The Future of Life Institute’s open letter demanding a six-month precautionary pause on artificial-intelligence (AI) development has already been signed by thousands of high-profile figures, including Elon Musk. The signatories worry that AI labs are “locked in an out-of-control race” to develop and deploy increasingly powerful systems that no one – including their creators — can understand, predict or control.

What explains this outburst of panic among a certain cohort of elites? Control and regulation are obviously at the center of the story, but whose? During the proposed half-year pause when humanity can take stock of the risks, who will stand for humanity? Since AI labs in China, India and Russia will continue their work (perhaps in secret), a global public debate on the issue is inconceivable.

Still, we should consider what is at stake, here. In his 2015 book, Homo Deus, the historian Yuval Harari predicted that the most likely outcome of AI would be a radical division — much stronger than the class divide — within human society. Soon enough, biotechnology and computer algorithms would join their powers in producing “bodies, brains and minds,” resulting in a widening gap “between those who know how to engineer bodies and brains and those who do not.” In such a world, “those who ride the train of progress will acquire divine abilities of creation and destruction, while those left behind will face extinction.”

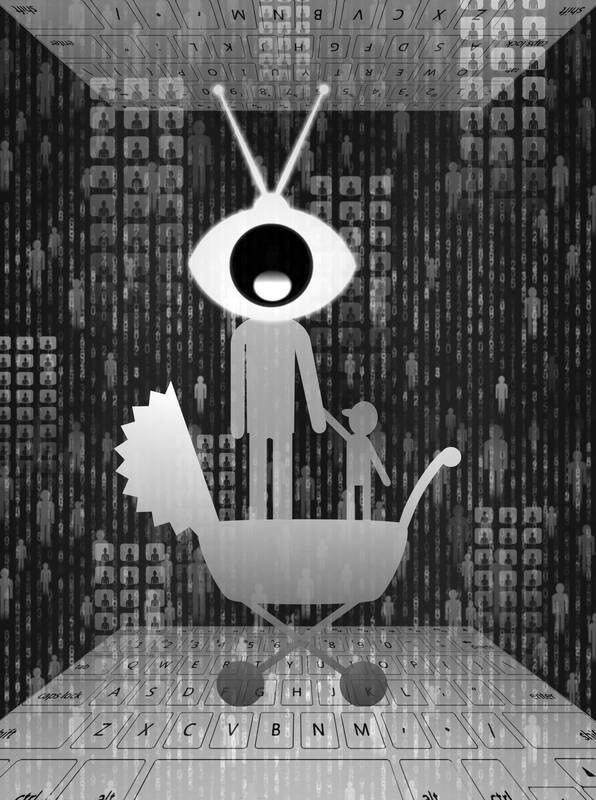

Illustration: Yusha

The panic reflected in the AI letter stems from the fear that even those who are on the “train of progress” will be unable to steer it. Our current digital feudal masters are scared. However, what they want is not public debate, but rather an agreement among governments and tech corporations to keep power where it belongs.

A massive expansion of AI capabilities is a serious threat to those in power — including those who develop, own and control AI. It points to nothing less than the end of capitalism as we know it, manifest in the prospect of a self-reproducing AI system that will need less and less input from human agents (algorithmic market trading is merely the first step in this direction). The choice left to us will be between a new form of communism and uncontrollable chaos.

OLD PARADOX

The new chatbots will offer many lonely (or not so lonely) people endless evenings of friendly dialogue about movies, books, cooking or politics. To reuse an old metaphor of mine, what people will get is the AI version of decaffeinated coffee or sugar-free soda: a friendly neighbor with no skeletons in its closet, an Other that will simply accommodate itself to your own needs.

There is a structure of fetishist disavowal here: “I know very well that I am not talking to a real person, but it feels as though I am — and without any of the accompanying risks.”

In any case, a close examination of the AI letter shows it to be yet another attempt at prohibiting the impossible. This is an old paradox: It is impossible for us, as humans, to participate in a post-human future, so we must prohibit its development.

To orient ourselves around these technologies, we should ask Lenin’s old question: Freedom for whom to do what? In what sense were we free before? Were we not already controlled much more than we realized? Instead of complaining about the threat to our freedom and dignity in the future, perhaps we should first consider what freedom means now. Until we do this, we will act like hysterics who, as French psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan said, are desperate for a master, but only one that we can dominate.

The futurist Ray Kurzweil predicted that, owing to the exponential nature of technological progress, we will soon be dealing with “spiritual” machines that will not only display all the signs of self-awareness, but also far surpass human intelligence.

However, one should not confuse this “post-human” stance for the paradigmatically modern preoccupation with achieving total technological domination over nature. What we are witnessing, instead, is a dialectical reversal of this process.

GOD OR DEVIL

Today’s “post-human” sciences are no longer about domination. Their credo is surprise: What kind of contingent, unplanned emergent properties might “black-box” AI models acquire for themselves? No one knows, and therein lies the thrill — or, indeed, the banality — of the entire enterprise.

Hence, earlier this century, the French philosopher-engineer Jean-Pierre Dupuy discerned in the new robotics, genetics, nanotechnology, artificial life and AI a strange inversion of the traditional anthropocentric arrogance that technology enables: “How are we to explain that science became such a ‘risky’ activity that, according to some top scientists, it poses today the principal threat to the survival of humanity? Some philosophers reply to this question by saying that Descartes’ dream — ‘to become master and possessor of nature’ — has turned wrong, and that we should urgently return to the ‘mastery of mastery.’ They have understood nothing. They don’t see that the technology profiling itself at our horizon through ‘convergence’ of all disciplines aims precisely at nonmastery. The engineer of tomorrow will not be a sorcerer’s apprentice because of his negligence or ignorance, but by choice.”

Humanity is creating its own god or devil. While the outcome cannot be predicted, one thing is certain. If something resembling “post-humanity” emerges as a collective fact, our worldview will lose all three of its defining, overlapping subjects: humanity, nature and divinity.

Our identity as humans can exist only against the background of impenetrable nature, but if life becomes something that can be fully manipulated by technology, it will lose its “natural” character. A fully controlled existence is one bereft of meaning, not to mention serendipity and wonder.

The same, of course, holds for any sense of the divine. The human experience of “god” has meaning only from the standpoint of human finitude and mortality. Once we become Homo deus and create properties that seem “supernatural” from our old human standpoint, “gods” as we knew them will disappear. The question is what, if anything, will be left. Will we worship the AIs that we created?

There is every reason to worry that tech-gnostic visions of a post-human world are ideological fantasies obfuscating the abyss that awaits us. Needless to say, it would take more than a six-month pause to ensure that humans do not become irrelevant, and their lives meaningless, in the not-too-distant future.

Slavoj Zizek, professor of philosophy at the European Graduate School, is international director of the Birkbeck Institute for the Humanities at the University of London and the author, most recently, of Heaven in Disorder.

Copyright: Project Syndicate

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) challenges and ignores the international rules-based order by violating Taiwanese airspace using a high-flying drone: This incident is a multi-layered challenge, including a lawfare challenge against the First Island Chain, the US, and the world. The People’s Liberation Army (PLA) defines lawfare as “controlling the enemy through the law or using the law to constrain the enemy.” Chen Yu-cheng (陳育正), an associate professor at the Graduate Institute of China Military Affairs Studies, at Taiwan’s Fu Hsing Kang College (National Defense University), argues the PLA uses lawfare to create a precedent and a new de facto legal

Chile has elected a new government that has the opportunity to take a fresh look at some key aspects of foreign economic policy, mainly a greater focus on Asia, including Taiwan. Still, in the great scheme of things, Chile is a small nation in Latin America, compared with giants such as Brazil and Mexico, or other major markets such as Colombia and Argentina. So why should Taiwan pay much attention to the new administration? Because the victory of Chilean president-elect Jose Antonio Kast, a right-of-center politician, can be seen as confirming that the continent is undergoing one of its periodic political shifts,

In the first year of his second term, US President Donald Trump continued to shake the foundations of the liberal international order to realize his “America first” policy. However, amid an atmosphere of uncertainty and unpredictability, the Trump administration brought some clarity to its policy toward Taiwan. As expected, bilateral trade emerged as a major priority for the new Trump administration. To secure a favorable trade deal with Taiwan, it adopted a two-pronged strategy: First, Trump accused Taiwan of “stealing” chip business from the US, indicating that if Taipei did not address Washington’s concerns in this strategic sector, it could revisit its Taiwan

Taiwan’s long-term care system has fallen into a structural paradox. Staffing shortages have led to a situation in which almost 20 percent of the about 110,000 beds in the care system are vacant, but new patient admissions remain closed. Although the government’s “Long-term Care 3.0” program has increased subsidies and sought to integrate medical and elderly care systems, strict staff-to-patient ratios, a narrow labor pipeline and rising inflation-driven costs have left many small to medium-sized care centers struggling. With nearly 20,000 beds forced to remain empty as a consequence, the issue is not isolated management failures, but a far more