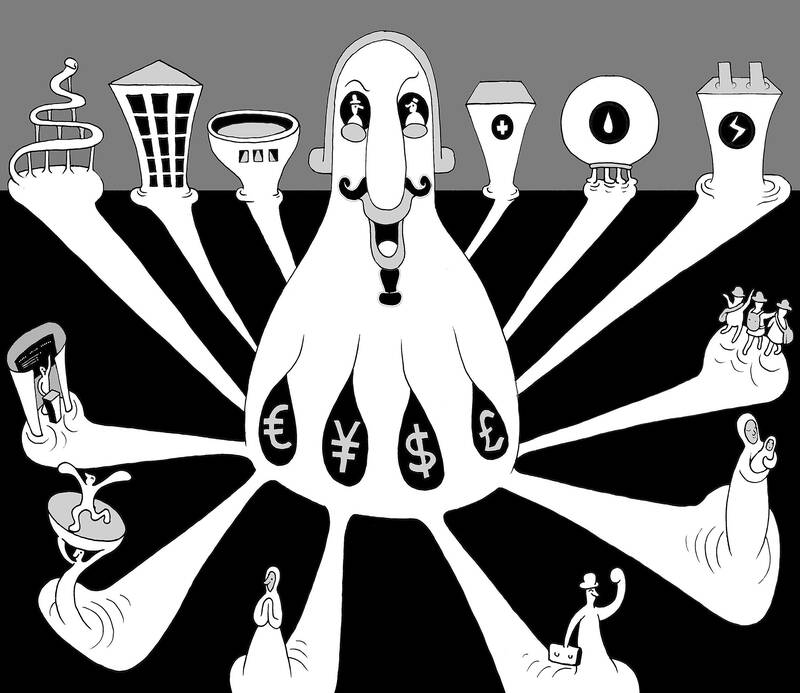

The key to economic development and ending poverty is investment. Nations achieve prosperity by investing in four priorities. Most important is investing in people, through quality education and healthcare. The next is infrastructure, such as electricity, safe water, digital networks and public transport. The third is natural capital, protecting nature. The fourth is business investment. The key is finance: mobilizing the funds to invest at the scale and speed required.

In principle, the world should operate as an interconnected system. Rich countries, with high levels of education, healthcare, infrastructure and business capital, should supply finance to poorer countries, which must urgently build up human, infrastructure, natural and business capital.

Money should flow from rich to poor countries. As emerging-market countries become richer, profits and interest would flow back to rich countries as returns on their investments.

Illustration: Mountain People

That is a win-win proposition. Rich and poor countries would benefit. Poor countries become richer, and rich countries earn higher returns than if they invested only in their own economies.

Strangely, international finance does not work that way. Rich countries invest mainly in rich economies. Poorer countries get only a trickle of funds, not enough to lift them out of poverty. The poorest half of the world — low-income and lower-middle-income countries — produces about US$10 trillion per year, while the richest half of the world — high-income and upper-middle-income countries — produces about US$90 trillion.

Financing from the richer half to the poorer half should be about US$2 trillion to US$3 trillion per year. In reality, it is a small fraction of that.

The problem is that investing in poorer countries seems too risky. This is true in the short run. Suppose that the government of a low-income country wants to borrow to fund public education. The economic returns to education are very high, but need 20 to 30 years to realize, as today’s children progress through 12 to 16 years of schooling and only then enter the labor market.

However, loans are often for only five years, and are denominated in US dollars rather than the national currency.

Suppose the country borrows US$2 billion today, due in five years. That would be fine if in five years, the government can refinance the US$2 billion with another five-year loan.

With five refinance loans, each for five years, debt repayments are delayed for 30 years, by which time the economy would have grown sufficiently to repay the debt without another loan.

However, at some point along the way, the country would likely find it difficult to refinance the debt. Perhaps a pandemic, a Wall Street banking crisis or election uncertainty would scare investors.

When the country tries to refinance the US$2 billion, it finds itself shut out from the financial market. Without enough money to hand, and no new loan, it defaults, and lands in the IMF emergency room.

Like most emergency rooms, what ensues is not pleasant to behold. The government slashes public spending, incurs social unrest and faces prolonged negotiations with foreign creditors. In short, the country is plunged into a deep financial, economic and social crisis.

Knowing this in advance, credit-rating agencies such as Moody’s Investors Service and S&P Global give the countries a low credit score, below “investment grade.”

As a result, poorer countries are unable to borrow long term. Governments need to invest for the long term, but short-term loans push governments to short-term thinking and investing.

Poor countries pay very high interest rates. While the US government pays less than 4 percent per year on 30-year borrowing, the government of a poor country often pays more than 10 percent on five-year loans.

The IMF advises the governments of poorer countries not to borrow very much. In effect, the IMF tells the government that it is better to forgo education — or electricity, safe water or paved roads — to avoid a debt crisis. That is tragic advice. It results in a poverty trap, rather than an escape from poverty.

The situation has become intolerable. The poorer half of the world is being told by the richer half: decarbonize your energy system; guarantee universal healthcare, education and access to digital services; protect your rainforests; ensure safe water and sanitation; and more.

However, they are somehow to do all of this with a trickle of five-year loans at 10 percent interest.

The problem is not with the global goals. These are within reach, but only if the investment flows are high enough. The problem is the lack of global solidarity. Poorer nations need 30-year loans at 4 percent, not five-year loans at more than 10 percent. They need much more financing.

Poorer countries are demanding an end to global financial apartheid.

There are two ways to accomplish this. The first is to expand about fivefold the financing by the World Bank and the regional development banks — such as the African Development Bank. Those banks can borrow at 30 years and about 4 percent, and on-lend to poorer countries on those favorable terms. Yet their operations are too small. For the banks to scale up, G20 countries — including the US, China and EU nations — need to put a lot more capital into those multilateral banks.

The second way is to fix the credit-rating system, the IMF’s debt advice and the financial management systems of the borrowing countries. The system needs to be reoriented toward long-term sustainable development.

If poorer countries can borrow for 30 years, rather than five years, they would not face financial crises in the meantime. With the right kind of long-term borrowing strategy, backed by more accurate credit ratings and better IMF advice, poorer countries would access much higher flows on much more favorable terms.

The major countries have four meetings on global finance this year: in Paris in June, Delhi in September, the UN in September and Dubai in November.

If big countries work together, they can solve this. That is their real job, rather than fighting endless, destructive and disastrous wars.

Jeffrey D. Sachs, a professor and director of the Center for Sustainable Development at Columbia University, is president of the UN Sustainable Development Solutions Network. The views expressed in this column are his own.

In the US’ National Security Strategy (NSS) report released last month, US President Donald Trump offered his interpretation of the Monroe Doctrine. The “Trump Corollary,” presented on page 15, is a distinctly aggressive rebranding of the more than 200-year-old foreign policy position. Beyond reasserting the sovereignty of the western hemisphere against foreign intervention, the document centers on energy and strategic assets, and attempts to redraw the map of the geopolitical landscape more broadly. It is clear that Trump no longer sees the western hemisphere as a peaceful backyard, but rather as the frontier of a new Cold War. In particular,

When it became clear that the world was entering a new era with a radical change in the US’ global stance in US President Donald Trump’s second term, many in Taiwan were concerned about what this meant for the nation’s defense against China. Instability and disruption are dangerous. Chaos introduces unknowns. There was a sense that the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) might have a point with its tendency not to trust the US. The world order is certainly changing, but concerns about the implications for Taiwan of this disruption left many blind to how the same forces might also weaken

As the new year dawns, Taiwan faces a range of external uncertainties that could impact the safety and prosperity of its people and reverberate in its politics. Here are a few key questions that could spill over into Taiwan in the year ahead. WILL THE AI BUBBLE POP? The global AI boom supported Taiwan’s significant economic expansion in 2025. Taiwan’s economy grew over 7 percent and set records for exports, imports, and trade surplus. There is a brewing debate among investors about whether the AI boom will carry forward into 2026. Skeptics warn that AI-led global equity markets are overvalued and overleveraged

Japanese Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi on Monday announced that she would dissolve parliament on Friday. Although the snap election on Feb. 8 might appear to be a domestic affair, it would have real implications for Taiwan and regional security. Whether the Takaichi-led coalition can advance a stronger security policy lies in not just gaining enough seats in parliament to pass legislation, but also in a public mandate to push forward reforms to upgrade the Japanese military. As one of Taiwan’s closest neighbors, a boost in Japan’s defense capabilities would serve as a strong deterrent to China in acting unilaterally in the