In coffee country, people do not need an extra shot to recognize their future is tough. On an iconic Indonesian island, powerful forces are eroding an industry that not only helped caffeinate the world, but provided livelihoods for generations and had a significant historical role as a template for economic development. It is not outlandish to contemplate Java without java.

Climate change has been central to the good times and instrumental to coffee’s discouraging prognosis in Indonesia, the world’s fourth-largest producer. Crop shortfalls around the globe drove an epic advance last year in the price of beans, a rally that has cooled in recent months along with retreats in commodity prices.

Folks along the coffee chain do not like the omens. The long-term challenges they describe are not limited to Indonesia. The travails are shared, to degrees, by Brazil, Vietnam and Colombia. Ultimately, they are likely to be felt by urbanites in New York, Tokyo, London or anywhere lattes and mocha are a staple of social and professional life — or just surviving a weekend with young kids.

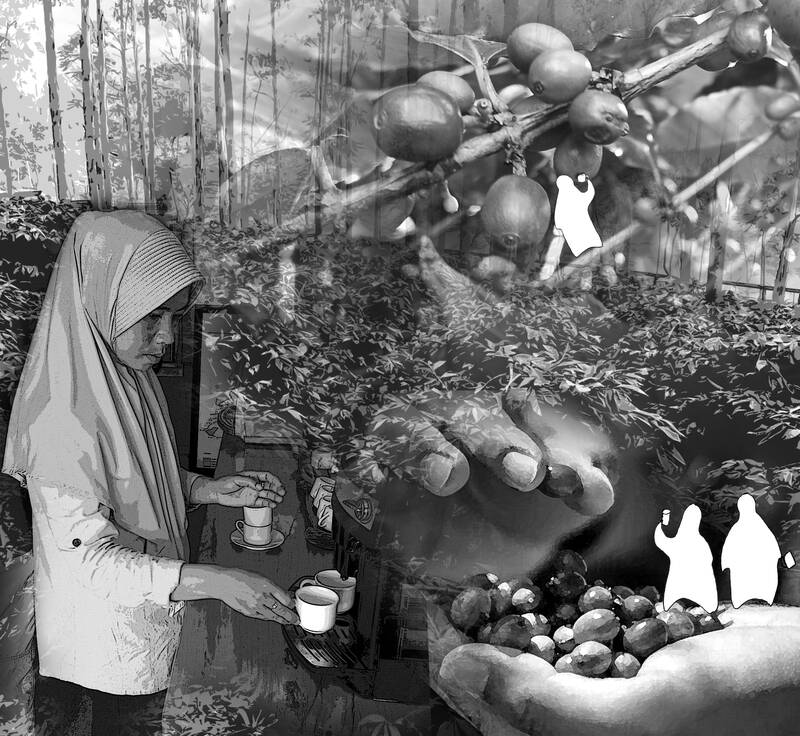

Illustration: Tania Chou

During a visit to the area around Banyuwangi in eastern Java, retailers and farmers shared their concerns — rising temperatures, unpredictable weather, inconsistent bean quality and deteriorating soil. A recent study said that land suitable for growing coffee would shrink dramatically by 2050, with the most highly suited regions declining by more than 50 percent as the planet warms.

Given the drink’s huge — and still growing — popularity, the math is punishing.

“Nearly every coffee production area on Earth is already experiencing increases in weather variability, which pose major threats to both plants and people,” according to a strategy document from World Coffee Research (WCR), an organization comprising coffee companies that was formed in 2012 to boost innovation.

An important part of the solution has to be the development of more climate-resistant varieties. However, this should not just be driven by industry. The nations with the most to lose — the majority are developing economies — need to recognize the importance not just to commerce, but social stability and the environment. It is one thing to say farmers should simply move to higher ground. Who buys the space for them? And what happens to communities already there?

AIR-CONDITIONED COMFORT

There are also laments that young Javanese are not interested in working the land, and instead prefer the air-conditioned comfort of offices a two-hour flight away in Jakarta, or choose to attend college in one of Indonesia’s large cities. They would rather be anywhere other than their rural homes. Given the diminishing prospects for the industry, it is a wonder that any young Javanese remain in coffee-growing country at all.

Adi Susiyanto is one who stayed. Fixing me a pour-over of the robusta variety late one morning, Adi, a barista at A roadside cafe called Sarine Kopi, told me he knows something is wrong. He has lived around Banyuwangi all his life and reckons that climate change is slowly but surely reshaping life in the area.

“The quality of the coffee used to be consistently good,” he said. “Now, it’s all up to the weather.”

Nurul Hidayah, a fifth-generation farmer, shares the foreboding as she tries to dry beans in her front yard.

“It rains for much longer nowadays,” she said.

Association of Indonesian Coffee Exporters and Industries chairman Irfan Anwar prefers to see the mug as half full. Sure, production in the country faces substantial threats, but it is a similar story in several countries.

The challenge of climate change is not unique to Indonesia, and demand is holding up in the meantime, he said.

“We are not looking for problems,” he added.

They are sure to find him, and his counterparts, nonetheless. Early projections of a bumper Brazilian crop next year are unlikely to materialize. The Latin American giant is facing the inverse of Indonesia’s affliction — rainfall that is significantly below the historical average. Brazil has also contended in recent years with heavy frosts that ravaged crops.

In Vietnam, harvests are disappointing and stockpiles are falling. Hanoi has gone so far as to warn cultivators desperate for an income against switching to durians.

WRITTEN IN HISTORY

Whatever fundamental changes are coming to coffee in Indonesia, do not be surprised if they presage broader implications. The beverage is intimately tied to the economic, social and political history of the country.

Coffee bushes and drinking arrived in the late 1600s through Dutch merchants, according to Jean Gelman Taylor’s Indonesia: Peoples and Histories. East India Company officials began planting seeds around the site of present-day Jakarta, giving plants to Javanese provincial chiefs who ordered farmers to harvest beans to pay taxes, she wrote.

Coffee became a fixture of early transportation and warehouse systems. Supplies and cultivation were managed to reflect and influence market trends in Amsterdam, the commercial center of the colonial power. An entire fiscal system and networks of patronage fashioned trends in rural migration, finance, diet and even the evolution of sex work.

The natural environment has wreaked havoc before. In the 19th century, a virus spread among coffee plants and prompted a shift from arabica beans to the tougher and more bitter tasting robusta variety. The bulk of Indonesia’s coffee today is robusta, although arabica, a smoother blend, can also be found on the hillsides around Banyuwangi, jostling for space with rubber, chili and potato plants. Rising temperatures suggest renewed vulnerability to disease.

WCR — whose members include Starbucks Corp, Tim Hortons and JDE Peet’s — is working with Indonesia, among other nations, to develop varieties that can shore up production over coming decades.

“It has to happen now,” WCR CEO Jennifer Vern Long said. “We couldn’t even wait another year.”

Under the breeding program, seeds with new genetic combinations are being shipped this month.

“Any of the seeds could be a winner,” she said.

The world has a vital stake in seeing coffee, as we have come to know it, survive. It is not just about agriculture or preserving some sepia-tinged version of rural life. Coffee is deeply ingrained in finance, politics and the social structure of 21st century society.

For Indonesia, it is more elemental than that. The big fiscal subject in Jakarta these days is an ambitious plan for a US$34 billion new capital city carved out of forest in eastern Borneo. Why is it not possible for a fraction of that sum to be set aside to bank on the future of a commodity that is older than the Republic of Indonesia itself?

The pressures were enough to make Hariyono, a farmer who like many Indonesians goes by one name, invest in history. He inherited the business from his father and thought seriously about giving up the caffeine game more than 10 years ago in favor of rearing goats.

After talking over his family’s legacy with his dad, Hariyono decided to add a working coffee museum to the site. When I called on him at Kampong Kopi Lego, preschoolers watched as staff melted beans in pans over fire pots.

Pouring us cups, Hariyono fretted about the rich heritage — good and ill — that stands to be lost. As vital as the weather is, there is more to it than rain or shine.

“The young don’t want to be coffee farmers, they don’t see the profit,” he said. “I want them to know a very basic fact, that we are one of the main producers in the world. That knowledge shouldn’t be lost. That’s my mission.”

Java sans its namesake drink? A distinct possibility, Hariyono says, although he tries to be optimistic.

“Maybe I am a little bit crazy,” he said.

Daniel Moss is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering Asian economies, and was previously executive editor of Bloomberg News for economics.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion ofthe editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Jan. 1 marks a decade since China repealed its one-child policy. Just 10 days before, Peng Peiyun (彭珮雲), who long oversaw the often-brutal enforcement of China’s family-planning rules, died at the age of 96, having never been held accountable for her actions. Obituaries praised Peng for being “reform-minded,” even though, in practice, she only perpetuated an utterly inhumane policy, whose consequences have barely begun to materialize. It was Vice Premier Chen Muhua (陳慕華) who first proposed the one-child policy in 1979, with the endorsement of China’s then-top leaders, Chen Yun (陳雲) and Deng Xiaoping (鄧小平), as a means of avoiding the

In the US’ National Security Strategy (NSS) report released last month, US President Donald Trump offered his interpretation of the Monroe Doctrine. The “Trump Corollary,” presented on page 15, is a distinctly aggressive rebranding of the more than 200-year-old foreign policy position. Beyond reasserting the sovereignty of the western hemisphere against foreign intervention, the document centers on energy and strategic assets, and attempts to redraw the map of the geopolitical landscape more broadly. It is clear that Trump no longer sees the western hemisphere as a peaceful backyard, but rather as the frontier of a new Cold War. In particular,

As the Chinese People’s Liberation Army (PLA) races toward its 2027 modernization goals, most analysts fixate on ship counts, missile ranges and artificial intelligence. Those metrics matter — but they obscure a deeper vulnerability. The true future of the PLA, and by extension Taiwan’s security, might hinge less on hardware than on whether the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) can preserve ideological loyalty inside its own armed forces. Iran’s 1979 revolution demonstrated how even a technologically advanced military can collapse when the social environment surrounding it shifts. That lesson has renewed relevance as fresh unrest shakes Iran today — and it should

The last foreign delegation Nicolas Maduro met before he went to bed Friday night (January 2) was led by China’s top Latin America diplomat. “I had a pleasant meeting with Qiu Xiaoqi (邱小琪), Special Envoy of President Xi Jinping (習近平),” Venezuela’s soon-to-be ex-president tweeted on Telegram, “and we reaffirmed our commitment to the strategic relationship that is progressing and strengthening in various areas for building a multipolar world of development and peace.” Judging by how minutely the Central Intelligence Agency was monitoring Maduro’s every move on Friday, President Trump himself was certainly aware of Maduro’s felicitations to his Chinese guest. Just