewish-born cosmopolitan called Leo Naphta who is drawn to the 1917 communist revolution and traditional Catholicism. The two men carry on a bitter argument about the relative merits of liberalism and illiberalism that touches on every question that mattered in prewar Europe: nationalism, individualism, fairness, tradition, war, peace, terrorism and so on.

Settembrini mechanically repeats the central tenets of liberalism but does not seem to realize that the world is a very different place from what it was in 1850. Naphta splutters with contempt. “The mystery and precept of our age is not liberation and development of the ego,” Naphta says. “What our age needs, what it demands, what it will create for itself, is — terror.” Naphta puts his dedication to terror into practice by “winning” his argument with Settembrini by challenging the humanist to a duel and blowing his own brains out, thereby celebrating his own dedication to terror and sending his antagonist into a self-lacerating depression.

This argument is as relevant today as it was when it was written. Settembrini is like the bulk of today’s liberals — well-meaning but incapable of recognizing that the world of their youth has changed beyond recognition. Naphta’s enthusiasm for mixing incompatible faiths that have nothing in common other than their antagonism to liberalism is all too familiar today, too: Thus we have progressives who side with terrorists and evangelical Christians who side with Trump. Our liberalism, like Settembrini’s, only seems to have any energy when it is driving opponents mad.

In The Magic Mountain, the illiberal madness finally ends with the outbreak of World War I. Castorp hears of “a vast murderousness” stirring on the flatlands below and decides to leave the sanitorium — much against the wishes of his leaching doctors — and rejoin history. In the last scene of the novel, he participates in an infantry attack and sings to himself “Der Lindenbaum” from Schubert’s song cycle Winterreise — the great Romantic premonition of Europe’s death wish.

The same sense of “vast murderousness” hangs over the world today. Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskiy delivered a speech designed to rally support for Ukraine’s resistance to Russia’s aggression. Delegates anxiously discussed events in the Middle East and China’s saber rattling over Taiwan. However, there is one optimistic difference between Mann’s novel and today’s Davos. Mann wrote his novel six years after the decadence he analyzed led to one of the greatest slaughters in human history. We still have time — just — to write a better ending to the story.

Adrian Wooldridge is the global business columnist for Bloomberg Opinion. A former writer at The Economist, he is the author of The Aristocracy of Talent: How Meritocracy Made the Modern World. This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Speaking at the Copenhagen Democracy Summit on May 13, former president Tsai Ing-wen (蔡英文) said that democracies must remain united and that “Taiwan’s security is essential to regional stability and to defending democratic values amid mounting authoritarianism.” Earlier that day, Tsai had met with a group of Danish parliamentarians led by Danish Parliament Speaker Pia Kjaersgaard, who has visited Taiwan many times, most recently in November last year, when she met with President William Lai (賴清德) at the Presidential Office. Kjaersgaard had told Lai: “I can assure you that ... you can count on us. You can count on our support

Denmark has consistently defended Greenland in light of US President Donald Trump’s interests and has provided unwavering support to Ukraine during its war with Russia. Denmark can be proud of its clear support for peoples’ democratic right to determine their own future. However, this democratic ideal completely falls apart when it comes to Taiwan — and it raises important questions about Denmark’s commitment to supporting democracies. Taiwan lives under daily military threats from China, which seeks to take over Taiwan, by force if necessary — an annexation that only a very small minority in Taiwan supports. Denmark has given China a

Many local news media over the past week have reported on Internet personality Holger Chen’s (陳之漢) first visit to China between Tuesday last week and yesterday, as remarks he made during a live stream have sparked wide discussions and strong criticism across the Taiwan Strait. Chen, better known as Kuan Chang (館長), is a former gang member turned fitness celebrity and businessman. He is known for his live streams, which are full of foul-mouthed and hypermasculine commentary. He had previously spoken out against the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and criticized Taiwanese who “enjoy the freedom in Taiwan, but want China’s money”

A high-school student surnamed Yang (楊) gained admissions to several prestigious medical schools recently. However, when Yang shared his “learning portfolio” on social media, he was caught exaggerating and even falsifying content, and his admissions were revoked. Now he has to take the “advanced subjects test” scheduled for next month. With his outstanding performance in the general scholastic ability test (GSAT), Yang successfully gained admissions to five prestigious medical schools. However, his university dreams have now been frustrated by the “flaws” in his learning portfolio. This is a wake-up call not only for students, but also teachers. Yang did make a big