One of the most troubling problems of our time is why intellectual progress is stalling. Governments and corporations throw vast resources at knowledge-creation, and yet intellectual breakthroughs are getting rarer and innovations punier.

A 2011 study of US data on creativity and originality came to a devastating conclusion: “The results indicate creative thinking is declining over time among Americans of all ages, especially in kindergarten through third grade. The decline is steady and persistent.”

Commentators have suggested various explanations for why this is happening, from rising inequality to the sheer accumulation of knowledge. None of them is convincing.

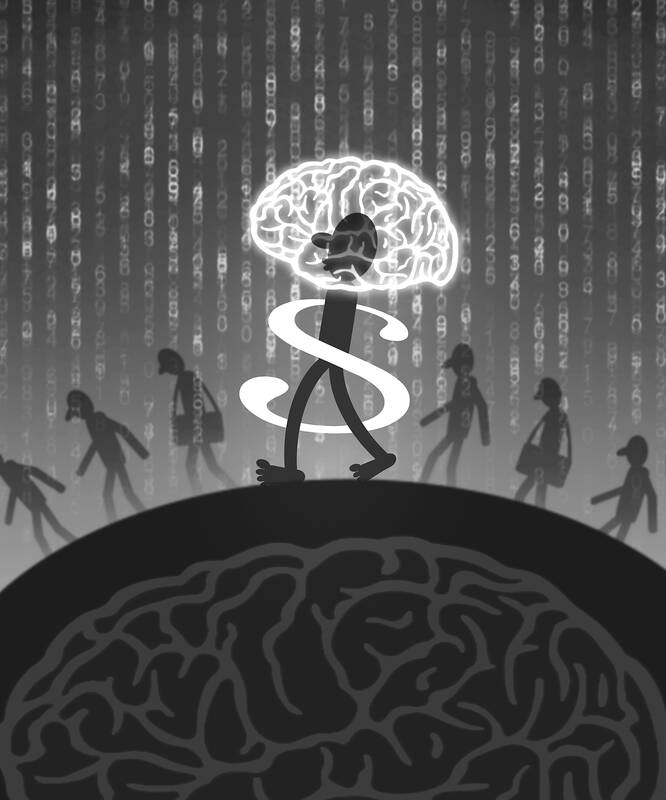

Illustration: Yusha

The late 19th century combined high degrees of inequality with extraordinary intellectual creativity, while the accumulation of knowledge surely provides ingenious people with more material to play with.

Here is a more straightforward explanation: We are not producing enough geniuses.

Geniuses are the driving force of intellectual and cultural progress. They come up with the great ideas that boost productivity and the great cultural creations that make life worth living. Societies that treat geniuses well — such as 15th-century Florence, in modern-day Italy, or 18th-century England — forge ahead. Societies that treat them badly, such 18th-century Spain or China under Mao Zedong (毛澤東), stagnate.

This is even more true in a knowledge-intensive society that depends on its ability to generate ideas rather than to produce things. Yet the modern world is increasingly falling into the latter category.

We like to think that we are better at cultivating and providing for geniuses than previous societies — we have constructed a universal school system to ensure that everybody can acquire the rudiments of education and a mass university system to push back the frontiers of knowledge.

Yet the educational system is doing a bad job of discovering and fostering geniuses. To start with, it misses potential stars from poorer backgrounds — a problem that economist Raj Chetty and his colleagues at Stanford University have dubbed the “lost Einstein” problem.

Top US universities are becoming finishing schools for the rich (modified by affirmative action for favored minorities) rather than intellectual powerhouses. Harvard University is typical of elite schools in that it takes more students from the top 2 percent of income earners than from the bottom 50 percent.

The geniuses who decide to make academia their home are then crushed under the weight of academic and administrative tedium, forced to crawl along the frontier of knowledge with a magnifying glass to get a doctorate and then obliged to publish whatever they can in learned journals if they want to get tenure. (They also have to steer clear of controversial subjects if they do not want their careers to go up in flames.)

If they get tenure, they are obliged to spend their most intellectually fertile years teaching basic courses, marking “quizzes” and dealing with missives from the ever-expanding army of bureaucrats that universities are hiring faster than they are hiring professors. If they fail to get tenure, they are condemned to become academic nomads, hopping from one-short term contract to another.

We have inadvertently produced a formula for genius destruction: Ignore the numerous Einsteins from the lower classes and then take the Einsteins that you do discover and turn them into drudges.

Premodern societies with rudimentary education systems certainly missed even more hidden Einsteins — or Jude the Obscures — but they might have done a better job at providing the geniuses they discovered with no-strings-attached billets. Kings and aristocrats furnished favored intellectuals with comfortable sinecures. Frederick II, king of Denmark and Norway from 1559 to 1588, provided astronomer Tycho Brahe with a guaranteed income for life, a 800-hectare island and enough additional money to build a uraniborg, or heavenly castle, to act as a home and an observatory.

Newcomers, such as the Medicis in Florence, established themselves on the social scene by acting as even greater friends to geniuses than blue bloods.

Churches provided favored intellectuals with perches that combined comfortable livings with minimum requirements. Anglo-Irish author Jonathan Swift wrote his masterpieces while he was a dean of St Patrick’s Cathedral in Dublin.

From the early 19th century onward, colleges at the University of Oxford and the University of Cambridge offered prize or examination fellowships to brilliant young academics without even imposing the obligation of residence.

This genius-first attitude survived well into the 20th century: Cambridge gave Austrian philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein a professorship even though he published little, and refused to do any administration or teach anybody but a few chosen students. It is impossible to imagine him getting tenure today.

There have been several innovative attempts to deal with the growing genius problem, particularly in the US. In 1933, Harvard created a Society of Fellows to provide its most brilliant graduate students with a chance to escape from the doctorate grind and give them the freedom to think — “freedom from Harvard at Harvard” in the words of one of its beneficiaries, Edward Tenner.

In 1981, the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation introduced “genius awards,” which provided 20 to 30 outstanding individuals with no-strings-attached payments (currently US$800,000 over five years) so that they can devote themselves to their work.

In 2011, tech billionaire Peter Thiel invented “stop out” grants whereby 20 to 25 high-school graduates are paid to delay going to university for a couple of years and instead focus on starting a business, doing independent research or solving a social problem.

These ideas have all had a positive impact.

Harvard fellows include such intellectual luminaries as psychologist B.F. Skinner and linguist Noam Chomsky. MacArthur award winners are objects of jealousy and awe across the US elite. The combined market capitalization of firms created by Thiel fellows is already more than US$45 billion.

Yet they are necessarily confined to a miniscule number of people — in Harvard’s case, to the elite within the Harvard elite and in the MacArthur award case to a wider, but still narrow credentialed (and usually liberal) elite. They are also vulnerable to the subjective bias of the awarders, whether they are liberal in the MacArthur case or libertarian-conservative in the Thiel one.

It is time to think much bigger. Why not provide a universal basic income (UBI) for all geniuses so that they have an opportunity to devote their lives to pure thought undisturbed by the humdrum concerns of daily life?

This idea was floated in an intriguing sub-stack called “Ideas Sleep Furiously,” but could do with a much wider discussion.

UBI for geniuses might work something like this: Schoolchildren would be given a succession of IQ tests during their school years. IQ tests because they are the best method we have of assessing raw intellectual ability rather than school learning. A succession because everybody can have an off day — physicist Richard Feynman liked telling people that he had scored only 124 in an IQ test.

Children who score 145 or higher would then be offered a life-long genius award. These awards would not need to be lavish — just enough so that geniuses could afford to live a middle-class lifestyle.

They could start at, say, US$75,000 a year and go up by US$25,000 increments every decade. The payments could expire if our geniuses decided to take paid employment, but then resume if they decided to “drop out” again.

There are some obvious objections to the idea. One is that not all people with high IQs would turn out to be geniuses because geniuses also need certain personality traits such as grit and focus.

However, this is only half-true. Having a high IQ is necessary if not a sufficient condition for high levels of cognitive achievement. They are also positively correlated with other desirable cognitive traits such as focus and endurance.

Given the relative simplicity of testing for IQ and the clear harm that is imposed in allocating rare talent to humdrum jobs, paying genius awards to a few non-geniuses seems like a reasonable cost.

A second objection is that UBI for geniuses would simply reward people who have already won a winning lottery ticket in life. The compassionate answer to this objection is that many geniuses find it hard to relate to the wider society. They are too preoccupied by intellectual puzzles (astronomer Isaac Newton went into such deep trances that he would forget to eat) or too introverted to talk to others (Paul Dirac, one of the pioneers of quantum physics, spoke so little that his colleagues at Cambridge invented a unit called the “Dirac,” or one word per hour).

“Great wits are sure to madness near allied. And thin partitions do their bounds divide,” as poet John Dryden put it.

UBI will clearly be good for the geniuses themselves, and those who do not need it can renounce it by getting a job.

However, the same can be said about other troubled groups (San Francisco is introducing UBI for transgender people, for example).

The more compelling answer is that UBI for geniuses will massively benefit society as a whole. UBI is good for us, as well as them.

Psychologist Heiner Rindermann and his collaborators have taken three widely used international tests — from the Programme for International Student Assessment, the Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study and the Progress in International Reading Literacy Study — and converted their scores into a single “cognitive ability score” for almost 100 countries. They demonstrated not only that countries with higher average IQ scores are richer than the rest, but also that the top 5 percent have the biggest impact on overall wealth.

If you want to improve the lot of the average Joe, then the best way to do it is to treat the brightest well.

UBI for geniuses would promote equality of opportunity in three ways: by introducing universal testing in schools, and thereby discovering more hidden high achievers; by giving all students, but particularly the poor, for whom a guaranteed income means more than for the rich, an incentive to do well academically; and by demonstrating that there is a root to success other than sport and pop music.

A 2016 paper by economists David Card and Laura Giuliano demonstrated that the introduction of universal screening in a large Florida school district led to a substantial increase in the fraction of poor and minority children who were put into gifted education programs. The percentage of non-Hispanic African Americans rose from 12 percent to 17 percent and of Hispanics from 16 percent to 27 percent, while the percentage of whites fell from 61 percent to 43 percent.

UBI for geniuses would do more for the US’ stalled upward mobility than anything since the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act, also known as “GI Bill,” after World War II.

UBI for geniuses might also provide an instrument for leveling up, between and within countries.

In his new book, The Culture Transplant: How Migrants Make the Economies They Move to a Lot Like the Ones They Left, economist Garett Jones writes that just seven countries out of nearly 200 (the US, China, Japan, South Korea, France, Germany and the UK) are responsible for the vast majority of the world’s patents, research grants, scientific publications patents and Nobel prizes.

The others could catch up with these “idea treasuries” by introducing UBI for their native-born geniuses or, more boldly still, offering no-strings-attached genius grants to high-IQ foreigners who are willing to relocate.

Likewise, the lion’s share of advanced intellectual work in the US takes place in a handful of knowledge clusters. If the US government makes the mistake of rejecting the UBI for geniuses idea, then ambitious states outside the magic circle could seize on it instead to improve their long-term prospects.

In the wake of musician Christine McVie’s death on Nov. 30, we have been repeatedly reminded of her 1977 song Don’t Stop (Thinking About Tomorrow) with its cheerful assurance that “it’ll be here better than before.”

Former US president Bill Clinton made the song the unofficial theme tune of his administration.

However, since that administration ended, “tomorrow” has lost much of its promise. In the West, large majorities of parents expect their children to be worse off than them. Across the world, people are terrified by the seemingly insoluble problem of global warming.

There is no better way to restore our faith in the future than to increase the amount of brainpower available to humankind. And there is no easier way to increase that brainpower than to provide geniuses with the wherewithal to devote their lives to doing what only they can do: thinking thoughts that have never been thought before and solving problems that have hitherto been deemed insoluble.

Adrian Wooldridge is the global business columnist for Bloomberg Opinion. He is a former writer at The Economist.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

US President Donald Trump and Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平) were born under the sign of Gemini. Geminis are known for their intelligence, creativity, adaptability and flexibility. It is unlikely, then, that the trade conflict between the US and China would escalate into a catastrophic collision. It is more probable that both sides would seek a way to de-escalate, paving the way for a Trump-Xi summit that allows the global economy some breathing room. Practically speaking, China and the US have vulnerabilities, and a prolonged trade war would be damaging for both. In the US, the electoral system means that public opinion

They did it again. For the whole world to see: an image of a Taiwan flag crushed by an industrial press, and the horrifying warning that “it’s closer than you think.” All with the seal of authenticity that only a reputable international media outlet can give. The Economist turned what looks like a pastiche of a poster for a grim horror movie into a truth everyone can digest, accept, and use to support exactly the opinion China wants you to have: It is over and done, Taiwan is doomed. Four years after inaccurately naming Taiwan the most dangerous place on

In their recent op-ed “Trump Should Rein In Taiwan” in Foreign Policy magazine, Christopher Chivvis and Stephen Wertheim argued that the US should pressure President William Lai (賴清德) to “tone it down” to de-escalate tensions in the Taiwan Strait — as if Taiwan’s words are more of a threat to peace than Beijing’s actions. It is an old argument dressed up in new concern: that Washington must rein in Taipei to avoid war. However, this narrative gets it backward. Taiwan is not the problem; China is. Calls for a so-called “grand bargain” with Beijing — where the US pressures Taiwan into concessions

Wherever one looks, the United States is ceding ground to China. From foreign aid to foreign trade, and from reorganizations to organizational guidance, the Trump administration has embarked on a stunning effort to hobble itself in grappling with what his own secretary of state calls “the most potent and dangerous near-peer adversary this nation has ever confronted.” The problems start at the Department of State. Secretary of State Marco Rubio has asserted that “it’s not normal for the world to simply have a unipolar power” and that the world has returned to multipolarity, with “multi-great powers in different parts of the