Rene Magritte, one of Belgium’s most famous artists, was a leading member of a 1920s movement called surrealism, which sought revolution against the constraints of the rational mind.

When describing his paintings, Magritte said they “evoke mystery” and strived to ask beholders: “What does that mean? It does not mean anything, because mystery means nothing, it is unknowable.”

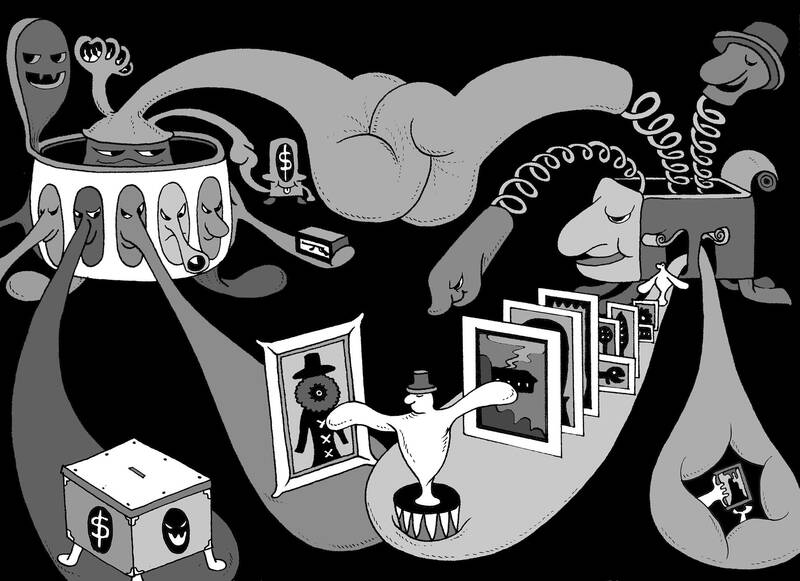

I sometimes feel as if I am looking at a Magritte painting when examining Russians’ ability to evade Western sanctions policies.

Illustration: Mountain People

Arkady Rotenberg, worth a reported US$3.5 billion, is a childhood friend of Russian President Vladimir Putin. He used to be Putin’s judo sparring partner, before progressing to become a rich businessman.

Rotenberg has publicly claimed to own the US$1 billion so-called “Putin’s Palace,” a huge Italianate complex on the Black Sea coast said to be secretly owned by the Russian president.

In March 2014, Rotenberg was one of the first Russians to be hit with sanctions after Russia unlawfully invaded Ukraine and annexed Crimea.

Yet two months after the restrictions were imposed, a complex web of shell companies linked to Rotenberg and his family was used to buy Magritte’s La Poitrine for US$7.5 million at a Sotheby’s auction in New York.

A US Senate investigation found that the painting was shipped to a storage facility in Germany called Hasenkamp, where it rested for five years. In August 2019, when a US congressional committee started investigating the purchase, the artwork was whisked off to Moscow.

In its report, the committee said the lack of banking regulations over art transactions was “shocking,” and created an “environment ripe for laundering money and evading sanctions.”

It directed sharp criticism at auction houses and art dealers for doing little to screen or stop sanctioned people from trading art.

Since the full-scale invasion of Ukraine last year, some additional measures have been taken.

Auction houses Christie’s, Sotheby’s and Bonhams canceled sales of Russian art in London in response to Western sanctions on the Kremlin and its wealthy cronies.

However, so much more could be done to tackle a notoriously opaque market that has been long favored by Russian oligarchs looking to shift money around. After all, paintings and sculptures are easier to transport and hide than yachts and private jets, many of which have been seized over the past year. Art also provides oligarchs with a mechanism to launder their reputations —weaving themselves into such a gilded world provides cultural, social and political standing.

The arrival of the Russian super-rich in the art world was announced in May 2008, when Roman Abramovich, then-owner of London-based soccer team Chelsea, bought Lucian Freud’s Benefits Supervisor Sleeping for US$7 million at Christie’s in New York. The next evening, he bought Francis Bacon’s Triptych for US$3 million from Sotheby’s.

This largesse came one week after Putin flipped from Russian president to prime minister, extending his power beyond the two consecutive terms allowed under the country’s constitution.

Leonid Mikhelson is the major shareholder in Novatek, a Russian gas company, and has done business with Gennady Timchenko, an oligarch who has been close to the Russian president for decades.

Mikhelson was one of several oligarchs summoned to the Kremlin the day after the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine last year. He has been sanctioned since 2014.

Yet during the same time period, Mikhelson’s foundation has also had a presence in London’s public art institutions, staging four shows at Whitechapel Gallery between 2014 and 2018.

Western allies of Kyiv seeking to put pressure on the Kremlin over the war crimes extravaganza unleashed on Ukraine could ban sanctioned Russians from their prestigious art markets, including auction houses. More stringent regulations about beneficial ownership could be introduced, which would help clean up the real-estate market, as well as the art world. An international task force should be established to recover priceless works of art looted from Ukrainian galleries and museums by Russian occupiers, and Western authorities should confiscate pieces bought by sanctioned individuals and their proxies.

The money should go toward the reconstruction of Ukraine.

The UK would not have to look far for such items. Two months after the war started last year, British authorities could have made a real statement.

The Victoria and Albert Museum hosted the blockbuster “Faberge: Romance to Revolution” exhibition displaying works that a Russian jeweler sold to the British royal family and aristocracy at the beginning of the 20th century. In prized place was the Rothschild Faberge clock egg from 1902, which includes a diamond-set cockerel popping out of the top every hour.

The Rothschild egg was bought at Christie’s in London in 2007 for £9 million (US$11.1 at the current exchange rate) by Russian businessman Alexander Ivanov. It was transferred to the Victoria and Albert Museum exhibition by Ivanov’s Hermitage Museum in St Petersburg, Russia, after receiving assurances from the UK that it would be exempt from seizure by the courts.

The egg was eventually returned to Russia months after Putin ordered his troops into a conflict in Ukraine that is increasingly defined by the deliberate targeting of civilians — in complete breach of all international laws.

Last week, the international criminal court in The Hague, Netherlands, indicted Putin for the mass abduction of Ukrainian children and issued a warrant for his arrest. Given the current situation, it is unlikely that Putin would ever risk visiting a country that would honor the arrest warrant.

However, another measure might have been taken to show the Russian president that the West means business.

Some time after Ivanov bought the Rothschild Faberge clock egg, he surprisingly decided to give it away.

The ownership was in 2015 transferred to a Russian individual who was hit by British, EU and US sanctions last year, when Russian tanks rolled into Ukraine. His name is Vladimir Putin.

Vladyslav Vlasiuk is a sanctions expert working in the Ukrainian presidential office.

US President Donald Trump and Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平) were born under the sign of Gemini. Geminis are known for their intelligence, creativity, adaptability and flexibility. It is unlikely, then, that the trade conflict between the US and China would escalate into a catastrophic collision. It is more probable that both sides would seek a way to de-escalate, paving the way for a Trump-Xi summit that allows the global economy some breathing room. Practically speaking, China and the US have vulnerabilities, and a prolonged trade war would be damaging for both. In the US, the electoral system means that public opinion

They did it again. For the whole world to see: an image of a Taiwan flag crushed by an industrial press, and the horrifying warning that “it’s closer than you think.” All with the seal of authenticity that only a reputable international media outlet can give. The Economist turned what looks like a pastiche of a poster for a grim horror movie into a truth everyone can digest, accept, and use to support exactly the opinion China wants you to have: It is over and done, Taiwan is doomed. Four years after inaccurately naming Taiwan the most dangerous place on

In their recent op-ed “Trump Should Rein In Taiwan” in Foreign Policy magazine, Christopher Chivvis and Stephen Wertheim argued that the US should pressure President William Lai (賴清德) to “tone it down” to de-escalate tensions in the Taiwan Strait — as if Taiwan’s words are more of a threat to peace than Beijing’s actions. It is an old argument dressed up in new concern: that Washington must rein in Taipei to avoid war. However, this narrative gets it backward. Taiwan is not the problem; China is. Calls for a so-called “grand bargain” with Beijing — where the US pressures Taiwan into concessions

Wherever one looks, the United States is ceding ground to China. From foreign aid to foreign trade, and from reorganizations to organizational guidance, the Trump administration has embarked on a stunning effort to hobble itself in grappling with what his own secretary of state calls “the most potent and dangerous near-peer adversary this nation has ever confronted.” The problems start at the Department of State. Secretary of State Marco Rubio has asserted that “it’s not normal for the world to simply have a unipolar power” and that the world has returned to multipolarity, with “multi-great powers in different parts of the