So what exactly should we do when people consider extant art racist? In 2020, the Vermont Law School decided that the solution was to use acoustic tiles to cover a pair of murals. The US Court of Appeals recently rejected the claim by artist Samuel Kerson that the decision violated his rights under the 1990 Visual Artists Rights Act.

However, even if the court’s interpretation was correct and federal law does not protect a work from being covered, the ruling should not be the end of the matter, not at least for those who love art.

Let us go back to the beginning. In 1993, the school retained Kerson to paint the murals for a community room. Entitled The Underground Railroad, Vermont and the Fugitive Slave, the work was supposed to decry the horrors of human enslavement and laud those brave and lucky enough to escape. An admiring reviewer at the time described Kerson’s style as “heavily symbolic, with exaggerated human figures that burst with energy.”

Illustration: Constance Chou

The exaggerated figures are now the problem. In recent years, students and faculty alike have argued that the mural depicts black people as “Sambo-like” and “cartoonish,” the school posted signs to add context, but the objectors were unappeased. Finally, the murals were covered.

If the racist aspects of the work are so obvious, the law school should have rejected it in the first place. It is true that judgements of what is objectionable change, and as we have lately seen, they can change fast. Still, the error, if error there was, seems attributable to the buyer, not the seller. Did the administrators not ask for an early peek? Were there not preliminary sketches that would have allowed authorities to say “This isn’t quite what we had in mind”?

Hindsight, to be sure, is easy. I am not blaming Vermont Law School. I am suggesting that the fault does not lie with the artist alone — in which case perhaps the solution should also not be left to lie on the artist alone. There are other approaches available, less destructive to the idea of art itself.

Consider how Tate Britain responded to concerns about supposedly racist imagery in the enormous 1927 mural The Expedition in Pursuit of Rare Meats by Rex Whistler. Public dialogue being what it is, there was little audience for experts who argued that Whistler’s images of African children led on leashes (a tiny part of the work) were intended as a criticism of how the British Empire acquired its culinary delicacies. Small wonder that the museum ultimately decided to close the restaurant where the mural decorated the walls. Happily, the mural will not disappear. The plan is to reopen the room as an exhibit space where visitors can view the mural fully intact, together with a new work by Keith Piper.

Other pro-art routes exist. Faced with claims that images in a Will Rogers mural were racist, the Fort Worth Art Commission in Texas, with the consent of the local branch of US National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), announced in July that the mural would remain but that plaques would be added to provide context.

I understand the corner into which the Vermont Law School has backed itself. The solution chosen by Tate Britain — turning the room into an exhibition space — would have been expensive. The Fort Worth solution — leaving the murals in place with explanatory materials — the school has already tried.

However, what does the school’s solution say about the nature of art? Consider the response in 2020 when a group of museums that were supposed to host a Philip Guston retrospective announced a postponement until next year because some of the paintings depict members of the Ku Klux Klan wearing hoods. That Guston intended the images as critical of white America’s culpability in anti-black violence was beside the point. An open letter from 100 artists and writers protesting the delay argued that the museum directors “lack faith in the intelligence of their audience.” (A revised, expanded exhibition debuted last year.)

I get what the signatories were driving at. In his excellent 2001 book Pictures & Tears: A History of People Who Have Cried in Front of Paintings, the art historian James Elkins argues that we are losing the sense that art is supposed to evoke emotional responses. The fact that the emotions are not always happy ones would seem to be the point.

True, Kerson is not Picasso, but we should be fighting for art, not for famous art.

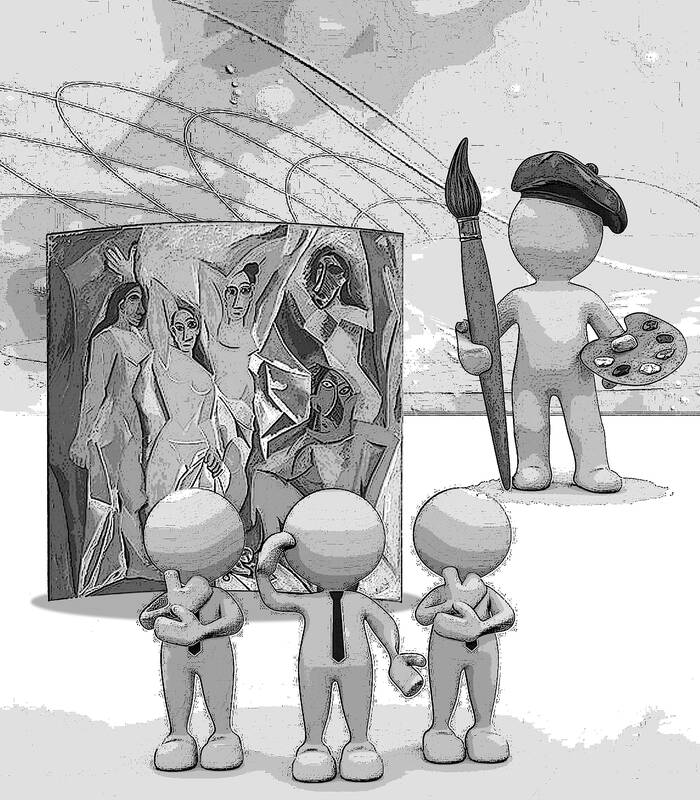

Speaking of Picasso, let us talk about Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, often considered the first genuinely cubist painting, an enormous canvas that hangs in Museum of Modern Art (MOMA) in New York. Most art critics rank the work as among Picasso’s greatest, but some describe the masterpiece as racist or exploitative. The painting portrays five prostitutes, two wearing African-style masks. (Some observers think that those two women, or perhaps all five, are meant to be black.)

Imagine now an upswing of online outrage by those who find the imagery racially offensive, and demand that the first cubist painting should be the next to go. Should MOMA take it down? Cover it with acoustic tiles? Or leave it on display, as now, with guidebooks and explanations? Even if I agreed with the critics, I would vote for the last; those who would prefer the first two do not get what art is for.

Stephen L. Carter is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist. A professor of law at Yale University, he is author, most recently, of Invisible: The Story of the Black Woman Lawyer Who Took Down America’s Most Powerful Mobster. This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Donald Trump’s return to the White House has offered Taiwan a paradoxical mix of reassurance and risk. Trump’s visceral hostility toward China could reinforce deterrence in the Taiwan Strait. Yet his disdain for alliances and penchant for transactional bargaining threaten to erode what Taiwan needs most: a reliable US commitment. Taiwan’s security depends less on US power than on US reliability, but Trump is undermining the latter. Deterrence without credibility is a hollow shield. Trump’s China policy in his second term has oscillated wildly between confrontation and conciliation. One day, he threatens Beijing with “massive” tariffs and calls China America’s “greatest geopolitical

Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) Chairwoman Cheng Li-wun (鄭麗文) made the astonishing assertion during an interview with Germany’s Deutsche Welle, published on Friday last week, that Russian President Vladimir Putin is not a dictator. She also essentially absolved Putin of blame for initiating the war in Ukraine. Commentators have since listed the reasons that Cheng’s assertion was not only absurd, but bordered on dangerous. Her claim is certainly absurd to the extent that there is no need to discuss the substance of it: It would be far more useful to assess what drove her to make the point and stick so

The central bank has launched a redesign of the New Taiwan dollar banknotes, prompting questions from Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) legislators — “Are we not promoting digital payments? Why spend NT$5 billion on a redesign?” Many assume that cash will disappear in the digital age, but they forget that it represents the ultimate trust in the system. Banknotes do not become obsolete, they do not crash, they cannot be frozen and they leave no record of transactions. They remain the cleanest means of exchange in a free society. In a fully digitized world, every purchase, donation and action leaves behind data.

A large majority of Taiwanese favor strengthening national defense and oppose unification with China, according to the results of a survey by the Mainland Affairs Council (MAC). In the poll, 81.8 percent of respondents disagreed with Beijing’s claim that “there is only one China and Taiwan is part of China,” MAC Deputy Minister Liang Wen-chieh (梁文傑) told a news conference on Thursday last week, adding that about 75 percent supported the creation of a “T-Dome” air defense system. President William Lai (賴清德) referred to such a system in his Double Ten National Day address, saying it would integrate air defenses into a