It is a good time to be in the air-conditioning business.

As my colleagues at Bloomberg News write, an additional 1 billion cooling units are expected to be installed by the end of the decade. It is one of the main ways in which humans are adapting to more frequent and intense heatwaves.

With a potentially strong El Nino on the horizon — a climate pattern that increases global temperatures — and greenhouse gas emissions still higher than ever, the world is facing another record-breaking summer, and another one, and another and so on.

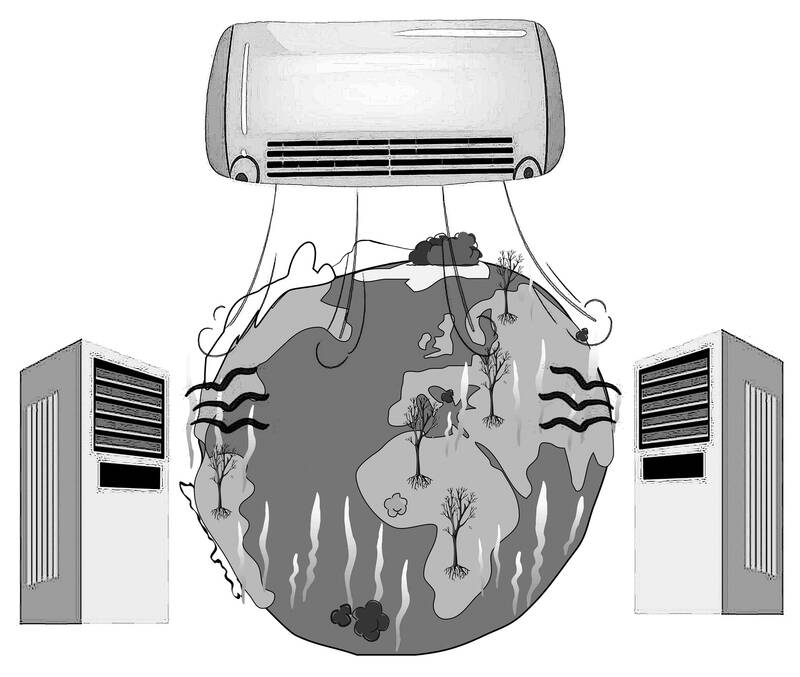

Illustration: Constance chou

For many, owning an air conditioner has become a matter of survival rather than comfort.

However, it creates a vicious cycle: The hotter the Earth gets, the more air conditioners people would need or want to install.

However, air conditioners are a disaster for the planet, containing toxic coolants with greater warming potential than carbon dioxide, and drawing on precious energy resources. So more air conditioners means more potential warming, which means more air conditioners.

While air conditioning has, no doubt, allowed humans to live in more extreme environments — just like heating at the other end of the temperature spectrum — new research shows that, just like other animals, humans are tied to a climate niche.

Going back millennia, this niche is the mean annual temperature (MAT) associated with the best conditions for humans to flourish.

An analysis of global population density gives us a peak MAT of about 13°C, and a second smaller peak at 27°C — associated with monsoon climates in South Asia.

These are the zones in which we thrive. The dip in the middle corresponds with drier climates that are not as suitable for us, our livestock or our crops; therefore, it has lower population densities, as seen in parts of the Middle East.

The temperature zone is no coincidence: GDP peaks at about 13°C, and if the temperature shifts, productivity falls.

For context, New York City and Milan have MATs of about 13°C.

The study, published in Nature, explores the human cost of rising global temperatures, taking a helicopter view on what works for people, and how climate change would alter that.

Policies and action put the world on track for 2.7°C of warming above pre-industrial temperatures by 2100. This would leave a staggering 2 billion people — 22 percent of the projected end-of-century population — exposed to unprecedented heat, defined as a MAT of 29°C and above.

India — set to be the world’s second-biggest market for cooling units after China by 2050 — and Nigeria would be the worst affected in terms of population, with a combined 900 million people living in dangerously hot temperatures.

Hundreds of millions of people would get pushed into the middle ground that has not historically supported dense human populations. That poses huge challenges for adaptation.

Air conditioning can help with the physiological effects of heat, and there are more climate-friendly ways of keeping cities cool with innovative construction and vegetation, but that is only part of the problem.

Given human reliance on plants and animals for food, which typically share human temperature preferences, and a plentiful water supply, exposure to such extreme heat would be existential for some areas — especially as the worst-hit areas are some of the poorest regions in the world and might not be able to afford to adapt.

“There will be parts of the world population that would be better off moving,” said Marten Scheffer, one of the study authors and an ecologist at Wageningen University and Research in the Netherlands.

Air conditioning is a poor band-aid for a huge systemic problem, and mass climate migration out of these areas is inevitable.

If the 2 billion estimate is accurate — bearing in mind that it does not account for sea-level change and other climate threats — that is a monumental challenge.

Migration events often lead to conflict and poor outcomes for refugees even at comparatively small magnitudes. A conversation about how to reaccommodate swathes of the global population while avoiding those problems has to start now.

The best way to keep humanity in its optimal climate niche would be to limit warming to the 1.5°C temperature target. Doing so, the study says, would mean a fivefold decrease in the population exposed to unprecedented heat. Every increment counts — for every 0.1°C of warming above 1.2°C, another 140 million people are exposed to dangerous heat.

Flip that on its head, Scheffer said, and there is a more positive message: For every 0.1°C of warming prevented, another 140 million people do not have to move away from their homes.

Here is to breaking the cycle — before entire regions become effectively uninhabitable.

Lara Williams is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering climate change. This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Every analyst watching Iran’s succession crisis is asking who would replace supreme leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei. Yet, the real question is whether China has learned enough from the Persian Gulf to survive a war over Taiwan. Beijing purchases roughly 90 percent of Iran’s exported crude — some 1.61 million barrels per day last year — and holds a US$400 billion, 25-year cooperation agreement binding it to Tehran’s stability. However, this is not simply the story of a patron protecting an investment. China has spent years engineering a sanctions-evasion architecture that was never really about Iran — it was about Taiwan. The

For Taiwan, the ongoing US and Israeli strikes on Iranian targets are a warning signal: When a major power stretches the boundaries of self-defense, smaller states feel the tremors first. Taiwan’s security rests on two pillars: US deterrence and the credibility of international law. The first deters coercion from China. The second legitimizes Taiwan’s place in the international community. One is material. The other is moral. Both are indispensable. Under the UN Charter, force is lawful only in response to an armed attack or with UN Security Council authorization. Even pre-emptive self-defense — long debated — requires a demonstrably imminent

Since being re-elected, US President Donald Trump has consistently taken concrete action to counter China and to safeguard the interests of the US and other democratic nations. The attacks on Iran, the earlier capture of deposed of Venezuelan president Nicolas Maduro and efforts to remove Chinese influence from the Panama Canal all demonstrate that, as tensions with Beijing intensify, Washington has adopted a hardline stance aimed at weakening its power. Iran and Venezuela are important allies and major oil suppliers of China, and the US has effectively decapitated both. The US has continuously strengthened its military presence in the Philippines. Japanese Prime

After “Operation Absolute Resolve” to capture former Venezuelan president Nicolas Maduro, the US joined Israel on Saturday last week in launching “Operation Epic Fury” to remove Iranian supreme leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei and his theocratic regime leadership team. The two blitzes are widely believed to be a prelude to US President Donald Trump changing the geopolitical landscape in the Indo-Pacific region, targeting China’s rise. In the National Security Strategic report released in December last year, the Trump administration made it clear that the US would focus on “restoring American pre-eminence in the Western hemisphere,” and “competing with China economically and militarily